Short Story Month: Guest Post from Denise Lewis Patrick: My Never-ending Stories

I have about a dozen spiral notebooks dating back to when I was fourteen years old. Their covers are elaborately decorated with drawings, doodles and graffiti-type pen scrawls. Inside are some very earnest poems, the titles of favorite songs from back-in-the-day (Aretha Franklin and the Jackson Five were repeats), and a few notes of encouragement from close friends. But the rest of the pages? They’re filled with unfinished short stories.

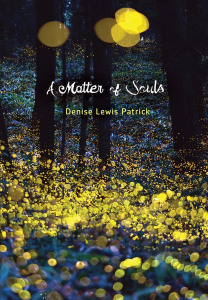

Carolrhoda LAB, April 2014.

I re-read my old poems all the time. So, I thought recently: if I can learn from my poetry, if I can see the beginnings of my writing voice and style in poems, maybe looking more closely at my early short story attempts would be illuminating. I pulled Volume One out of storage and opened it. Questions popped into my head before I could read a line: Why so many stunted efforts? Why could I finish poems, but not stories? Is there anything of my writing self today that’s recognizable?

Honestly, the experience of actually reading the seventeen starts and fragments was as fascinating as looking through a shoebox of old black and white photos.

First, I was clearly not bound by the adage to “write what you know.” Although most of my physical settings were vague—probably because I hadn’t really traveled much—the locales of the scenes did somehow feel distinctly different. Two stories were clearly set in huge mansions, complete with servants. Others gave the impression of urban or city backgrounds, nothing like my own small town, and one place could have been West Texas or New Mexico or Oklahoma. There was unexpected variety in other areas, too.

I was raised among schoolteachers, preachers, manual laborers and maids, yet the occupations of my characters ranged from firefighter to news reporter, fine artist to shop owner to slave and overseer. That last one did have a connection to the complex history of the Southern United States. But then, as now, I was not content to restrain my storytelling to my own personal environment. These days I might just as well set a story in New York as on another planet.

Only one of the early stories had a teenage main character. The rest were an assortment of young adults and parents involved in tangled relationships. Curiously, a recurring theme in my current fiction is the relationship between parents and their children of all ages. What became obvious as I turned the pages of my first notebook was that I love developing characters and having them play off of each other in real ways.

Quite a few stories turned on the intricacies of romantic relationships. I’d had crushes, of course, but had not experienced anything like love, or even young love back then. What I’d observed of adult relationships was limited, and my parents’ easy interactions and solid marriage didn’t give me any view of what troubles males and females run into when they try to partner up. So I guess I had a severe lack of confidence in my ability to actually portray that in a realistic way. None of those stories ever ended.

What comes through in my young writing is my attention to details and description. What I lacked in creating larger settings I made up for in minutiae. I was using gestures and description long before I learned how important they are to story.

“Sybil’s eyes pierced Georgia’s. She moved her hand over the pearls on her throat.”

“Anthony kicked the dust, watching a little cloud form and float away.”

“She ran her hand through her short brown hair. David was on that bus. She was sure. Positive.”

Nice lines for an amateur, I think. Almost, but not quite, the type of line I might write today. So the young me was clearly feeling out the strategies and tools that I later used to build story with: Characters. Gestures. Detail. What I didn’t get a grip on was faith in my own growing abilities.

For many years after college, I did not write stories. Maybe I was afraid—especially of all the hungry, unfulfilled notebooks that I left at my parents’ home when I moved away. I kept writing poetry. Through writing poetry I began to understand the power of being more concise, of honing meaning by finding the best, most right words.

And one day, nearly 30 years after I began it, I found one of those old stories torn from a later notebook. This one was nearly complete, a story about plain parents who sacrifice to give their only daughter a fancy education; about a father who loves his daughter, but can’t bring himself to tell her. About a daughter, who feels she’s failed her parents, but can’t find the voice to tell them. By the time I read that handwritten draft, I’d become a parent myself.

I had added the dimension of time lived to gesture and character and dialogue in my writing repertoire. I had the courage not to be embarrassed by my limitations. I had a laptop. By then I’d learned that complete is not the same as end; that sometimes real life has no closure. I finished the story, and I’ve gone on to write many new ones.

Denise Lewis Patrick.

Denise Lewis Patrick, a Louisiana native transplanted to New Jersey, has written everything from poetry to puzzles to exhibit text for Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad Museum. She’s had more than two-dozen books published for children, from picture books to middle grade historical novels THE ADVENTURES OF MIDNIGHT SON and THE LONGEST RIDE She’s also author of three books for American Girl’s New Orleans historical character, Cécile Rey. She’s a mom of four, and an adjunct writing professor. Her most current book is A MATTER OF SOULS, a collection of young adult short stories published by Carolrhoda Lab in April.