How to Take Criticism Like a Pro

Image via Flickr Commons, courtesy of JonoMeuller

One of the greatest blessings of being an author and teacher is I meet so many tremendous people. I feel we writers have a unique profession. It isn’t at all uncommon to see a seasoned author take time out of a crushing schedule to offer help, guidance and support to those who need it. I know of many game-changers, mentors who transformed my writing and my character. Les Edgerton, Candace Havens, Bob Mayer, James Rollins, James Scott Bell, Allison Brennan are merely a few I can think of off the top of my head.

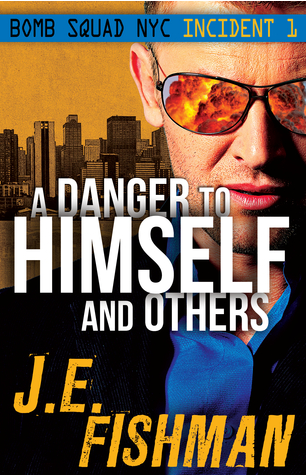

J.E. Fishman is another, and he offers a very unique perspective because he’s worked multiple sides of the industry. He was a former NYC literary agent, an editor for Doubleday and now he’s a novelist. His newest book A Danger to Himself and Others is masterfully written. I love books that make me pause, underline and dog-ear. As much as I think I know? I can always learn more. I make it a habit to study those who write better than I do.

Today, J.E. Fishman is here to offer some of the best advice any of us can get when we’re new. If we’ve been around for awhile, we can always use a refresher. Writers do work an emotional, often isolated job, and it’s easy to forget to chew with our mouths closed be professional when so many of us are writing from beneath a pile of laundry and toys.

I hope this guest post blesses you as much as it has me…

Take it away!

J.E. Fishman

We’re all amateurs at most things, but that’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Maybe we shoot hoops after work or set up an easel in retirement. Perhaps we cook on weekends or spend the morning making an iMovie production of our summer vacation. We are neither professional basketball players nor professional painters nor chefs nor directors. We’re just having fun.

But what if we’re trying to achieve something more as writers? How do we get out of the bush leagues and behave more professionally?

Let’s start by acknowledging that amateurs often have conflicting priorities. They may allow foolish dreams to captivate them, for example, but they can’t always invest the hard work necessary to achieve those dreams. They frequently lean on raw talent when the greater challenge requires practicing craft. And with regard to criticism, they often have thin skin.

I’d like to talk about the thin skin part.

In my experience, professionals are not easily satisfied by their own work, whereas amateur writers take a degree of pride in their work that’s often not commensurate with the accomplishment. And if the person doing the criticizing is not a fellow writer, fuhgetaboutit!

What do they know, the tyro author tells himself. Or, if he’s rude, he says aloud, “What do you know?”

But this defensiveness is a sign of weakness. More important, it turns self-improvement — which is difficult enough in the best of times — into an insurmountable challenge.

Sure, the professional writer who can communicate the technical deficiencies of our work is worth heeding if we seek to improve. But the casual observer’s opinion is just as valuable. After all, most of our audience are just plain old readers, not writers.

Here’s something worth remembering: If we’re creating art, we owe our audience something, not the other way around.

A professional knows this because a professional lives and dies with it. Her skin may be thick or thin by inclination, but she forces herself to respond in certain ways toward criticism because she understands the stakes. To disappoint one audience member is potentially to disappoint all of them.

I was struck last month by a Chuck Wendig blog post in which he called out independent authors, challenging them not to publish amateurishly (“slush pile on display” were his words) — urging them to behave with professionalism, which is to say, to respect their audience. It got me thinking of the people I’ve worked with over the years as an editor and an agent and an author. Over time, you come to know a pro as much by her process as by the work she produces.

Some people think pros just work harder than everyone else. While it’s true that they often do, there are any number of other ways in which a professional distinguishes herself. Acceptance of criticism is among the most powerful. If we want people to take us seriously as a writer, we must take criticism like a pro does:

A pro respects roles. Your editor may or may not be a writer herself. In any case, it isn’t her job to rewrite your novel (unless you hired her specifically to do that, of course). The pro knows where her responsibilities lie.

A pro separates the work from himself — He pushes ego out of it. Even if we’re writing something very personal, we are not our work. The work is a form of communication. It is not what we are, but what we say. The pro doesn’t internalize criticism.

A pro seeks opportunities to learn from criticism. She knows that her art is not static, that a failure to grow with the craft will harm the next work. Every work becomes imperfect the moment it seeks expression. To learn as we go is a means of approaching that ever-elusive perfection.

A pro looks for the source of the problem, not easy fixes. He understands whose job it is to seek solutions. Hint: not the reader’s. Say the reader points to a given scene and asks of the protagonist, “Why’d he do that?” The facile answer might be, “Well, that guy was pointing a gun at him.” The writer here is telling himself that he only needs to clarify about the gun. But in fact, he must ask himself whether he needs to clarify the deeper character of the protagonist that would lead him to choose the action that’s been questioned.

A pro hears what is not said. The amateur too easily dismisses criticism that’s not expressed in the framework of how we think about our own craft. But the pro reads between the lines, asking herself what in the story caused the reader to have that reaction.

A pro accepts challenges. Not every item of criticism calls for a response within the work, but the default should never be a shrug of the shoulders. The pro understands that the path of least resistance, while tempting, rarely leads to great execution.

A pro never argues, never rebuts. The work should be all we ever need to convince anyone of anything. It stands alone. The pro knows that her work will eventually go out into the world defenseless. If a proper understanding of the work requires an off-the-page argument from the author, it’s already failed for that particular reader. There’s no point in discussing it further except perhaps by asking questions to learn.

A pro doesn’t belittle the messenger. Imagine if only architects were allowed to have opinions about the beauty (or utility) of a house. Don’t ever put down critical readers, even in your own mind. Respect your audience, and out of that respect will grow the potential for greatness.

Finally, a pro knows that all the aspects I’ve outlined here are aspirational. None of us is perfect at them — certainly not me. At times I have sniffed at criticisms, failed to read between the lines, not risen to the challenge.

Let’s face it, pro or amateur, criticism of our work always stirs up a measure of disappointment. That’s why we must train ourselves to respond as the pros we claim to be or aspire to be. In the age of specialization, people have high standards for the work of others. We must have those same high standards for ourselves.

****

*Applause* Thanks, J.E. I know all of this is tough to do. We are all works in progress. I know I am.

What about you guys? Are you struggling with leaving the role of the amateur? Are you actively seeking ways to toughen your skin? Or have you gotten to the point where you welcome the crucible? Were you always that way? I know I stared crying in my car after critique. Now? A beta can chop my work to the ground, burn it and then nuke it and I don’t take it personally. I LOVE that someone would take the time to give my work the “trial by fire” before the reviewers can. But, I was NOT always this way. I still struggle to remain this way.

I LOVE hearing from you!

J.E. Fishman, a former Doubleday editor and literary agent, is author of the wisecracking mystery Cadaver Blues, as well as thrillers The Dark Pool and Primacy. His Bomb Squad NYC series of police thrillers launches this month with A Danger to Himself and Others and Death March.

To prove it and show my love, for the month of March, everyone who leaves a comment I will put your name in a hat. If you comment and link back to my blog on your blog, you get your name in the hat twice. What do you win? The unvarnished truth from yours truly. I will pick a winner once a month and it will be a critique of the first 20 pages of your novel, or your query letter, or your synopsis (5 pages or less).