The Old West Was a Different Country

Here’s my confession.

I don’t set my novels in the Old West.

I don’t set my novels in the Old West.

They’re set in Robbville; a place that looks and sounds like the 21st century’s version of the Old West, plus a lot of facts and a blast of my creative imagination; such as it is.

But it’s not the real Old West.

That’s because recreating any society is impossible. Societies are built from thousands of details that cannot be crammed into a novel.

In the Old West, for instance, people joked differently, used different slang, handled different objects, experienced different politics.

Here are a very few examples: Jokes in 19th Century America were corny beyond belief because society was corny.

People indulged in sex and coarse behavior in private (of course), but they never talked about it in public, and they never wrote about it in books, magazines or newspapers. And “nice” people didn’t curse around other nice people.

Hence jokes like this one. “How do you make a Maltese cross? By stepping on his tail.” Ha ha.

“How do you make a Maltese cross? By stepping on his tail.” Ha ha.

Names were different. More than half of all men used the initials for their first and middle names to identify themselves, and nicknames were much more common in the West than in the East.

Those names included Cattle Kate, Black Jack Ketchum, Dutch Henry, Billy the Kid, Calamity Jane, Texas John Slaughter, Pawnee Bill, Bittercreek Newcomb, etc.

Language itself was different.

Ron Scheer, at http://buddiesinthesaddle.blogspot.com, collects and publishes words used by 19th century Americans, particularly in the West, and here are a few of those words and where he got them.

Black-and-tan = derogatory term for someone of mixed race.

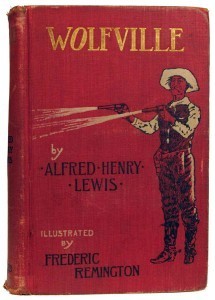

“The way he gets a bullet onder that black-an’-tan’s left wing don’t worry him a little bit.” Alfred Henry Lewis, Wolfville.

“The way he gets a bullet onder that black-an’-tan’s left wing don’t worry him a little bit.” Alfred Henry Lewis, Wolfville.

Last run of shad = having a very thin, wretched, forlorn, or played-out appearance.

“I don’t think I could accuse him of being personal—I look like ‘the last run o’ shad.’” G. Frank Lydston, Poker Jim, Gentleman.

Flannel-mouthed = slow talking; loud; boasting; characterized by deceptive speech.

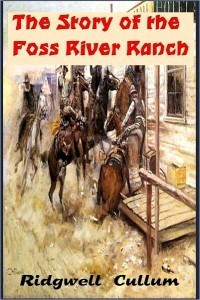

“You ask for dirty work to be done, an’ when that dirty work’s done, gorl-darn-it you croak like a flannel-mouthed temperance lecturer.” Ridgwell Cullum, The Story of the Foss River Ranch.

“You ask for dirty work to be done, an’ when that dirty work’s done, gorl-darn-it you croak like a flannel-mouthed temperance lecturer.” Ridgwell Cullum, The Story of the Foss River Ranch.

Deadfall = a rough saloon.

“Beware the pine tree’s withered branch, / Beware a ‘deadfall’, called Chalk Ranch.” William De Vere, Jim Marshall’s New Pianner.

When people traveled by train they said they were taking “the cars.”

Physical stuff was different for Americans in general.

A hair wreath was a decorative wreath made from the hair of dead and/or living people. Hair wreaths were considered memorials.

Hair wreath

Headlines blared scandal then as now, but the scandals were different.

Ulysses S. Grant was elected president in 1868.

Shortly thereafter, people began talking about the “Black Friday” scandal which involved Grant’s brother-in-law.

It was a scheme to control the gold market. When the plot failed, it almost shattered the nation’s economy.

(The more things change, etc.)

The Whiskey Ring scandal involved Grant’s own personal secretary. The secretary, politicians, government agents, whiskey distillers and distributors, diverted liquor tax money to their personal bank accounts.

By Howard Terpning. Among the Spirit People

Americans fought among themselves politically in the 19th century, just like they do now; but over different issues.

Women campaigned for temperance, an issue they won in the 20th century when Congress passed the prohibition laws.

Elites in the East defended America’s tribal peoples and fought for their rights–much like Civil Rights’ activists worked for African-Americans in the 1960s’–while Westerners derisively called Indians “Lo,” short for the phrase, “Lo, the poor Indian.”

You can guess the difference in Easterner and Western attitudes.

Finally, no writer can replicate the silence. That deep silence, which covered 99.5 percent of the West, was something many western adventurers mentioned in memoirs, letters and diaries.

Enigmatic Long House, by Curt Walters.

It awed them. It seemed to make pioneers, soldiers, tribal peoples, explorers, cowboys and every other person who ventured into the wilderness, feel something mysterious, something powerful they could not explain.

Reading non-fiction histories is the best bet for visiting the West as it really was.

Here’s a list of some non-fiction books I’ve found helpful.

Author Pete Cozzens is an American treasure. Especially useful are his The Struggle for Apacheria, volume one of Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars 1865-1890 and Conquering the Southern Plains, Volume 3, Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars 1865-1890. Or you can buy an abridged volume simply titled, “Eyewitnesses to The Indian Wars: 1865-1890.”

You can take “Eyewitnesses” literally. Cozzens collected eyewitness accounts for these books and they are thrilling.

On the Border With Crook, by Capt. John G. Bourke, Fourth Cavalry, is the best frontier memoir ever written.

Bourke served in Arizona against the Apache and in Montana and the Dakotas against the Sioux and Cheyenne.

Bourke was an interesting man who expressed a great deal of sympathy for tribal peoples.

After he retired from the Army, Bourke became a noted anthropologist.

Here’s another good one, Six Years with the Texas Rangers by James Gillette. Rooting, tooting.

And if you must read some fiction about the West (beside my books), choose The Wonderful Country, by Tom Lea, Adobe Walls, by W.R. Burnett, My Antonia, by Willa Cather and The Color of Lightning, by Paulette Jiles.

It’s true you can’t completely recreate a time and place, but these authors came close.

The post The Old West Was a Different Country appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.