National Poetry Month: Guest Post from Emily Jiang: Summoning Li Bai

Poetry is one of my greatest passions, and I memorized poems before I learned how to read and write. The first poem I learned by heart from my parents was a poem written over one thousand years ago in China by a one of the country’s most famous poets, Li Bai (701-762).

Here is the poem in Chinese:

夜思

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故鄉

Li Bai In Stroll, by Liang K’ai (1140–1210).

Here’s my translation (co-translated with C.L. Jiang) of the poem into English:

“Night Thoughts” by Li Bai

Before my bed I see moonlight so white

I think it is frost on the ground.

I raise my head to look at the moon so bright

I bow my head, yearning for my hometown.

If you look closely at the original Chinese poem, the phrase “bright moon” (明月) appears twice, first time in the first line and second time in the third line. After much discussion with my co-translator, I made a conscious decision not to repeat “bright moon” but to change my translation fit the context for a Western reader. I substituted “white” for “bright” because I thought “white” would make more visual sense for “frost on the ground.”

The original Chinese poem of has a very strict structure of five syllables per line with end rhymes. When translating this poem, I chose be looser about the amount of syllables per line, but I also decided to make it rhyme, just like the original poem. However, I changed the rhyme scheme. The original poem in Chinese has a rhyme scheme of A A B B, where the endings of the first two lines share the same rhyme while the endings of the second two lines have a different rhyme. I mixed up the rhyme to be A B A B. True, “ground” and “hometown” is not a precise rhyme, but the vowels and end consonants are similar enough. Contextually, I also liked ending those lines with a concrete sense of place, contrasting with the heavy moon focus of the first and third lines, and reinforcing poem’s theme of homesickness and displacement. In short, the rhymes make the poem more poignant.

Shen’s Books, March 2014.

As I grew older, the poems of William Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, Louise Gluck, Sylvia Plath, and many, many more joined the few ancient Chinese poems I learned as a young child. Although I hold a BA in English and an MFA in Creative Writing (in English), I do think my childhood exposure to Chinese poetry has influenced how I write poetry in English, and my style tends to be more sparse, less florid.

One of the biggest questions-turned-compliments I’ve received from a reader of my new picture book SUMMONING THE PHOENIX was “Who wrote the original Chinese poem?” The poem referenced was “Painting with Sound,” my own original poem. Here it is:

“Painting with Sound”

Picking at my guzheng,

I can feel

the crisp, clean

mountain air

breezing over

my unbound hair.

Strumming my guzheng

I can feel

the cold rush

of waterfall

filling my ears

with thunderous call.

In this poem I wanted to incorporate different senses, as evoked by the title, which mixes the visual (painting) with the auditory (sound). So in the body of the poem, I evoke nature as perceived not through the eyes but through the sense of touch (breezing over / my unbound hair) and through hearing (filling my ears / with thunderous call).

Apparently, I had captured enough of a flavor of Chinese poetry to convince the reader that it was an English translation of a Chinese poem. I was so flattered! Yes, ancient Chinese poets often wrote about music, though the subject matter was more heavily favored to the pipa (aka the Chinese lute) vs. the guzheng. But perhaps the reader was more influenced by the dramatic and gorgeous artwork that is the backdrop of “Painting with Sound.”

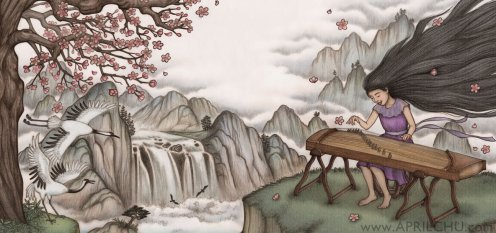

With illustrator April Chu’s permission, here’s her stunning artwork that accompanies my poem “Painting with Sound”

Illustration by April Chu.

I absolutely love how her artwork fills in the visual details of the mountain and waterfall that I deliberately left out of the poem. April brilliantly added wonderful details that are not in the poem: the cranes and the cherry tree, with its blossoms floating across the vast expanse to land in the girl’s hair and in front of her bare feet! Also, instead of a traditional Chinese outfit, the girl is wearing contemporary American clothes because she is a contemporary American, with some Chinese influences, just like the me.

Writing the poems for SUMMONING THE PHOENIX was such a wonderful experience, and I hope my readers enjoy my book. If playing music is painting with sound, then writing poetry is painting with words!

Emily Jiang.

Emily Jiang is the author of SUMMONING THE PHOENIX: Poems & Prose about Chinese Musical Instruments, illustrated by April Chu and published by Shen’s Books, an imprint of Lee & Low Books. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Saint Mary’s College of California, where she studied Craft of Poetry with Brenda Hillman and Graham Foust, and a BA in English from Rice University, where she studied poetry with Susan Wood. Her co-translations of ancient Tang Dynasty poetry can be read in Interfictions and Stone Telling. Her original poems have been published in several magazines and anthologies, including Stone Telling, Strange Horizons, Goblin Fruit, and THE MOMENT OF CHANGE anthology of speculative feminist poetry. She blogs at www.emilyjiang.com.