How I Learned to Love the Bard

by Kiersten Hallie Krum

William Shakespeare’s official birthday (though the actual date is not known for sure) was last week. He looks good for being 450 years old.

I came late to appreciating Shakespeare and spent my high-school years and some of college wondering what the hell the big deal was about such convoluted language and pretentious posturing on the stage. I saw it; I read it. I just didn’t “get it”.

Tho never shalt hear herald anymore

And then came Kenneth Brannagh’s Henry V during my sophomore year of undergrad and for the first time, Shakespeare became more than just something to be endured. Brannagh’s Henry took the material down from loftier “forsooth” and “verily” places of exact pronunciation and prestigious poses. Instead it was viscerally real, deeply emotional, included a few moments of romantic comedy— “Can any of your neighbors tell, Kate? I’ll ask them”—and resonated with great risk for questionable reward.

Much of my fondness for this play comes out of Brannagh’s and Emma Thompson’s performances, true, but therein lies the point: Shakespeare is meant to be experienced, to be performed, if it’s to really resonate. I don’t think I’ve ever laughed as hard at anything as I did the first time I saw Twelfth Night but reading it alone doesn’t illicit the same response. Even so, there wasn’t a switch that flipped when I first saw Henry V; it took several viewings for me to understand all that went on and once a line by line reading of the text while I watched the movie. I still struggled with the language and much of the convoluted plot points and why what was happening when. But in my gut, I finally Got It. And then came Brannagh’s Much Ado About Nothing and I Really Got It.

You have witchcraft in your lips.

I’ll never be a Shakespeare scholar—my one bout of serious study on the matter was while a student at Oxford and resulted in the lowest grade of my short tenure there—but I’ve come not only to love the language but to reveal in it. It is rich and meaty, a tangle of lexicon I delight in unraveling to limited comprehension, I’m sure. In learning to love Shakespeare, I learned to celebrate the richness of language and its many complexities and that has colored how I speak and write ever since.

I gravitate toward the comedies and the tragedies before the romances because Shakespeare’s idea of romance and women mostly reflects the time he lived in when marriage was a bargain between two houses and women second-class citizens at best. I find that his best representations of love aren’t found among the Romeos and Juliets, but rather in the B stories of other plays where he habitually depicts clever women of great strength.

Princess Katharine’s role may be small and short, but she’s key to the political proceedings and Henry is smart enough to recognize this. He makes her hand in marriage a nonnegotiable part of the peace. Katharine has no choice in these decisions that direct her life, she’ll go and marry where and to whom she’s told, but she still makes Henry work for her acquiescence. More, knowing her value, he pursues her for it.

Unhappy as I am, I cannot heave my heart into my mouth. I love your majesty according to my bond, no more no less.

—Cordelia, King Lear, Act 1, Scene 1

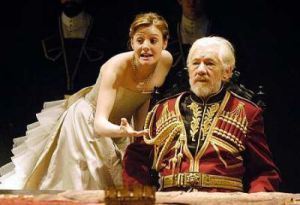

Though there are more ladies in King Lear than are in Henry V, Cordelia in has the least time on stage and on the page and yet she has enormous impact. She knows her father curies adoration he has not earned by holding his kingdom as ransom against his daughters’ protestations of love. She’s afraid; she can see what’s coming. She watches her sisters pontificate and lie and sees them gain for it and knows she cannot possibly do the same.

Why have my sisters husbands if they say they love you all? Haply when I shall wed that lord whose hand must take my plight shall carry half my love with him, half my care and duty. Sure, I shall never marry like my sisters, to love my father all.

It’s not a decision she makes lightly either. Cordelia knows the risks. She will almost certainly lose her father and her place at court and with that, she’ll most likely lose her royal fiancé, the King of France. She could lose any chance of having even a roof over her head much less a head still on her shoulders. A fickle king such as her father won’t hesitate to punish the insult to his pride and repent later. But Cordelia won’t play Lear’s game no matter the cost. When finally her father challenges her, she speaks the truth, literally risking it all rather than prop his ego up with more lies for profit.

Her fiancé could’ve turned against her as she’s disinherited. Instead, he takes her to safety, marries her, and later provides the army by which she eventually comes to her father’s (thwarted) rescue. Cordelia pays for her honest love with her life (naturally; it is Shakespeare after all) but not before she’s restored to her now-penniless father’s grace as, in his madness, Lear learns the truth of things (as so often happens) as elder daughters Regan and Goneril scheme and betray him.

But then there was a star danced, and under that was I born. —Beatrice, Much Ado About Nothing, Act 2 Scene 1

There are so many things to love about Beatrice and so much about Much Ado About Nothing that is pure gold. This line is one of my favorites. It comes after Beatrice has refused the duke’s sincerely offered hand in marriage. Her frankness and honesty are deeply valued by the disappointed duke as she playfully eases the sting of her rejection by saying that he is “too costly to wear every day.”

Your grace is too costly to wear every day.

After excusing that she was “born to speak all mirth and no matter,” Beatrice settles into silence. The duke chides her for her late-placed reticence in his presence, claiming that “to be merry best becomes you for out of question, you were born in a happy hour.” Beatrice counters that, in fact, her mother cried when she was born, “but then there was a star danced, and under that was I born.”

Beatrice’s fierce honesty is so much a part of her makeup. She does not suffer fools, not even when she’s in love with one. She is unquestionably secure in herself and needs not a man to make her whole. “Well niece, I hope to one day see you fitted with a husband,” her uncle lectures. Beatrice immediately replies:

Not till God make men of some other metal than earth.

Would it not grieve a woman to be overmastered with a piece of valiant dust? To make an account of her life to a clod of wayward marl? No, uncle, I’ll none. Adam’s sons are my brethren, and truly I hold it a sin to match in my kindred.

I would not deny you, but, by this good day, I yield upon great persuasion, and partly to save your life, for I was told you were in a consumption.

Indeed, Benedict is her equal, not her conqueror, and it is only after he recognizes and concedes that fact that they are able to reach their happy ending, and they reach it without Beatrice compromising herself or her nature to get there.

A few years ago, I discovered When Love Speaks, a CD of renowned British actors and musicians reading and sometimes singing Shakespeare sonnets and other snippets from the canon. While I’ve never seen or read The Tempest (yet), this bit from the demon Caliban, read by actor Joseph Fiennes, ends with this quote that speaks to every dreamer.

“And then in dreaming, the clouds methought would open and show riches ready to drop upon me that when I waked, I cried to dream again.”

Happy Birthday, Shakespeare. Thanks for teaching me to love the music of words.

Follow Lady Smut. We’ll teach you to love all kinds of things.