Leverage Sunday: The Bottle Job: External/Internal Character Arc

“The Bottle Job” is one of the last episodes in Season Two, the season of Nate Ford’s descent into darkness, and it’s the clearest indication that Nate is close to hitting bottom because it’s the clearest illustration that Nate’s internal conflict is hurting the way he directs the team’s external conflicts and, by extension, hurting the team.

External conflict takes place between two characters struggling to achieve their goals, so Nate’s external conflicts are always easy to see: He’s going to take down some greedy guy in a suit who’s victimizing innocent people. It’s good clear-cut conflict, no gray areas. Nate’s internal struggle is also pretty clear: He wants to see himself as in control, the mastermind, cool and focused, but when he comes up against the white collar crooks who remind him of Ian Blackpoole, the man who let his son die, all the rage and guilt he’s buried surges to the surface and overwhelms his illusion of rationality. Until he faces the fact that he’s out of control internally, he’s not going to be able to make the changes that will finally give him peace and a clear mind, the things he needs to protect his team and, not incidentally, to sober up. Because he can’t let go of his past, he’s jeopardizing his future and the future of the community he leads.

As “The Bottle Job” opens, the bar that’s become a second home to the team (their first home is upstairs in Nate’s apartment) is having a wake: its long-time owner has died, and his daughter, Cora, a red-head with a sweet face and a broken heart, is rousted by Evil Mark Doyle and his two Evil Henchmen, Liam and Liam’s brother. Cora’s father went to Doyle, a loan shark, to pay for her mother’s medical bills and put the bar up as collateral, now Doyle tells her she has two hours to pay him the $15,000 plus interest she owes him or the bar is his. Unfortunately for Doyle, Nate thinks of Cora as his niece, and Nate does not react well when the children in his family are threatened. He calls in the troops, they set up and run a wire con in an hour, and Nate wins the bar back. Yay, the day is saved!

Except that Nate’s running on internal conflict now, his guilt and rage at Ian Blackpoole transferred to Doyle, and he decides they’re going to take everything Doyle has, humiliate him, and destroy him. It’s an insane decision–Doyle’s dangerous and so are the thugs guarding the safe Nate sends Eliot and Parker to break into, they have no time because Doyle’s about to fly home to Ireland to tell his terrifying father that Boston is theirs for the taking, and most of all, they’ve already saved the client–but Nate can’t let it rest. He denies that it’s reckless, his common sense defeated by his thirst for vengeance.

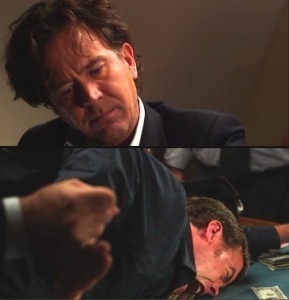

All of this is made much worse because, in order to make the wire con work, Nate had to drink with Doyle. Where in the first season he drank to dull the pain and rage, his sobriety this season has found him joining forces with this emotions, channeling them into torturing the marks beyond the call of duty. Nobody cares because the marks all deserve it, but now that Nate’s drinking again, it’s the worst of both worlds: he’s unleashed the anger and he’s drinking away his inhibitions, something made clear when he breaks Doyle’s finger after he’s been defeated. The finger-breaking isn’t part of the external conflict, that’s over; it’s evidence of the internal conflict, the honest man Nate thinks he is defeated by the raging sadist he’s become.

What does all of that have to do with community? It’s destroying it. In an earlier episode, Hardison says to Sophie, “We count on Nate to make the plan work, we count on you to take care of us.” But Nate’s plans are increasingly dangerous and ugly, and Sophie been driven away by Nate’s refusal to face his problems; she can’t face hers if she’s trying to keep him in check. So the other three team members draw closer together and watch Nate carefully: they’re still a family, but Dad’s a mean drunk and Mom’s on speed-dial, not there with them, so they have to watch each other’s backs. The place that’s supposed to their haven–their family–has become the most dangerous place to be.

This is an incredibly risky thing to do on a show that’s built on community. It’s brilliant character work, showing a man disintegrating from his internal conflict played out in external conflict, but it undermines the thing that brings the audience to the show: They want to see a great team in action–competence porn–that is also an emotionally bonded family. When the bonds of the community break, the bonds of the audience to that community weaken, too.

This has happened on two different shows aired this year. The first, Person of Interest, killed off a major character, the heart of the Machine Gang, and the team disintegrated because of it, one of the most important members quitting because he couldn’t save her. Losing and then bringing that team member back became the focus of several episodes as the PoI writers took a potentially damaging story line and used it to strengthen the community by showing the community dealing with its grief and then rebuilding itself. (The scene where Reese tells Finch he’s going to need a new suit and Finch realizes he’s coming back is one of my favorite scenes of the entire series; the look on Michael Emerson’s face is so poignant that you know exactly how much Reese and the Machine Gang mean to him.)

The other show is Arrow, a story with multiple subplots anchored by a central team of three. The Leverage producers have talked about their assumption that people tuned in for the cons, only to find out that scenes that viewers liked best were the five team members together in a room, interacting. I think Arrow was much the same: as long as all those insane, soapy subplots were anchored by three sane people in an underground lair figuring out how to stop crime, the show worked. When the writers moved away from the central three, playing the majority of plot points with people outside the team and drawing the protagonist away from his two partners, the show lost its center, and for some viewers, that’s resulted in a loss of faith in the authority in the text; that is, they don’t think the writers see what’s happening as a problem within the world of the story.

I think the key to any move that hurts a central team is in making it clear that the damage to the team is the result of internal conflict–the protagonist who lets his demons overwhelm his rationality and weaken the team–and that the story knows that’s a bad thing. The Leverage writers demonstrated over and over again that Nate’s detachment from the team was trouble, that he was going to hit bottom, and that the team was suffering from it. The Person of Interest writers showed Reese unraveling from his crisis of conscience over more than one episode, and then showed how the Machine and Finch brought him back. In both cases, viewers were uncomfortable but they stuck because it was clear that the writers understood that the disintegration of the team was a disaster, and they trusted the writers to fix it. The problem with Arrow is that it’s fairly clear that no one within the story thinks Oliver’s detachment from the central three is a bad thing, no indication that Oliver will pay for distancing himself from the team. In fact, Oliver’s hypocrisy and occasional outright stupidity is rewarded within the story. Two of the shows used the protagonist’s internal conflict to break down and then rebuild a stronger community through adversity, one presents its problematical protagonist and its community breakdown as story-as-usual and therefore not adversity.

I think it’s easy to look at external conflict and internal conflict as aspects of character alone, much harder to look at those conflicts as interlocked with everything else in the story. A story based only on internal conflict is boring and self-indulgent; a story based only on external conflict is shallow and insipid. A story whose external conflict is powered at least in part by its characters’ internal struggles not only adds depth and layers, it gives writers more leeway to do dangerous things in the story before pulling the narrative back from the edge.

Which is why next week we’re watching “The Three Strikes Job” and “The Maltese Falcon Job”: To watch Nate Ford hit bottom, resolve that internal conflict, and save the team he’s almost destroyed.