An education framework based on knowledge modelling

By Gordon Rugg

Education is about getting new content into student’s heads, via some combination of teaching and learning.

In order to do this in an evidence-based way, one key element is a solid categorisation framework for each of the variables involved. Three key variables are:

Types of content

Types of delivery

Types of learning

There are other important variables, such as physiological constraints, but we’ll focus for the moment on the three listed above.

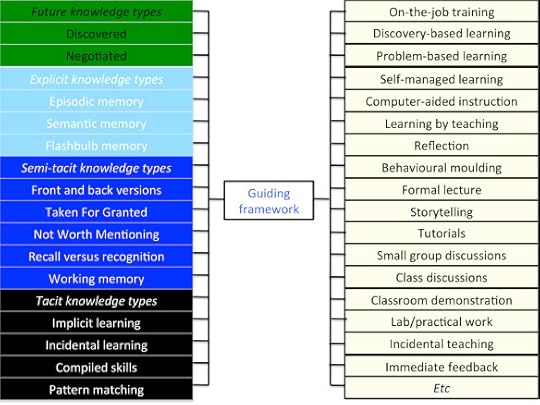

Existing educational categorisations, such as the Visual/Auditory/Kinaesthetic model, tend to be unsystematic and/or very coarse-grained. In order to handle this area properly, a category system should as a minimum be able to handle systematically the types of content and of delivery and learning shown in the diagram below, and preferably be able to handle more.

This article is a brief overview of how we have been tackling this issue. We will go into more detail in later articles.

In the diagram above, the categorisation of content is the same one that Neil Maiden and I used in our work on requirements acquisition, in our ACRE framework.

That framework contains four main types of content (which we called “knowledge” as a shorthand term for various forms of content, communication and skill) and a way of mapping each of these onto appropriate methods for eliciting that type of knowledge from a respondent.

The first of these types, future systems knowledge, is a significant issue for product development, where the client often cannot know what their detailed requirements will be, since they are dealing with a novel product that does not currently exist.

In education, this issue is highly salient for students choosing academic options and career paths, where by definition the students will not initially have enough information to make an informed choice, and where there has to be an iterative process of information-gathering, partial choice, and further information-gathering.

Explicit knowledge in this framework is knowledge to which the individual has reasonably accurate access via introspection. For example, when the student remembers the date of a particular event, they are drawing on explicit knowledge.

Explicit knowledge is liable to various well-established biases and distortions. Human memory is fragile and liable to distortion both when storage occurs and when memories are retrieved, as shown by a substantial body of work by researchers such as Elizabeth Loftus and Alan Baddeley. For instance, simply altering the wording of a question can significantly change a respondent’s memories for what they saw.

A lot of the content in education is explicit, but even more content is not explicit. Simply lumping this other content into a single dustbin category of “tacit” or “subconscious” is not very helpful. The next two parts of the ACRE framework identify two main categories and various sub-categories that involve content which is not explicit.

Semi-tacit knowledge is accessible via some routes, but not via all routes, unlike explicit knowledge.

A classic example is recognition (passive memory) versus recall (active memory). If you ask a student to list all the countries of Europe, they will usually produce a partial list. If you then show them a mixture of real countries that they haven’t named and of imaginary or non-European countries, the student will usually be able to identify accurately a number of other European countries that they had not been able to recall initially. It’s clear from the fact of recognition that the knowledge was in the student’s brain, but despite this, the student was not able to access it consciously. This isn’t an issue of motivation – quiz shows are an everyday example of people being unable to recall information that they know, even though there are large incentives to recall it. Instead, it’s an issue of how human memory works.

There are various types of semi-tacit memory; for brevity, I won’t go into them here, but we’ll blog about them in later articles. If you want to do some background reading, the types listed in the diagram are all based on well-established concepts from the literature, that can be easily found online.

Tacit knowledge in this framework is knowledge to which the individual has no valid introspective access – in other words, the person can use the knowledge (or skill, or whatever) but does not actually know just how they are using it, or what it is. A classic example is an experienced driver changing gear without knowing exactly which actions they perform in which sequence.

This definition of tacit knowledge is stricter than the one often used in the business literature, where “tacit” covers both the strictly tacit knowledge described above and also the semi-tacit types described above.

Tacit knowledge often involves muscle memory and/or very large amounts of practice and rehearsal, with significant implications for learning and delivery.

Learning and delivery types

An education theory should not only have an adequate categorisation system; it should also have an empirically grounded framework that guides the matching of particular types of content with appropriate types of delivery and learning.

In the ACRE framework, Neil Maiden and I mapped the various types of knowledge onto appropriate techniques for eliciting each type of knowledge.

In more recent work, Sue Gerrard and I have started to examine ways of mapping various knowledge types onto appropriate techniques for learning and teaching each of the knowledge types.

We have also drawn on the Verifier framework of human error, described in my book Blind Spot, to identify ways of making key content more memorable by using biases in human memory as an asset.

This article is a preliminary overview of our approach.

We’ll be exploring some of these issues in detail in future articles.

Notes

The image above is copyleft Hyde & Rugg. You’re welcome to use our copyleft images for any non-commercial purpose, including lectures, provided that you state that they’re copyleft Hyde & Rugg.

There’s more about the theory behind this article in my latest book:

Blind Spot, by Gordon Rugg with Joseph D’Agnese

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Blind-Spot-Gordon-Rugg/dp/0062097903

Related articles:

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2014/03/23/false-dichotomies-in-education-theory/

http://hydeandrugg.wordpress.com/2013/05/27/the-verifier-approach-part1/

Rugg, G. & Gerrard, S. (2009). Choosing appropriate teaching and training techniques. International Journal of Information and Operations Management Education 3(1) pp. 1-11.

Rugg, G., D’Cruz, B., Foreman-Peck, L., Grimshaw, E., Guilford, S., Roberts, S. & Tonglet, M. (2008). Selection and use of elicitation techniques for education research. International Journal of Information and Operations Management Education 2(3) pp. 235-254.

Maiden, N.A.M. & Rugg, G. (1996). ACRE: a framework for acquisition of requirements. Software Engineering Journal, 11(3) pp. 183-192.

Gordon Rugg's Blog

- Gordon Rugg's profile

- 12 followers