National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Michael J. Rosen: A Journey with Haibun

While I’ve been writing haiku (or what works for me as haiku) for 13 years, I’ve only recently worked in the form of haibun (or what works for me as haibun). It’s another traditional Japanese poetic form whose particular stylistic and formal constraints—structure, subject matter, length, point of view, etc.—“translate” from the Japanese language into the English language about as improbably as something from the 17th century does into the 21st.

Portrait of Matsuo Bashō by Takebe Socho.

The haibun, attributed to the poet Matsuo Bashō, is a passage of concise, imagistic prose, followed by one or more haiku. Conventionally, it’s an imagistic depiction that is part of a journal or journey.

I can’t read Japanese, but I’ve read countless poems in translation, as well as historical overviews of Japanese forms, and individual writer’s arguments for what, in a given form, is required, isn’t acceptable, and so forth. So even as I value the intricacies and linguistic challenges in haiku and haibun, I feel comfortable participating in the evolution of these forms—this is why I added the phrase “what works for me” above. I approach each form as a structure. As rules for a game. As a set of challenges that restricts and, more crucially, reveals content. I choose form as an inspiration rather than an institution.

Regarding the haibun, I adhere to these underlying principals:

• Neither is the prose merely a set-up for the haiku, nor is the haiku a conclusion or culmination of the prose. Yet the prose and poem should link. A connection that leaps forward or sideways. Perhaps an avatar or shape-change. Perhaps a shift in time or place or logic.

• Consider the haibun more of a regular practice than a perfect execution. Think of it like practicing yoga: It’s about spending focused, challenging time in a very mindful present. Neither is success the execution of one particular poem/yoga posture, nor is failure about writing something faulty/falling out of a posture. Take the work as close to what’s possible in a short period of time.

• Think of haibun as a watercolor in a sketchbook: Find the idea for a composition. Render it quickly. Apply color without fussing. Leave unfinished areas, white space, drips, bleeds, traces of the sketch. Stop before it’s finished. Start another “painting” that might “solve” or continue what this first work has just suggested.

• Have no thoughts about whether one particular work is worthy. It’s the ongoing work—the ever evolving work—that is.

Here are a few examples. They’re excerpts, really, meant to suggest the larger enterprise.

Cardinals

Any night I can, I sleep with the sliding-glass doors in the bedroom open. I drift off to the grumbling of the koi pond’s fountain. I wake to the chortling of the Northern Cardinals: What cheer, cheer, cheer….

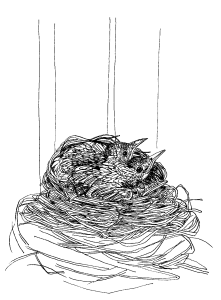

Robin nest, illustration by MJR from his forthcoming book, GEORGICS.

I wish I could recognize each pair that joins the morning rush hour at the feeder. I know they’re residents of this place, just as I am. The male and female both sing throughout the day; paired for life, they usually return to the same nesting area each year. The males will keep up the singing all day, declaring their territory as if each note of their song were twisting into a barbed wire staff to fence out other cardinals.

When the sun sets, the cardinals are the last at the feeder. All that “cheer” must take a lot of energy; it’s only darkness that gives them a chance to be quiet—gives the night birds—chimney swifts, mockingbirds, owls—a chance to be heard.

And every night, as in a creation story, their artful “wire” unravels, so the work of singing must resume the next day, with equal, unabashed ardor.

morning cardinals

calling—does it wake me or

do I wake to it?

All Gray Day

Stunned at the gray’s relentlessness. All of yesterday. Entirely unpredicted. Not a drizzle or drop of rain. But a solid, cloudless gray fixed itself in the sky as if the Earth had stopped moving for a day or the atmosphere had backed up in some meteorological traffic jam, each cloud rubbernecking to see some accident that had long cleared up.

hey! all-day-gray sky

can’t you crack even one smile

of sunshine, just one?

Hummingbird Leaves

The hummers have returned: the same ones who will summer here the rest of their short lives. Over the winter, their favorite ornamental dogwood next to the deck died. No reason I can tell. I appreciate that trees grow old as well as bigger and taller.

Now the birds perch at the tips of bare branches, buzz over to the feeders for a few sips, fly a lap around the lawn or zigzag over to another tree…and then buzz back for another perch. Repeat. Repeat. In the skeletal tree, they’re the only green. Mockingly, they appear to be a few shiny spring leaves.

Yes, I need to take the chainsaw to the dogwood. I need to plant something new, which will take more years than are left to me in order to reach the second-floor deck where the hummingbird feeders ring in summer. (I should investigate the fastest-growing trees.) Even these hummers will have to pass along this destination to their next generation. On average, they only live three or four years. The smaller the creature, the faster it burns through life.

But even we big creatures wish each summer would come at us more slowly.

green leaves on the dead

dogwood: hummingbirds…tinged red—

no, too soon for fall!

Trails

Windstorm. Clearing trails of snapped branches, climbing over or around the downed trees I’ll return to saw later, I unceremoniously inventory the other limbs and trees that fell—but not on the path I’ve made. They will remain where they are: suspended in another tree’s canopy; pining nearby saplings to the ground; collapsed on another rotting tree; shattered at the border of a neighbor’s meadow. It’s only where I want to go…that’s of concern. If there weren’t a path, I’d have nothing to clear. Again. And again.

single-file deer path

now…our steps retrace theirs…now

their steps retrace ours

Living Lawn Art

There was a peacock in the front meadow. It strolled in a straight line as if crossing the street where a patrol was halting traffic. Sure, my brain was about to perceive “wild turkey” (a most familiar, somewhat similarly shaped visitor) when the reality of “peacock” lit up my brain as if the word itself were fanning open like the bird’s feathered train.

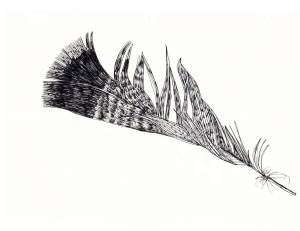

Wild turkey feather illustration by MJR from his forthcoming book, GEORGICS.

Do we have wild peacocks out here…? Hardly: They’re native to India. Did someone have one as…part of a natural alarm system? True: While this particular bird didn’t utter a peep, I’ve heard these peafowls’ amazing shrieks. Some sound like a kitten’s voice ramped up and amplified for a soundtrack in a horror flick. Some sound like an elephant’s trunk blasting one of those feathered, uncurling party whistles. Still others sound like a bullwhip took a long inhale from an empty whipping cream dispenser before some cowboy cracked it on the pavement.

If only this visitor sticks around long enough for me to hear all those vocalizations.

So I checked online to read if there’s any chatting about these birds in my area, rural Central Ohio. On one blog I read: “Only purpose for having peacocks is their beauty. I don’t know of anyone who eats them. They are living lawn art, but other than that, they are very loud and useless birds.”

As soon as beauty becomes “useless,” I will be out of business, and the world won’t be worth the trouble that keeps it spinning.

its tail fanning out

a thousand eyes stare, surprised

at your own surprise

Michael J. Rosen.

Michael J. Rosen is the creator of a wide variety of more than 100 books for both adults and children. A poet, fiction- and non-fiction writer, humorist, illustrator, editor, and, as of 2013 and the premier of “Elijah’s Angel: A Play for Chanukah and Christmas,” a playwright.

Rosen’s many children’s books, such as CHANUKAH LIGHTS, a poetic collaboration with pop-up master Robert Sabuda (Candlewick); BONESY AND ISABEL (Harcourt); and ELIJAH’S ANGEL (Harcourt), have received many distinguished citations, among them, the Sydney Taylor Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries, the National Jewish Book Award, the inaugural Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance Once Upon a World Book Award for the best children’s book that promotes diversity and tolerance, and the Ohioana Library Career Citation in children’s literature. Fifteen of his books such as DOG PEOPLE and HORSE PEOPLE (Artisan), HOME (HarperCollins) and THE GREATEST TABLE (Harcourt), were created with the generosity of hundreds of the country’s best-known illustrators, photographers, authors, and cartoonists as creative philanthropy. Their profits benefitted the Share Our Strength’s work to end childhood hunger and a granting program he created, The Company of Animals Fund, that awarded over $375,000 to 100 animal welfare organizations.

For over 40 years, ever since working as a counselor, youth-services director, day-camp director, and teacher at local community centers, Michael has been engaged with young children, their parents, and teachers. He has taught poetry and other forms of creative expression to adults and youth at literature conferences, colleges, libraries, and many nontraditional learning environments. As a visiting author, in-service speaker, and professional workshop leader, he has traveled to well over 700 schools and conferences around the nation.

Recent books include: a six-book series of nonfiction humor for third/fourth grades entitled NO WAY! that features a volume on world’s most eccentric sports, jobs, foods, buildings, medical practices, and forms of transportation (Millbrook/Lerner Books); a novel in poetry and two voices, RUNNING WITH TRAINS (Wordsong) set in 1969 that interweaves the lives of a divorced boy commuting between cities on the B&O Railroad and a younger farm boy whose land the railroad crosses; and SAILING THE UNKNOWN: Around the World with Captain Cook, a free-verse diary of a stowaway aboard the ship Endeavor (Creative Editions).

Among his forthcoming books are THE HIMALAYAN’S HAIKU AND OTHER POEMS FOR CAT LOVERS (Candlewick); GIRLS VS. GUYS: The Surprising Differences between the Sexes (Twenty-first Century Books); and a picture book, THE FOREVER FLOWERS (Creative Editions).

His poetry for adults has been collected in three volumes: A DRINK AT THE MIRAGE (Princeton University Press), TRAVELING IN NOTIONS: The Stories of Gordon Penn (University of S. Carolina Press), and TELLING THINGS (Harcourt Brace). A fourth collection, GEORGICS, is in production at Cat Steppe Press.

He lives on a 50-acres in the foothills of Appalachia, east of Columbus where he served for nearly 20 years as literary director of The Thurber House, a cultural center in James’s restored boyhood home. During his tenure, Rosen edited four volumes of James Thurber’s work, and began the first of three humor biennials, Mirth of a Nation.

Michael’s Website is www.fidosopher.com.