Laurie Colwin — my mentor in the kitchen & on the page

I once bought a black speckled canning pot, two boxes of Ball jars, and twelve pounds of dusky Italian plums in memory of an author I loved.

I once bought a black speckled canning pot, two boxes of Ball jars, and twelve pounds of dusky Italian plums in memory of an author I loved.

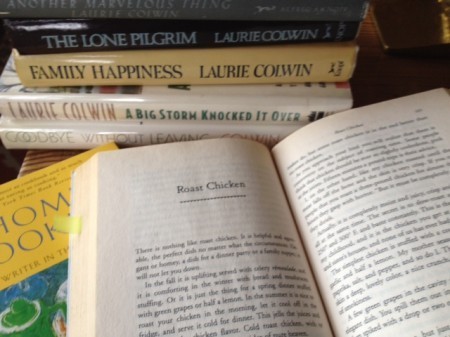

For years, I’ve suspected I was one of a few remaining Laurie Colwin aficionados, a smallish but loyal band of readers of a certain age and sensibility who still hold her close in our hearts, afford her books prime space on our shelves, and continue to make her signature dishes in our kitchens.

So it was rather wonderful, though a bit startling, to discover in the pages of the New York Times this week that I’m not alone after all. That in fact, in the more than twenty years since her death, Laurie’s following has only grown, attracting “a new, cultishly devoted generation of readers,” many of whom are in their thirties or even younger.

Turns out, Laurie Colwin is bigger than ever. Her books, never out of print, are selling briskly. Some of her most zealous disciples today were toddlers when she died in 1992. Somehow, knowing about her expanding fan base gives me hope — not only for this new generation of readers, secret romantics, and home cooks, but also for the survival of such humble institutions as tea parties, afternoon picnics, and family dinners.

I knew Laurie only slightly. Back in the mid-eighties, she agreed to read in a short story series a friend and I were producing, pairing well-known writers with our latest literary discoveries. We’d barely been introduced backstage when Laurie asked if I would retie her scarf, a slippery, oversized square of silk that proved impossible for either of us to get just right.

I knew Laurie only slightly. Back in the mid-eighties, she agreed to read in a short story series a friend and I were producing, pairing well-known writers with our latest literary discoveries. We’d barely been introduced backstage when Laurie asked if I would retie her scarf, a slippery, oversized square of silk that proved impossible for either of us to get just right.

I was twenty-five, longing for passionate love and domestic bliss, and she was, hands-down, my favorite living writer. I often felt in those days as if I were meeting alternate versions of myself in Laurie Colwin’s stories, which I read and re-read as if they were medicinal. In a way, perhaps, they were.

Newly separated from a miserable but well-intentioned first marriage, I was ashamed of the embarrassing mess I’d already made of my life. Laurie’s characters — good, honorable souls all — often found themselves haplessly entangled as well. I found solace in their romantic missteps and hope in their ability to survive life’s ambiguities. “Falling in love is not a mistake,” insists a character in The Lone Pilgrim – curative words for my own bruised heart.

Backstage that night, my hands shook a bit as I fussed with the ends at her neck, trying to make them lie flat. I remember exactly what I was thinking: “Life is full of astonishment. I am standing in the wings of a New York theatre, tying Laurie Colwin’s scarf!”

After that, a mutual publishing friend began inviting both of us to his dinner parties. For a time, our paths crossed. I was always a bit in awe of her wit and charm, and I think she, fourteen years older and almost preternaturally maternal, liked the idea of keeping a watchful eye on me.

Once, after I’d fallen in love with my future husband and left New York to marry him, Laurie and I met for lunch when I was back in the city. She loved a romantic story with a happy ending and I was flattered that she wanted to hear every last detail of mine.

We sat outside at a deli around the corner from her Chelsea apartment. I know we shared an enormous corned beef sandwich at her suggestion, because later I wrote it down. She asked me about children and I told her, yes, I was trying — without success.

Laurie leaned across the table, suddenly intent, her face framed by a huge halo of untameable dark hair. What had I tried? What drugs had I taken? What was I doing and how often was I doing it? She was certain I needed to work less and eat more. Surely I needed more sleep, too. And I needed to see her doctor right away; she would make sure I got in. I was pushing thirty, she pointed out, and there was no time to waste.

It’s funny, the details the mind files away. And for me this one remains indelible: an impassioned Laurie Colwin insisting I had no time to waste. She wrote her gynecologist’s name on a white deli napkin and handed it to me. “Call him,” she said. “The man can get a stone pregnant.”

After lunch, we walked a few blocks to pick her daughter Rosa up at school and then back to their cozy, cluttered apartment. It seemed perfectly familiar, almost as if I’d been there before, though of course I hadn’t; I’d just read enough of Laurie’s descriptions of home to recognize hers: “small but crammed with artifacts: watercolors, family photographs, teapots, pitchers, and beautiful plates.”

We had tea in the kitchen as the late afternoon light streamed in. Less than six months later, I was pregnant. I never saw her again.

The news that Laurie had died, suddenly and in her sleep of heart failure, on October 23, 1992, stunned everyone. Her death seemed unfathomable – she was only 48; she had a young child, a husband; she was fully engaged in living and writing and volunteering at the soup kitchen near her home where she was on a first-name basis with all the regulars. And then, overnight, she was gone.

I was eight months pregnant with my second son, standing in the sunshine on our back porch in the suburbs when the call came from a friend. Although Laurie and I weren’t often in touch, I’d happened to talk with her just a few weeks earlier about being the guest editor the following year for The Best American Short Stories. I promised her we’d have fun. She hadn’t hesitated before saying yes. It took a few minutes before my tears began to fall, as if my heart simply refused to admit the news.

And yet, despite these brief but precious memories, my real relationship with Laurie Colwin has always been that between a writer and a reader. As a miserable twenty-three-year-old married too soon and to the wrong man, I wept and took heart reading Laurie’s short stories, encouraged by her conviction that there is a fine, flawed person at large in the world destined eventually to find his or her way to each one of us. Love, she believed, was unpredictable, often painful, sometimes blind, always worth waiting for. And, as her characters inevitably realize: even happiness takes work.

When I was home sick with a cold, or exhausted, or feeling sorry for myself, I’d take to my bed with a box of tissues and my favorite novel, Happy All the Time. Inevitably I’d come across a description of a restorative cup of tea, or a perfect cheese omelet, or a full-bodied glass of wine – descriptions so seductive that I’d always be roused to get up and wander into the kitchen to fetch a little something for myself. It was simple: when I was miserable in my twenties – whether due to matters of the heart, the spirit, or the body – reading Laurie Colwin made me feel better.

Later, married to the right man and raising our two children, I began to read Laurie’s essays about food with the same kind of deep, personal affinity I’d always felt for her fiction. She wrote about eating a tomato from the garden with as much rapture as another writer might bring to a climactic love scene. She could make eggs sexy, cold coffee appealing, lentil soup sound festive, old Bristish cookbooks compelling. She inspired me to throw more dinner parties, to “build” better sandwiches, to go in search of my first organic egg and to exhaust my arm stirring my first pot of polenta.

And she was surely the only writer on earth who could tempt me to cook a lima bean casserole, simply by recounting the contentment this unlikely party fare brought to the group of friends upon whom she bestowed it one wintery night.

For Laurie, it was all one in the same, romantic love blending seamlessly into culinary exuberance and from there into a generous, high-spirited passion for life itself. She was, like her heroine Polly in The Lone Pilgrim, a domestic sensualist, reveling in the enchantments of everyday existence. And although the essays that became Home Cooking and More Home Cooking were ostensibly about cooking and eating and feeding people, these two casually intimate volumes are in fact sublime celebrations of love and friendship and family – each one as much memoir as cookbook, the wealth of enticing recipes not withstanding. To step into these pages was to find a friend not only to stand at my side in the kitchen but to accompany me through the vagaries of my own newly domestic life as well.

Laurie’s essays – in which she somehow manages to be anecdotal, funny, affectionate, and informative all at once – shone a light on the path as I became a wife and a mother myself. Drawn into her confidence on the page, I felt as if I’d come to know at last this generous, quirky, brilliant woman who got dressed up every year for Halloween, ate stewed eggplant right out of the saucepan, and baked gingerbread on a weekly basis for her little girl.

You do not have to be a housebound mother to make gingerbread. All you need is to put aside an hour or so to mix up the batter and bake it, and then, provided you do not have a huge mob waiting to devour the gingerbread immediately, it will pay you back for a few days because it gets better as it ages.

Cooking, Laurie continually reminds us, needn’t be drudgery but rather an ongoing expression of affection and creativity. And the dinner table isn’t just a place to serve food, but also the ideal setting to create and sustain traditions, to nurture oneself and others, to weave the invisible mantle of memory and intimacy and security that holds us gently in place in a fast-moving world.

It took me a long time to get over my fear of making jam. The whole enterprise seemed terrifying. After all, entire factories were devoted to its manufacture, so how was I, one small person in an inadequate kitchen, supposed to compete?

Reading about Laurie’s “jam anxiety” I was surprised to discover she’d been as leery of sterilizing jars as I was. She was gone by the time I finally got around to trying jam myself, but I liked to imagine that somehow, somewhere, she was watching out for me still.

I bought the canner and my first load of ripe plums because she convinced me I was up to the job – which, of course, I was. For many years, making Laurie Colwin’s plum jam each October felt like a way of sustaining the ineffable, eternal thread that bound us, a writer who left the world too soon and her grateful reader, still here in it.

Perhaps we all look for guides and mentors along the way, people who suggest by example a way of being in their own skin that prompts us to take notice because it feels right to us, too — and even worth emulating. Laurie Colwin was that kind of guide for me, simply by living her life so fully and writing about it so generously. I would seek her advice on roasting a chicken and what I received along with it, always, was a reminder to savor my hour in the kitchen and the precious people gathered at my table for the meal.

Perhaps we all look for guides and mentors along the way, people who suggest by example a way of being in their own skin that prompts us to take notice because it feels right to us, too — and even worth emulating. Laurie Colwin was that kind of guide for me, simply by living her life so fully and writing about it so generously. I would seek her advice on roasting a chicken and what I received along with it, always, was a reminder to savor my hour in the kitchen and the precious people gathered at my table for the meal.

Throughout my years of editing and writing books and raising children to adulthood — as I brewed my morning cup of coffee, peeled carrots, baked bread with my little boys, put dinner after dinner after dinner on the table, listened to the rise and fall of deepening male voices and the clatter of silverware – I’ve thought of Laurie many times. The lessons she taught, both in her writing and by dying right in the middle of her living, have shaped me both as a person and as a writer. And certainly this is one: to fully embrace the delicious, irretrievable, ordinary moment that is now.

Throughout my years of editing and writing books and raising children to adulthood — as I brewed my morning cup of coffee, peeled carrots, baked bread with my little boys, put dinner after dinner after dinner on the table, listened to the rise and fall of deepening male voices and the clatter of silverware – I’ve thought of Laurie many times. The lessons she taught, both in her writing and by dying right in the middle of her living, have shaped me both as a person and as a writer. And certainly this is one: to fully embrace the delicious, irretrievable, ordinary moment that is now.

In the fall of 1992, in a burst of enthusiasm – or prescience? –Laurie composed a whole year’s worth of columns for Gourmet and sent them off to her editor. The magazine ran those pieces posthumously, and so it was that each month over the next year, as I negotiated the demands of an infant and a toddler, Laurie arrived in my house in the glossy pages of a magazine, sharing her recipes, her humor, her heart.

Her Thanksgiving column appeared in Gourmet the month after she died. A reflection on the evolution of her own Thanksgiving dinner, it included her recipes for cider jelly and rosemary nuts (a treat I continue to make and give away to this day). She concluded:

This menu is now my tradition, but I know that in not too long a time my daughter will grow up and decide that it is her turn, and we will travel to her household for Thanksgiving. And there I will find the traditional meal, totally renovated and redesigned: the beginning – for that is the way these things go – of a new tradition.

Last year, for the first time, my mother passed the Thanksgiving baton to me. I labored over the stove for two days, prepared her traditional meal for our family, and sighed with relief when she nodded her approval, aware that the end of one chapter had given rise now to the beginning of a new one. This, as Laurie observed, is “the way these things go.” Nothing lasts forever.

And yet, we show up for as long as we are able and we carry on anyway, passing the old recipes along, bringing out the good dishes, and reminiscing about years gone by – in the hope that we’ll have a chance to do it all over again next year.

For what do any of us wish for, really, other than to be granted another day just like this one? Another trip to the farmer’s market, a hummingbird in the garden, a sun-kissed tomato straight from the vine, a pot of soup to share with family and friends, a pan of dense, spicy gingerbread eaten warm—the immeasurable, ephemeral joy of life itself.

The post Laurie Colwin — my mentor in the kitchen & on the page appeared first on Katrina Kenison.

newest »

newest »

She was my favorite author, too.

She was my favorite author, too.