April Poetry: Take the Challenge and Get Your Poem Published

SLEEPING WITH FOXES

by Darcy Pattison c. 2003 All Rights Reserved

My favorite source of idle talk is from the soccer moms,

weekends, every Saturday.

This is how I go about gathering tidbits:

I set up my collapsible chair near the sideline and sit.

Then, I look through my collection of ears,

choose a robust pair, put them on and lean in close,

as if every word is pure gold and my existence consisted of only

rumor, innuendo, weird stories.

Then I take out my tongue and hold it in my lap.

I do this so that what I hear will be pure,

completely chaste,

uncontaminated by the chatterings of my voice.

One mother tells about her miniature Doberman,

how he jumped onto her bed

in a frenzy, like a mad yellow-jacket.

He didn’t stop until she got up.

She followed him to the living room,

unaware that bizarre things were taking place.

She flipped on the light and looked around

at the fireplace, the couch, the rug.

She had to rub her eyes: the neighbor’s cat

had come through the doggie door and sat on her favorite chair.

In between the cheers for the forward’s great header

and the keeper’s save, another soccer mom says,

That’s nothing, listen to this.

My ears glow red with joy.

I should mention, she says, that I like to watch

TV’s Strangest Home Videos.

I find it hard to ignore the temptation,

the true America.

The program shows extraordinary stories,

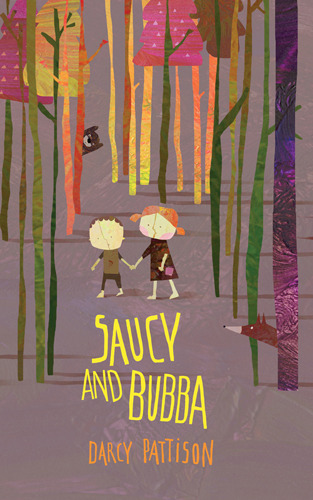

like the one about a boy who tells his parents

he sleeps with foxes. They don’t believe it.

The boy is sincerity itself: He insists that he sleeps

with a red fox every night.

After a spell, the parents decide to set up video cameras.

Then, they watch the boring tape until,

just at midnight, at the stroke of midnight,

they see a sly red fox come in the doggie door,

eat the dog food, trot down the hallway,

and jump onto the boy’s bed.

It curls itself around the boy’s head.

The horror-struck parents watch the pair sleep.

When the boy stirs lightly a few hours later, the fox leaves

the way it had come.

Afterward, when the keeper has saved his last goal,

the teams line up to slap hands.

I replace my tongue.

I take off my sullied ears and stow my collection

with my collapsible chair. Then I gather up

my soccer son, his soccer ball, his soccer gear,

and speed through the city,

barely making it through every yellow light.

My radio blares––

country or jazz or rock-and-roll, I don’t know––

And I listen to none of it because

all I hear is my voice rehearsing

the tale of a boy who sleeps with a sly red fox.