“Of Better Worlds and Worlds Gone Wrong” by Katherine Addison

I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark.

I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark. (Definition from TV Tropes here, for those who need it.) And I need to say, before I start, that I am a practitioner of grimdark; the Doctrine of Labyrinths quartet (Melusine (2005), The Virtu (2006), The Mirador (2007), Corambis (2009)) can be nothing but. So I’m not speaking as someone who abhors grimdark, but as someone who loves it.

One of the things behind grimdark, I think–and it’s not just grimdark, either, but most of Anglophone literature since somewhere around World War I–is a conviction that being pessimistic, tragic, depressing, dark means that a text is more “realistic,” more “serious,” and therefore inherently “better” than it would be if it allowed optimism and hope. I’ll get into the issue of “realism” later, but I want to point out here that tragedy is not inherently “better” as a literary form than comedy and writing a tragedy does not demonstrate greater skill/talent/genius than writing a comedy. (Kind of the reverse, in fact. Comedy is hard.)

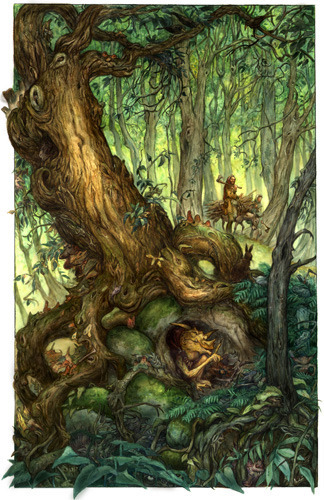

Art by David Wenzel

I’m not stumping for Pollyanna-ism. I don’t want to reverse the polarity and insist that sweetness and light is superior to gritty dystopianism. (I like grimdark, remember.) But dystopias that entirely deny the existence of virtues like compassion and altruism (1984, A Clockwork Orange, The Lord of the Flies) may be great literature, and great cautionary tales, but the more we accept and promote them as “more realistic” and “better,” the more we make it likely that they become more accurate mirrors of our species. If nobody models compassion, how is anyone supposed to learn to practice it?

I can feel the word escapism! loitering around the edges of this post and trying to shove its way in

I can feel the word escapism! loitering around the edges of this post and trying to shove its way in, because that is of course the way that followers of “serious,” “realistic” fiction denigrate any suggestion that not everything has to be one dreary disaster after another. Also, of course, escapism! is something that gets yelled at fantasy a lot (like albatross! in the Monty Python sketch) to beat it down and persuade us all that fantasy isn’t important and doesn’t matter, that it’s trivial and childish and unworthy of our attention.

J. R. R. Tolkien and Ursula K. Le Guin, two of the greatest fantasists of the twentieth century, had (have) strong opinions on the subject of escapism, which I’m just going to quote–Tolkien at great length, because he’s STILL NOT WRONG.

Tolkien, in “On Fairy-Stories”: “I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.”

Le Guin, riffing off Tolkien in “Escape Routes”: “If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The moneylenders, the knownothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.”

(Thank you to The Tolkienist for putting these two passages side-by-side.)

Art by Karl Kopinski

Tolkien and Le Guin are arguing that escape means hope, and hope is one of the great virtues of fantasy.

My point, aside from remarking that both Tolkien and Le Guin are arguing that escape means hope, and hope is one of the great virtues of fantasy, is what Tolkien says at the end of the passage: they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. Because I think that’s exactly it. The denigration of “escapism” comes from an implicit belief that it is brave and necessary and heroic to face “reality,” where “reality” is grim and dark and nihilistic (“solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” as that tremendous pessimist Thomas Hobbes puts it), and that if you turn away from that “reality,” you are a deserter and therefore a coward.

There are a number of fallacies here, as Tolkien notes. One is the claim to the exclusive right to define “reality.” Second, if this is an accurate definition of “reality,” it is a fallacy to believe that it is even possible to desert from the front lines by anything short of suicide. Even if your consumption of fiction takes you away from “reality” for an hour or two, you’re always going to have to come back. Clearly, if we accept this definition of “reality,” “escapism” can only be the most tremendous blessing fiction has to offer.

But going back to that first fallacy . . . “Reality” is not simple to define (as my persistent use of quotes is meant to indicate), and just because a literary movement or several have chosen to privilege and valorize darkness and gritty brutality doesn’t actually mean that that represents “reality” any more than My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic or The Care Bears (that plague of my own childhood) does. (It’s completely unfair to pick animated TV shows for children as examples, since they’re not even pretending to be real, but–I note for the record–they are trying to model virtues like sharing and loyalty and kindness to their small viewers.) Representing reality in fiction is an oxymoron anyway (even though it’s one that I, like many other writers, strive to resolve as best I can in my work); there’s no need to compound the problem by artificially limiting what counts as “reality” and what doesn’t.

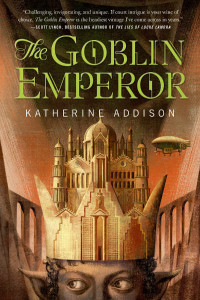

Buy The Goblin Emperor by Katharine Addison: Book/eBook

Cynicism is fashionable in the current grimdark era, the attitude that we are too smart to be taken in by idealism. And god knows it’s true that human beings are capable of evil–not only of committing atrocities, but of reifying atrocity into a cultural ethos. (I read a lot about Nazi Germany. Believe me, I have no illusions about human nature.) But human beings are also capable of breathtaking self-sacrifice and compassion and grace, and denying that gives as false a view of human nature as denying our capacity for evil.

And that, I think, is where hope comes in. If we understand “escapism” as the Escape of the Prisoner rather than the Flight of the Deserter, then surely what motivates it, more than anything else, is hope. The hope that the prison is not eternal. The hope of communicating with other prisoners. The hope that if you keep chipping away at the bars long enough, one of them will fall out. And I refuse utterly to classify that hope as weak or foolish.

“No live organism,” Shirley Jackson wrote at the start of The Haunting of Hill House, “can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute realism; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream.” Fantasy allows us to dream–both of better worlds and of worlds gone wrong. And we need them both.

The post “Of Better Worlds and Worlds Gone Wrong” by Katherine Addison appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.