119. Exiles in New York, part 1

This post and the next are about exiles in New York City. Some of them chose to live here, others couldn’t wait until conditions – usually political – changed, permitting them to return to their homeland. Some learned English, others did not. Some loved New York, some tolerated it, and some were never comfortable here and got away as soon as they could. Admittedly, for most foreigners, New York requires an adjustment, being fiercely modern, fast-paced, noisy, and congested. On the other hand, it has been the preferred destination of many who were separated from the land of their birth.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

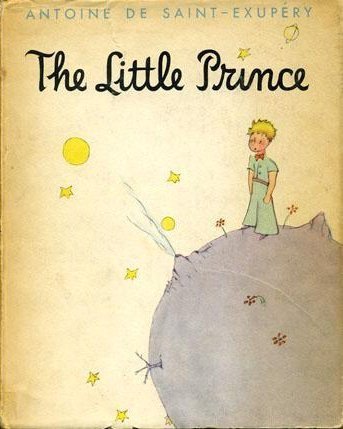

Saint-Exupéry in Toulouse in 1933. A renowned author and pioneer commercial aviator, Saint-Exupéry came to New York on the last day of 1940, not wishing to live under the Nazi-allied Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain, which had come to power following the disastrous French military defeat and collapse. He spoke no English, but French-speaking American friends fed and feted him and found him and his wife Consuelo, who had followed him here, twin penthouse apartments on Central Park South. (A very posh address. It pays to have friends with connections.) When one of those friends saw a figure in his doodles, she suggested that he turn it into the protagonist of a children’s book. This would be a radical departure for Saint-Exupéry, the author of serious and sensitive works about aviation and travel, but the idea took hold and he started writing what would become his best-known work, Le Petit Prince, an illustrated children’s book to be read as well by adults.

Saint-Exupéry in Toulouse in 1933. A renowned author and pioneer commercial aviator, Saint-Exupéry came to New York on the last day of 1940, not wishing to live under the Nazi-allied Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain, which had come to power following the disastrous French military defeat and collapse. He spoke no English, but French-speaking American friends fed and feted him and found him and his wife Consuelo, who had followed him here, twin penthouse apartments on Central Park South. (A very posh address. It pays to have friends with connections.) When one of those friends saw a figure in his doodles, she suggested that he turn it into the protagonist of a children’s book. This would be a radical departure for Saint-Exupéry, the author of serious and sensitive works about aviation and travel, but the idea took hold and he started writing what would become his best-known work, Le Petit Prince, an illustrated children’s book to be read as well by adults. Another American friend, Silvia Hamilton, saw him regularly for a year and encouraged him in his writing until at last, in April 1943, the manuscript was finished. Rushing off to rejoin the Free French Air Force in North Africa, the author tossed a rumpled paper bag onto Hamilton’s entry table, containing the 140-page draft manuscript and drawings, the pages replete with corrections as well as coffee stains and cigarette burns. The finished work has been called fabulistic, abstract, ethereal; it is anything but realistic and makes no direct reference at all to the war in progress. In it a pilot stranded in a desert meets a yellow-scarfed young prince fallen to earth from a tiny asteroid. The prince tells of visiting various asteroids and describes the inhabitants of each: a king who thinks he rules the entire universe; a businessman counting the stars he thinks he owns; a drunk who drinks out of shame at his drinking; and so on. “Grown-ups are so strange,” says the prince.

Another American friend, Silvia Hamilton, saw him regularly for a year and encouraged him in his writing until at last, in April 1943, the manuscript was finished. Rushing off to rejoin the Free French Air Force in North Africa, the author tossed a rumpled paper bag onto Hamilton’s entry table, containing the 140-page draft manuscript and drawings, the pages replete with corrections as well as coffee stains and cigarette burns. The finished work has been called fabulistic, abstract, ethereal; it is anything but realistic and makes no direct reference at all to the war in progress. In it a pilot stranded in a desert meets a yellow-scarfed young prince fallen to earth from a tiny asteroid. The prince tells of visiting various asteroids and describes the inhabitants of each: a king who thinks he rules the entire universe; a businessman counting the stars he thinks he owns; a drunk who drinks out of shame at his drinking; and so on. “Grown-ups are so strange,” says the prince.Published in New York in French and English in 1943, Le Petit Prince was Saint-Exupéry’s last work. Though he was really too old, the Free French let him fly. While on a reconnaissance flight on July 31, 1944, his plane disappeared in the Mediterranean, presumably shot down by a German plane. The plane’s wreckage was found only sixty years later, though his silver identity bracelet was discovered snagged in a fishing net off Marseilles in 1998. Meanwhile Le Petit Prince, not published in France until 1946, has been translated into 250 languages and sells over 1.8 million copies a year. The author’s self-imposed exile in New York was fruitful in the extreme. I urge anyone who hasn’t read the work to do so; it is charming, provocative, unique. In fact, I recommend all his works, especially Terre des hommes (in English, Wind, Sand, and Stars, though I prefer the French title by far).

André Breton

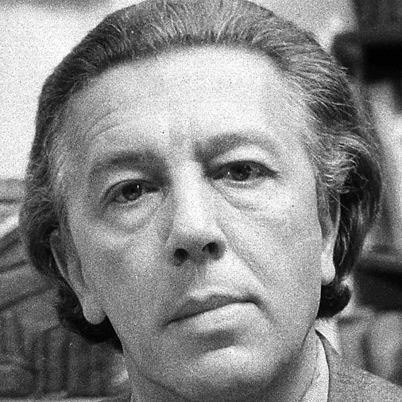

The rise of fascism in Europe and the outbreak of World War II brought many European artists and intellectuals to these shores, many of them to New York. “Tête léonine,” said a fellow graduate student at Columbia, when I mentioned the poet André Breton as a possible dissertation subject, and it’s true that Breton usually wore his hair fairly long, giving him a somewhat lionlike appearance. The founder and arbiter of Surrealism, Breton was drafted into the army in 1939 and demobilized following the French defeat in 1940. No friend of Vichy, he left his beloved Paris for Marseilles, and from there by boat in 1941 managed to reach Martinique, where the Vichy authorities informed him that there was no need for Surrealism in Martinique, and interned him for a while. Released, he then managed to reach New York, where he found many of his Surrealist comrades, founded the Surrealist review VVV, and with Marcel Duchamp organized a Surrealist exhibition. He evidently supported himself by taking a broadcasting job, probably one related to the war effort, even though, like Saint-Exupéry, he never bothered to learn English or, so far as I know, any foreign language. An intellectual for whom ideas were vital entities to espouse and fight for, he exuded as always an undeniable charisma that drew others to him, and a quarrelsome streak that drove some away. No opinion of his was tepid or wishy-washy; a celebrant of heterosexual love and the surreal, he was determinedly anticlerical and fiercely homophobic.

Though he had long since broken with the Communist Party, where he never felt at home, in New York he had yet to renounce the tenets of dialectical materialism. Knowing this, the art critic Meyer Schapiro invited two intellectuals of his acquaintance, one a dedicated Marxist and the other a critic of Marxism, to a debate for Breton’s benefit. During the debate Breton listened intently but said not a word, as the critic of Marxism gained the upper hand. After that, Schapiro told me long ago, André Breton never again mentioned dialectical materialism. His distancing from Communism and its tenets was complete and final.

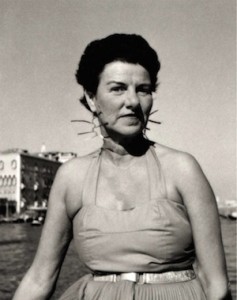

Wearing Alexander Calder earrings. Hosting Breton and other exiles in New York was the wealthy art patron Peggy Guggenheim, a niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, founder of the museum that bears his name. She had taken an active interest in Surrealism in the 1930s and in a very short time amassed a significant collection. Now, on West 57thStreet in wartime New York, she opened a museum/gallery called The Art of This Century Gallery, of which only the front room was a commercial gallery. She was married at the time to the Surrealist artist Max Ernst, who found the marriage a convenient way to gain entry to the U.S., but by her own admission she had a sexual appetite for men that matched her appetite for art. Photographs reveal a woman neither plain nor memorably beautiful, but she had money and influence and chutzpah (she was, after all, Jewish), and many an artist enhanced his career by obliging her in this regard. A 1942 photograph taken in her New York apartment shows herself posing with no less than fourteen renowned artists of the time – not all of them necessarily her lovers – including Breton, Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian. It is a curious photograph, with some of the subjects facing right, some left, and only a few looking squarely at the camera. Only Peggy Guggenheim could have assembled in one spot such a clutch of avant-garde talent, most of them in wartime exile.

Wearing Alexander Calder earrings. Hosting Breton and other exiles in New York was the wealthy art patron Peggy Guggenheim, a niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, founder of the museum that bears his name. She had taken an active interest in Surrealism in the 1930s and in a very short time amassed a significant collection. Now, on West 57thStreet in wartime New York, she opened a museum/gallery called The Art of This Century Gallery, of which only the front room was a commercial gallery. She was married at the time to the Surrealist artist Max Ernst, who found the marriage a convenient way to gain entry to the U.S., but by her own admission she had a sexual appetite for men that matched her appetite for art. Photographs reveal a woman neither plain nor memorably beautiful, but she had money and influence and chutzpah (she was, after all, Jewish), and many an artist enhanced his career by obliging her in this regard. A 1942 photograph taken in her New York apartment shows herself posing with no less than fourteen renowned artists of the time – not all of them necessarily her lovers – including Breton, Ernst, Leonora Carrington, Fernand Léger, Marcel Duchamp, and Piet Mondrian. It is a curious photograph, with some of the subjects facing right, some left, and only a few looking squarely at the camera. Only Peggy Guggenheim could have assembled in one spot such a clutch of avant-garde talent, most of them in wartime exile. Front row: Leonora Carrington, 2nd from left. Middle row: Max Ernst, far left; Breton in

Front row: Leonora Carrington, 2nd from left. Middle row: Max Ernst, far left; Breton inmiddle; Fernand Léger, 2nd from right. Back row: Peggy Guggenheim, 2nd from left;

Marcel Duchamp, 2nd from right; Piet Mondrian, far right. It was not Peggy Guggenheim who enlisted Breton’s affections in New York, but Elisa Claro (née Bindorff), whom he met in a French restaurant on 56thStreet in 1943 and married in (of all places!) Reno, Nevada, in 1945, she becoming his third and final wife. He traveled with her to Canada in 1944, and the following year they visited the Hopi reservation in Arizona, where they observed Hopi rituals and Breton added kachina dolls to his art collection. Accompanied by Elisa, in the spring of 1946 Breton returned to Paris to resume his Surrealist activities and rambunctious ways, as inclined as ever to provocation and controversy. His former Surrealist comrades Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon, now ardent Communists, dismissed him as irrelevant, since he had not participated, as they had, in the Resistance. Which didn’t prevent him from advancing as always the Surrealist cause and exploring what he would term Magical Art.

W. H. Auden

Auden in 1939. The English poet and man of letters W. H. Auden, already well known in England as a leftist writer and intellectual, came to New York in January 1939 with his friend the writer Christopher Isherwood, the two of them entering the U.S. with temporary visas but intending to stay. Auden and Isherwood, age 32 and 35 respectively, had known each other since boarding school, and in the 1920s had left strait-laced, homophobic England for the freedom of Weimar Berlin. There Auden had remained for nine months and Isherwood for years, the chief attraction being a seemingly inexhaustible supply of boys available and eager for sex. In the 1930s Auden worked in England as a schoolteacher, essayist, reviewer, and lecturer, but in 1937, when he did volunteer work for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, he became disillusioned with politics and disgusted with war. It was this experience, above all, that prompted him to quit England for America, where he hoped to resolve the doubts, both political and personal, now plaguing him.

Auden in 1939. The English poet and man of letters W. H. Auden, already well known in England as a leftist writer and intellectual, came to New York in January 1939 with his friend the writer Christopher Isherwood, the two of them entering the U.S. with temporary visas but intending to stay. Auden and Isherwood, age 32 and 35 respectively, had known each other since boarding school, and in the 1920s had left strait-laced, homophobic England for the freedom of Weimar Berlin. There Auden had remained for nine months and Isherwood for years, the chief attraction being a seemingly inexhaustible supply of boys available and eager for sex. In the 1930s Auden worked in England as a schoolteacher, essayist, reviewer, and lecturer, but in 1937, when he did volunteer work for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War, he became disillusioned with politics and disgusted with war. It was this experience, above all, that prompted him to quit England for America, where he hoped to resolve the doubts, both political and personal, now plaguing him. Chester Kallman

Chester KallmanWhen the two newly arrived English writers gave a reading here, two college students from Brooklyn College sat in the front row and winked and smiled provocatively. One of them, Chester Kallman, showed up at their lodgings the next day to interview them for the college newspaper, causing Auden to remark sourly, “It’s the wrong blond!” But Kallman, with an ample supply of Brooklyn chutzpah, persisted with the interview, and by the end of it Auden’s interest had kindled. In fact, he was smitten; they soon became lovers.

The New York literary scene was to Auden’s liking and he remained here, but in April 1939 Isherwood, sensing that the East Coast would be Auden’s turf, went to California, where he would settle down and cultivate the West Coast as his own. When war broke out in September, Auden informed the British Embassy in Washington that he would return to Britain, if needed, but was told that for his age group only qualified personnel were wanted. In spite of this, there would develop considerable resentment in Britain that Auden and Isherwood had absented themselves when Britain, following the fall of France, stood alone against Germany and endured the horrors of the Blitz. Auden, on the other hand, viewed the wartime sloganeering, speechifying, and committee-joining fervor of British intellectuals as irrelevant to the war effort, and as potentially damaging as fascism at its worst.

In 1940-41 Auden lived in a ramshackle brownstone at 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights in an experiment in communal living launched by his friend George Davis, a brilliant fiction editor recently fired from his job at Harper’s Bazaar because of his total lack of self-discipline. Experiments in communal living were nothing new in America, but nineteenth-century endeavors had proven impractical, since the free spirits involved were better at talk and philosophizing than at managing money, doing the dishes, and taking out the trash. Nothing daunted, Davis assembled in the brownstone on Middagh Street a number of his authors and acquaintances, including Auden, Carson McCullers, Benjamin Britten and his partner Peter Pears, Jane and Paul Bowles, Gypsy Rose Lee, and others – such a concentration of creative talent, seasoned by the presence of an acclaimed stripper recently turned author, that it spices the mind.

Carson McCullers Auden was not noted for neatness – wherever he lived, he left papers and cigarette ashes strewn about – but in this crowd he was by contrast the perfect bourgeois, imposing regular meals and regular working hours for all. He wrote out cooking and cleaning schedules, lectured his housemates when they used too much toilet paper, and announced at dinnertime, “There will be no political discussion.” He and Carson McCullers, who had just achieved literary fame with the publication of her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, developed a warm teacher-student friendship beneficial to both – a remarkable achievement, given Cullers’s neurotic hang-ups and hard drinking. At Davis’s invitation Gypsy Rose Lee joined the party so he could help her work on a novel, The G-String Murders, which in time became a best-selling mystery. She alone of the residents had both money and common sense. Her maid came with her but was unable to cope with the accumulated dirty clothes and dishes, empty bottles, and cigarette ashes and stubs.

Carson McCullers Auden was not noted for neatness – wherever he lived, he left papers and cigarette ashes strewn about – but in this crowd he was by contrast the perfect bourgeois, imposing regular meals and regular working hours for all. He wrote out cooking and cleaning schedules, lectured his housemates when they used too much toilet paper, and announced at dinnertime, “There will be no political discussion.” He and Carson McCullers, who had just achieved literary fame with the publication of her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, developed a warm teacher-student friendship beneficial to both – a remarkable achievement, given Cullers’s neurotic hang-ups and hard drinking. At Davis’s invitation Gypsy Rose Lee joined the party so he could help her work on a novel, The G-String Murders, which in time became a best-selling mystery. She alone of the residents had both money and common sense. Her maid came with her but was unable to cope with the accumulated dirty clothes and dishes, empty bottles, and cigarette ashes and stubs. Visiting this curious artists colony were Anais Nin, who christened the brownstone the February House because several of the occupants had birthdays in February, and Thomas Mann’s daughter Erika and son Klaus. (Auden had married Erika to give her a British passport, but by mutual consent the marriage was never consummated and they lived apart.) The novelist Richard Wright and others also dropped in.

Amazingly, the residents of the February House all managed to get some significant work done, but their love life was often less than satisfactory. George Davis happily cruised the Brooklyn piers, but Carson McCullers pined futilely for the Swiss journalist and world traveler Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach, a friend of the Manns, while Auden yearned stubbornly for Chester Kallman, who after two years, being young and adventurous, informed Auden that from now on he would range freely in search of sex. Deeply wounded, Auden, who wanted a stable relationship, managed to maintain his friendship, albeit sexless, with Chester. Auden’s friends never could grasp why Auden clung to a younger partner whom they considered in every way his inferior, but they apparently failed to grasp that desire is not wise or prudent or practical; it simply is. Auden and Chester Kallman each offered the other something that he needed, something beyond sex; the relationship ended only with Auden’s death. How Auden squared his sex life with the Anglican faith he had returned to in 1940 I do not know. He seems to have been troubled by his sexuality, as Kallman was not.

Inevitably, communal living in the February House began to fray on the nerves of the participants. Fed up with her housemates’ drinking and slovenliness, Gypsy bowed out first, soon followed by McCullers, whose boozing and late hours had impaired her fragile health. Irked by Paul Bowles’s noisy sex games with his wife and loud partying, Auden and Britten expelled the offender, but Britten and Pears then also left the house and America, returning to wartime Britain. Soon afterward Auden too moved out, convinced of the need for a balance between bohemian chaos and bourgeois convention that the February House obviously could not provide. George Davis stayed stubbornly on until the house was demolished in 1945; in time he would marry Kurt Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, and work hard promoting Weill’s work. The story of 7 Middagh Street, Brooklyn Heights, brief but stellar, has justifiably been called a true mingling of the sublime and the ridiculous; it is well told in Sherill Tippins’s February House (Houghton Mifflin, 2005).

When Auden was called up for the draft in 1942, the U.S. Army rejected him because of his avowed homosexuality. For several years he taught at Swarthmore College and in 1945, unknown to Auden at the time, he was considered for the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on the basis of his volume For the Time Being, but lost out to Karl Schapiro because of his alleged Communism (he had never joined he Party) and his aloofness from the war. Then, in March 1945, he applied to join U.S. Army as part of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany, and became a major as a “bombing research analyst in the Morale Division,” interviewing civilians in the devastated cities of Germany. Significantly, neither his wartime disgust with war nor his homosexuality seems to have been a problem, and the prospect of a steady and substantial salary was surely an enticement. The thought of Auden in uniform is, to put it mildly, arresting. (The Strategic Bombing Survey, by the way, studied the effects of bombing on both Germany and Japan and concluded that 10% of the bombs hit their target. One wonders, then, where the other 90% ended up.)

The later Auden. Auden became a U.S. citizen in 1946 and continued to live in New York, making a living as a writer, teacher, lecturer, and librettist. Reading his poetry, he practiced a low-keyed delivery, despising the sonorous and inflated tones that often plague poets when they read. In 1948 his long poem The Age of Anxiety won the Pulitzer Prize. From 1953 on he shared houses and apartments with Kallman, though later he would summer in Europe. Time took its toll on both of them. Auden’s aging face grew fissured from his steady smoking, and svelte, young Chester became a middle-aged man who drank far more than was good for him. When Stravinsky asked Auden to do the libretto for The Rake’s Progress, Auden, hoping to reclaim Chester through the steadiness of work, enlisted his support and sold him to the composer as a collaborator. Occasionally Kallman would show some poetry of his own to a friend, who was invariably struck by its intensity. One suspects that Kallman secretly resented being in the shadow of an acclaimed man of letters, but he published three volumes of his own poetry and in collaboration with Auden became known as a librettist.

The later Auden. Auden became a U.S. citizen in 1946 and continued to live in New York, making a living as a writer, teacher, lecturer, and librettist. Reading his poetry, he practiced a low-keyed delivery, despising the sonorous and inflated tones that often plague poets when they read. In 1948 his long poem The Age of Anxiety won the Pulitzer Prize. From 1953 on he shared houses and apartments with Kallman, though later he would summer in Europe. Time took its toll on both of them. Auden’s aging face grew fissured from his steady smoking, and svelte, young Chester became a middle-aged man who drank far more than was good for him. When Stravinsky asked Auden to do the libretto for The Rake’s Progress, Auden, hoping to reclaim Chester through the steadiness of work, enlisted his support and sold him to the composer as a collaborator. Occasionally Kallman would show some poetry of his own to a friend, who was invariably struck by its intensity. One suspects that Kallman secretly resented being in the shadow of an acclaimed man of letters, but he published three volumes of his own poetry and in collaboration with Auden became known as a librettist. Auden’s literary reputation has had its ups and downs. While a poet friend of mine praised him to the skies, I found him a bit too ironic, detached, intellectual, preferring the Celtic word jungle of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, impenetrable as that jungle can be. By the time of his death in 1973, Auden was recognized as a literary elder statesman. He died in Vienna of heart failure and is buried in Kirchstettin, a town in Austria where he had owned a farmhouse.

Just as Auden once went to Berlin for boys, so Kallman went to Athens for the same, moving his winter home there in 1963. He is said to have been generous to his young male lovers. He died suddenly in Athens in 1975, age 54, and is buried there in the Jewish Cemetery, far apart from Auden. Some sources say that, mourning Auden, he died of a broken heart, but I find this fanciful. On a deep level his life was not a happy one, but perhaps I'm being judgmental.

A note on WBAI: The loyal staff, whose devotion is commendable, profess optimism about saving the station, but the desperate appeals for donations go on and on and on. I never thought the award-winning news program would vanish, but it did. The substitute news program likewise vanished, replaced by fund-raising specials, then came back, and now has vanished again. Inconsistency in programming is sure to drive listeners away -- listeners like me, a longtime supporter of the station. I hear Gary Null’s one-hour program at noon on weekdays, though he warns that he may be eliminated, because of his criticism of the current management. I hear Richard Wolff’s weekly economics program at noon on Saturday, though I’ve got his message fully by now (capitalism is bad, socialism is the answer). And I hear Thom Hartmann’s 5 p.m. program weekdays, though his self-promotion annoys me, as does his constant replaying of segments, often up to three or four times within two days. But that’s it. I find it very easy to turn from WBAI to WNYC, and that is the crux of the problem. (Apologies to those unfamiliar with WBAI and its travails, but I feel a need to chronicle its endless downward spiral; unique, it is in danger of disappearing forever.)

This is New York

Bob Jagendorf

Bob JagendorfComing soon: Exiles in New York, part 2. The Scarlet Sisters, a Dragon Lady, an anarchist with a compact, diverse others.

© 2014 Clifford Browder

Published on March 23, 2014 05:17

No comments have been added yet.