Reading With Eyes Shut: Kick Up Your Narrations

I don’t like my voice. It is to high. I sound too young. Thinking back, my voice must have been in its most formative stage when I taught kindergarten. Now, despite fifteen years of university-level teaching and a lifetime of interacting with adults, I still tend to sound like I am speaking to five-year olds.

How do I know this? Digital voice recorder. I set up a rudimentary recording studio for a prototype of the mixed media Reading with Eyes Shut edition of the Edison Jones adventure, Dead Chest Island. What came out was not at all satisfactory. Yet, it pointed out my faults.

By studying my recordings, I was able to pinpoint several problems that were fixable. My voice is still not the caliber of professional voice talent, but it sounds more pleasant—when I remember to monitor it. With practice, my “good” voice might become natural. Right now, I have to keep reminding myself “fatten your inflection, and pitch down instead of up.”

Okay, so what is the relevance for Reading With Eyes Shut? First, you don’t have to worry about it. If you are a parent, librarian, or teacher who is reading to students, don’t worry about your voice, and don’t let your voice discourage you. BUT, if you have a little time and you want to improve your narrations (making the stories you narrate a bit more interesting, perhaps), then make a quick recording of your voice, listen back, and see if the tips that follow here might help you improve.

Breathe. When you take a breath, you create a quiet space, which offers listeners a chance to consolidate their thoughts and build visual images. Take a breath at the end of every sentence. Commas also indicate breathing spaces. Use them.

Speak from your diaphragm. This advice is given by every voice coach, but what does it mean? Try this:

Hold your nose and say “Let’s go to the zoo.”

Let go of your nose and touch your cheek. Say “Let’s go to the zoo” again.

Touch your chest and say the phrase again.

Be sure you are sitting up straight (or standing) and put your palm just under your navel. Say, “Let’s go to the zoo” one more time. This last time, your voice should be a bit deeper and more mellow. That is diaphragmatic voicing.

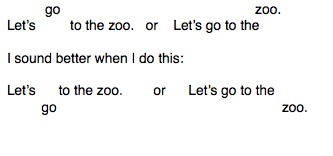

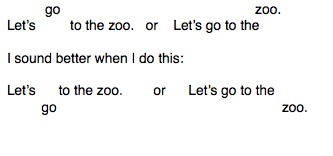

Monitor your inflection. My initial voice recordings made it clear that I tended to raise the pitch of my voice on syllables or words that I wanted to emphasize. If my speech was on a musical score, those would be high notes, indicating that my pitch as going “up” for emphasis. Because my voice is already in the high range, this additional “up-ness” made me sound shrill. I’ve been practicing moving my pitch “down” when I want to emphasize some passage.

Here’s what I tend to do:

Some voices have the opposite problem; they are too flat. To solve this problem, practice raising the pitch of your voice on some syllables.

Monitor your pace. Do not speak too quickly or too slowly. Change your pace as you read. For exciting parts of a story, pick up the pace. But, you can add an element of surprise by suddenly slowing the pace just before the climax of the action.

Monitor your volume. Obviously, you’ll adjust your speaking volume based on the setting in which you are reading. Bedtime reading calls for a quieter voice than a teacher might use to read to a class. But volume is a powerful narrative tool. Contrary to our intuition, a quiet voice will make your audience pay close attention. If you sense that you are loosing your audience—when children go all squirmy or their eyes begin to wander—start to whisper, and you’ll get their attention back.

Articulate. There’s a scene from the movie Six Degrees of Separation when Trent (Anthony Michael Hall) is instructing Paul (Will Smith) how to sound “classy.” The key was how to pronounce the word “bottle.” Trent says:

“This is the way you must speak. Hear my accent. Hear my voice. Never say you're going horse back riding. You say You're going Riding. And don't say couch. Say sofa. And you say Bodd-ill. It's bottle. Say bottle of beer.”

Before that movie, I never realized how we mash up English. Yep, I was even worse than Paul, slurring out “bodd ull” even when stone sober. It is “BOT ell” not “BODD ull.” Does it matter? Well, when children follow along in the book as you narrate, they might be confused when you read a word like “bottle” because they see the “t”s but hear “d”s. English has enough exceptions to spelling rules that we don’t have to create additional confusion by lazy pronunciation. So keep your lips moving crisply as you narrate. “Spit spot” as Mary Poppins would say. In fact, saying “spit spot” is good articulation practice.

So, have fun with these tips. Experiment with your narrative voice. It can add a fun dimension to your read aloud time.

How do I know this? Digital voice recorder. I set up a rudimentary recording studio for a prototype of the mixed media Reading with Eyes Shut edition of the Edison Jones adventure, Dead Chest Island. What came out was not at all satisfactory. Yet, it pointed out my faults.

By studying my recordings, I was able to pinpoint several problems that were fixable. My voice is still not the caliber of professional voice talent, but it sounds more pleasant—when I remember to monitor it. With practice, my “good” voice might become natural. Right now, I have to keep reminding myself “fatten your inflection, and pitch down instead of up.”

Okay, so what is the relevance for Reading With Eyes Shut? First, you don’t have to worry about it. If you are a parent, librarian, or teacher who is reading to students, don’t worry about your voice, and don’t let your voice discourage you. BUT, if you have a little time and you want to improve your narrations (making the stories you narrate a bit more interesting, perhaps), then make a quick recording of your voice, listen back, and see if the tips that follow here might help you improve.

Breathe. When you take a breath, you create a quiet space, which offers listeners a chance to consolidate their thoughts and build visual images. Take a breath at the end of every sentence. Commas also indicate breathing spaces. Use them.

Speak from your diaphragm. This advice is given by every voice coach, but what does it mean? Try this:

Hold your nose and say “Let’s go to the zoo.”

Let go of your nose and touch your cheek. Say “Let’s go to the zoo” again.

Touch your chest and say the phrase again.

Be sure you are sitting up straight (or standing) and put your palm just under your navel. Say, “Let’s go to the zoo” one more time. This last time, your voice should be a bit deeper and more mellow. That is diaphragmatic voicing.

Monitor your inflection. My initial voice recordings made it clear that I tended to raise the pitch of my voice on syllables or words that I wanted to emphasize. If my speech was on a musical score, those would be high notes, indicating that my pitch as going “up” for emphasis. Because my voice is already in the high range, this additional “up-ness” made me sound shrill. I’ve been practicing moving my pitch “down” when I want to emphasize some passage.

Here’s what I tend to do:

Some voices have the opposite problem; they are too flat. To solve this problem, practice raising the pitch of your voice on some syllables.

Monitor your pace. Do not speak too quickly or too slowly. Change your pace as you read. For exciting parts of a story, pick up the pace. But, you can add an element of surprise by suddenly slowing the pace just before the climax of the action.

Monitor your volume. Obviously, you’ll adjust your speaking volume based on the setting in which you are reading. Bedtime reading calls for a quieter voice than a teacher might use to read to a class. But volume is a powerful narrative tool. Contrary to our intuition, a quiet voice will make your audience pay close attention. If you sense that you are loosing your audience—when children go all squirmy or their eyes begin to wander—start to whisper, and you’ll get their attention back.

Articulate. There’s a scene from the movie Six Degrees of Separation when Trent (Anthony Michael Hall) is instructing Paul (Will Smith) how to sound “classy.” The key was how to pronounce the word “bottle.” Trent says:

“This is the way you must speak. Hear my accent. Hear my voice. Never say you're going horse back riding. You say You're going Riding. And don't say couch. Say sofa. And you say Bodd-ill. It's bottle. Say bottle of beer.”

Before that movie, I never realized how we mash up English. Yep, I was even worse than Paul, slurring out “bodd ull” even when stone sober. It is “BOT ell” not “BODD ull.” Does it matter? Well, when children follow along in the book as you narrate, they might be confused when you read a word like “bottle” because they see the “t”s but hear “d”s. English has enough exceptions to spelling rules that we don’t have to create additional confusion by lazy pronunciation. So keep your lips moving crisply as you narrate. “Spit spot” as Mary Poppins would say. In fact, saying “spit spot” is good articulation practice.

So, have fun with these tips. Experiment with your narrative voice. It can add a fun dimension to your read aloud time.

Published on March 25, 2014 09:23

•

Tags:

bedtime-stories, edison-jones, read-aloud, reading-with-eyes-shut, reluctant-readers

No comments have been added yet.

Reading With Eyes Shut

Reluctant readers may spend so much effort decoding words, that they have no additional mental capacity for imagery. Because decoding is “hard” and without imagery, there is little pleasure in reading

Reluctant readers may spend so much effort decoding words, that they have no additional mental capacity for imagery. Because decoding is “hard” and without imagery, there is little pleasure in reading, reluctant readers are trapped in a vicious cycle; they are not motivated by pleasure to develop their decoding skills, yet until they can easily decode the words on a page, they’ll not be able to experience the pleasure of reading. Reading With Eyes Shut is a collection of techniques for parents, teachers, authors, narrators, and librarians to help reluctant readers develop imagery and visualization shills.

...more

- J.J. Parsons's profile

- 4 followers