Bliki: UnitTest

Unit testing is often talked about in software development, and

is a term that I've been familiar with during my whole time writing

programs. Like most software development terminology, however, it's

very ill-defined, and I see confusion can often occur when people

think that it's more tightly defined than it actually is.

Although I'd done plenty of unit testing before, my definitive

exposure was when I started working with Kent Beck and used the Xunit

family of unit testing tools. (Indeed I sometimes think a good term

for this style of testing might be "xunit testing.") Unit testing

also became a signature activity of ExtremeProgramming (XP), and led

quickly to TestDrivenDevelopment.

There were definitional concerns about XP's use

of unit testing right from the early days. I have a distinct memory

of a discussion on a usenet discussion group where us XPers were

berated by a testing expert for misusing the term "unit test." We

asked him for his definition and he replied with something like "in

the morning of my training course I cover 24 different definitions of

unit test."

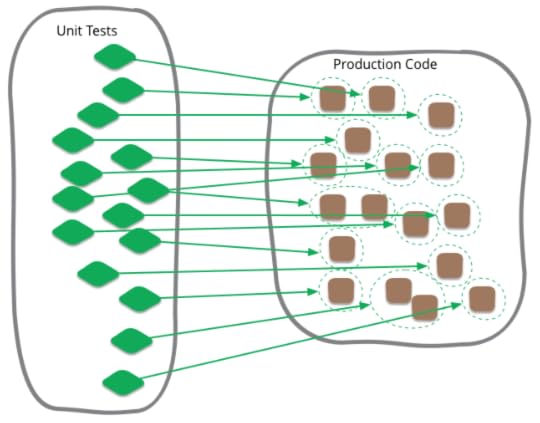

Despite the variations, there are some common elements. Firstly

there is a notion that unit tests are low-level, focusing on a small

part of the software system. Secondly unit tests are usually written

these days by the programmers themselves using their regular tools -

the only difference being the use of some sort of unit testing

framework [1]. Thirdly unit tests are

expected to be significantly faster than other kinds of tests.

So there's some common elements, but there are also differences.

One difference is what people consider to be a unit.

Object-oriented design tends to treat a class as the unit,

procedural or functional approaches might consider a single function

as a unit. But really it's a situational thing - the team decides

what makes sense to be a unit for the purposes of their

understanding of the system and its testing. Although I start with

the notion of the unit being a class, I often take a bunch of

closely related classes and treat them as a single unit. Rarely I

might take a subset of methods in a class as a unit. However you

define it doesn't really matter.

Isolation

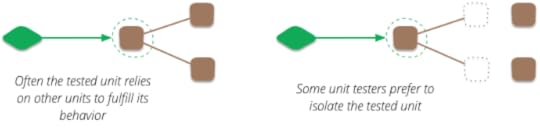

A more important distinction is whether the unit you're testing

should be isolated from its collaborators. Imagine you're testing an

order class's price method. The price method needs to invoke some

functions on the product and customer classes. If you follow the

principle of collaborator isolation you don't want to use the real

product or customer classes here, because a fault in the customer

class would cause the order class's tests to fail. Instead you use

TestDoubles for the collaborators.

But not all unit testers use this isolation. Indeed when xunit

testing began in the 90's we made no attempt to isolate unless

communicating with the collaborators was awkward (such as a remote

credit card verification system). We didn't find it difficult to

track down the actual fault, even if it caused neighboring tests

to fail. So we felt isolation wasn't an issue in practice.

Indeed this lack of isolation was one of

the reasons we were criticized for our use of the term "unit

testing". I think that the term "unit testing" is appropriate because

these tests are tests of the behavior of a single unit. We write

the tests assuming everything other than that unit is working

correctly.

As xunit testing became more popular in the 2000's the notion of

isolation came back, at least for some people. We saw the rise of

Mock Objects and frameworks to support mocking. Two schools of

xunit testing developed, which I call the classic and mockist

styles. Classic xunit testers don't worry about isolation but

mockists do. Today I know and respect xunit testers of both styles

(personally I've stayed with classic style).

Even a classic tester like myself uses test doubles when there's an

awkward collaboration. They are invaluable to remove

non-determinism

when talking to remote services. Indeed some classicist xunit testers

also argue that any collaboration with external resources, such as

a database or filesystem, should use doubles. Partly this is due to

non-determinism risk, partly due to speed. While I think this is a

useful guideline, I don't treat using doubles for external resources

as an absolute rule. If talking to the resource is stable and fast

enough for you then there's no reason not to do it in your unit

tests.

Speed

The common properties of unit tests — small scope, done by the

programmer herself, and fast — mean that they can be run very

frequently when programming. Indeed this is one of the key

characteristics of SelfTestingCode. In this situation

programmers run unit tests after any change to the code. I may run unit

tests several times a minute, any time I have code that's worth

compiling. I do this because should I accidentally break something,

I want to know right away. If I've introduced the defect with my

last change it's much easier for me to spot the bug because I don't

have far to look.

When you run unit tests so frequently, you may not run all

the unit tests. Usually you only need to run those tests that are

operating over the part of the code you're currently working on. As

usual, you trade off the depth of testing with how long it takes to

run the test suite. I'll call this suite the compile

suite, since it what I run it whenever I think of compiling -

even in an interpreted language like Ruby.

If you are using Continuous Integration you should run a test

suite as part of it. It's common for this suite, which I call the

commit suite, to include all the unit tests. It may

also include a few BroadStackTests. As a programmer you

should run this commit suite several times a day, certainly before

any shared commit to version control, but also at any other time you

have the opportunity - when you take a break, or have to go to a

meeting. The faster the commit suite is, the more often you can run

it. [2]

Different people have different standards for the speed of unit tests

and of their test suites. David

Heinemeier Hansson is happy with a compile suite that takes a few

seconds and a commit suite that takes a few minutes. Gary

Bernhardt finds that unbearably slow, insisting on a compile suite

of around 300ms and Dan Bodart doesn't want his commit suite to be

more than ten seconds

I don't think there's an absolute answer here. Personally I don't

notice a difference between a compile suite that's sub-second or a

few seconds. I like Kent Beck's rule of thumb that the commit suite

should run in no more than ten minutes. But the real point is that

your test suites should run fast enough that you're not discouraged

from running them frequently enough. And frequently enough is so

that when they detect a bug there's a sufficiently small amount of

work to look through that you can find it quickly.

Notes

1:

I say "these days" because this is certainly something

that has changed due to XP. In the turn-of-the-century debates,

XPers were strongly criticized for this as the common view was that

programmers should never test their own code. Some shops had

specialized unit testers whose entire job would be to write unit

tests for code written earlier by developers. The reasons for this

included: people having a conceptual blindness to testing their own

code, programmers not being good testers, and it was good to have a

adversarial relationship between developers and testers. The XPer

view was that programmers could learn to be effective testers, at

least at the unit level, and that if you involved a separate group

the feedback loop that tests gave you would be hopelessly slow.

Xunit played an essential role here, it was designed specifically to

minimize the friction for programmers writing tests.

2:

If you have tests that are useful, but take longer than you want

the commit suite to run, then you should build a DeploymentPipeline

and put the slower tests in a later stage of the pipeline.

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1104 followers