FoW (11): Enhancing human performance

By Daniel P. Sukman

Best Defense Future

of War entrant

One of the primary elements of military research and

development is how to enhance human performance in combat, from better

equipment, weapons with longer reach, lighter loads to carry, better

physiological preparation, to all-encompassing physical enhancements. Today,

with advancements in science and technology, the U.S. military is at a crossroads

in determining how far to go in considering how to attain soldiers, airmen,

Marines, and sailors who can physically outperform our potential adversaries. To

borrow from the Olympic motto, the future of war will demand "faster, stronger,

and higher."

The limits of enhanced human performance needs to be where

the enhancements negatively effect a person the day after they leave the U.S.

Military. Although the military is a profession, unlike doctors and lawyers,

serving as a soldier does not encompass the entirety of adulthood. Most servicemembers

will leave service in their early twenties, and even those who put in 20-30

years of service will still depart with half a lifetime remaining on earth. The

complexity of the issue revolves around the argument that although certain

human enhancements may negatively affect your life after the service, it may

extend your life so you reach that point. Looking at the different ways we can

influence the human body to survive and win on future battlefields is the next

step in the evolution of the American way of war.

To meet the demands of the future battlefield, the means of

altering the human body and mind that we as a society should find acceptable

needs to be examined. To highlight the complexities, I offer the following

"lists of things" that enhance human performance, be it in the office, cockpit

or sports field. Think about what is considered "legal" what is "ethical" and

why.

Coffee, soda,

Snickers bars, amphetamines, Ritalin

Cold medicine, Human

Growth Hormone (HGH), performance enhancing drugs (PEDs), anabolic steroids,

pain killers

Vaccinations, Tommy

John surgery, Lasik eye surgery, Blood Doping/EPO, training at high altitude

As you look at each list, you can see a variety of methods,

be it ingestion of caffeine, or a surgery that physically alters your god-given

natural abilities. Some methods on the list are banned by the Olympics (cold

medication) and professional sports (deer antler spray) but remain legal for

the general populace, others are encouraged (Tommy John surgery), while others are

illegal to obtain on your own. Some of the items, such as coffee and soda, are

even banned by some religions due to the caffeine within those drinks.

An unspoken truth is that soldiers, like athletes, do not

have to be convinced to take performance enhancing drugs. Legions of staff

officers start their day with pots of coffee followed by the nicotine rush

contained in dip and other smokeless tobacco products. Similarly, the use of

drugs such as Ambien to promote sleep in stressful situations or when travelling

long distances is widely used in the armed forces. Pilots have a long history

of taking "no doze"-type pills and even amphetamines when required to fly long

distances. A "Red Team" member worth his salt would do well to find an

asymmetric way to limit coffee to staffs and energy drinks and dip to young

soldiers.

Sleep plans, or as those in the military call it "fatigue

management," is a vital part of any combat mission planning. In the 2012 Marine

Corps S&T Strategic Plan, planning for sleep is as vital as "planning for

food, fuel, ammunition or other essential logistical supplies." There may be a

risk of addiction that must be balanced, however, with the pharmaceutical

agents that exist to enhance the effectiveness of sleep during combat. If those

drugs enhance the decisions of leaders, or allow soldiers to operate at higher

altitudes, and if that, in turn, will save U.S. lives in battle, those methods

should be pursued.

In the sport of cycling, taking Erythropoietin (EPO)to raise

red blood cell counts, thus improving oxygen delivery to the muscles, is

officially banned (as Lance Armstrong is well aware of) but it is quite legal

to train at high altitude or sleep in a hyperbaric tent, which achieves exactly

the same result physiologically. Should the U.S. military, in preparation for

combat in places such as Afghanistan take EPO, or limit itself to train in

areas of high altitude? Why not allow soldiers in combat to take EPO if it will

enhance their performance and increase the odds of completing missions and coming

home alive?

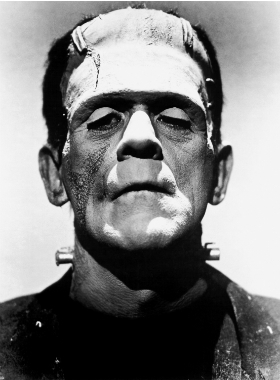

Aside from biological enhancements, actual physical changes

to servicemembers can be envisioned in the future. Today we are able to replace

lost limbs on our wounded warriors, but can we add to or change (permanently)

physical characteristics of our servicemembers to provide them with one-on-one

overmatch against potential adversaries? If we can change the skin composition

to be tougher and more resistant to bullets and shrapnel, should we do so? Of

course, as Patrick Lin noted in his article "Could

Human Enhancement Turn Soldiers into Weapons that Violate International Law? Yes" in

the January 2013 issue of The

Atlantic, doing so might embolden our adversaries to engage in harsher

tactics and procedures when fighting U.S. forces. Sleep deprivation may not

torture you if you physically don't require sleep.

Enhancements in human performance, be it physical or mental,

can occur long before it becomes a necessity due to a catastrophic injury

incurred in training or in combat. If technology would allow for soldiers to

have surgery to increase their running pace, or for a plate to be inserted into

the knees or back that makes a parachute landing fall easier, or carrying a 70

pound rucksack not all that difficult, why not perform that surgery "left of

the boom," so to speak.

Mental enhancements can be a necessity in the fast-paced

ever-changing complex world of combat. This complex world demands rapid

decision-making more often than not with imperfect information and

intelligence. Should the use of certain drugs to focus the attention of

decision makers (e.g. Ritalin) and better prepare forces for combat be

encouraged? I am not advocating making military leaders walking drug stores,

but if more focused mental preparation and planning of combat can save lives,

why not offer the best enhancements modern science can provide?

The question becomes, should servicemembers be required to

risk their long-term health in pursuit of short-term physical and mental

enhancements. Professional athletes are largely prohibited from doing this, hence

the ban on PEDs and anabolic steroids. However, soldiers, Marines, airmen, and

sailors are expected as part of their service to put both their health and

lives at risk. As Clausewitz wrote,

war is violence." The future of warfare will require stronger, faster soldiers

who have more endurance; however we must be careful not create a new generation

of East German Olympic swimmers.

As the science and technology of warfare continues to

proliferate around the world, the assumption should be made that adversaries of

the United States and our allies and partners will not limit themselves with

ethical considerations in how they enhance the performance of their

footsoldiers. U.S. soldiers will not go into combat high on khat, but should

acknowledge that certain adversaries in Africa may be as we saw in Task Force

Ranger in 1993. Performance enhancing drugs, stimulants, and other narcotics

will certainly be used by our adversaries, and we should develop training and

strategy that accounts for this. We must also prepare for adversaries who have

access to advanced technologies who may use nanotechnology, or even

pharmaceuticals such as Adderall to increase their cognitive performance.

Risk of each human enhancement must be a paramount factor in

considering what we can do with servicemembers. For example, steroids can cause

terrible health problems, like liver and kidney failure, while the risks of eye

surgery are much lower both in terms of probabilities and effects. By this

standard, we accept greater risk in the now, in that performance will be

reduced in warfare; however the risk is greater of catastrophic injury or death

when involved in combat operations.

What side of the risk coin

should we as a military profession find easier to accept?

Major Daniel Sukman, U.S. Army, is a strategist at the Army

Capabilities Integration Center, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command at

Fort Eustis, Virginia. He holds a B.A. from Norwich University and an M.A. from

Webster University. During his career, MAJ Sukman served with the 101st

Airborne Division (Air Assault) and United States European Command. His combat

experience includes three combat tours in Iraq. This

article represents the author's views and not necessarily the views of the U.S.

Army or Department of Defense.

Tom note: Got your own views of the future of war?

Consider submitting an essay

. The contest remains open for at least another few weeks. Try to keep it

short -- no more than 750 words, if possible. And please, no footnotes or

recycled war college papers.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers