The Wonderful Rule of 3

By Natascha Biebow

All good things come in threes (and bad things, too). Why? It seems that three is the smallest number needed to create a pattern; it makes stories more satisfying and funnier. Plus everyone knows that stories must have three elements: a beginning middle and end.

From early on, children are preconditioned to expect this pattern:

The rhythm of the day has three parts – morning, noon and night –

and three meals too – breakfast, lunch and tea.The rhythm of growing has three stages: baby, child and teen.Most of the lullabies, songs and nursery rhymes told and sung from babyhood are built upon the rhythm of the magical number 3:

Baa, baa black sheep – three baa’s and then wool for the master, the dame and little boy in the lane

Three little bears – with three sizes: big, middle-sized and small

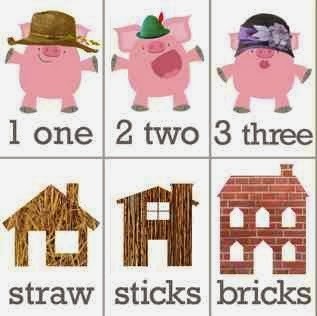

Three little pigs, three billy goats gruff, and so on.

© www.peoniesandpoppyseeds.com

© www.peoniesandpoppyseeds.com From Pat-a-Cake Nursery Rhymes by Annie KublerEven in the tiny story of the nursery rhyme, the rhythm of three sets up the pattern of storytelling, in which the story is set up, there are three examples and then a turning point/conclusion:

From Pat-a-Cake Nursery Rhymes by Annie KublerEven in the tiny story of the nursery rhyme, the rhythm of three sets up the pattern of storytelling, in which the story is set up, there are three examples and then a turning point/conclusion:Set up the story: Pat a cake, Pat a cake, baker's man

Bake me a cake as fast as you can;

Now, build up the story with three elements:Pat it,and prick it and mark it with a ‘B’, Give it an outcome: And put it in the oven for baby and me.

When writing picture books, it is often handy to keep in mind how using the rule of three helps to deliver an exciting, page-turning plot and keep the narrative moving swiftly forward.

1. Sometimes, the whole plot is built upon the rule of three. For example, in Duck in a Truck, when Duck’s truck gets stuck in the muck, Jez Alborough uses three instances to resolve the main problem:

Frog hops down to help. Sheep tries to push. Then Goat, passing by in his motor boat, comes up with the clever plan that solves Duck’s problem:

From Duck in a Truck by Jez Alborough

From Duck in a Truck by Jez Alborough

2. The rule of three is also a great tool for advancing the plot.

Once the author has set-up the story and its central problem, it can help to build-up suspense and work towards a clear turning point in the plot.

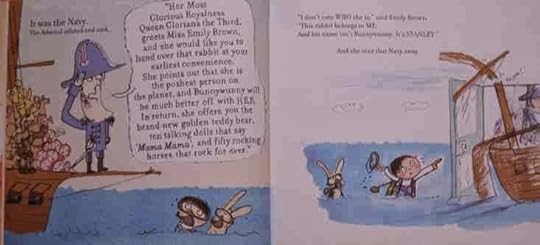

For instance, in That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown, the Queen wants Emily Brown’s much-loved rabbit Stanley in exchange for a golden teddy bear. Feisty Emily Brown tells the Chief Footman firmly that the rabbit is not for sale. So, the Queen sends:

1. The Army

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal Layton

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal Layton2. The Navy

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal Layto

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal Layto3. The Air Force

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal LaytoEach time, they try to exchange ‘Bunnywunny’ for an even greater number of outlandish gifts. And, with each spread, Emily Brown’s consistent refusal builds until she is “FED UP!”

From That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowell and Neal LaytoEach time, they try to exchange ‘Bunnywunny’ for an even greater number of outlandish gifts. And, with each spread, Emily Brown’s consistent refusal builds until she is “FED UP!” Then something must change in the pattern of the plot. So when the Queen has Stanley stolen, Emily Brown has no choice but to confront the Queen herself so she can tell her how to make the golden teddy as loveable as Stanley.

In another example, when Max is crowned King of the Wild Things in Sendak’s classic, three wordless spreads follow, adding drama and indicating the passage of time. These illustrate the wild things’ antics, building up to the turning point when Max orders the them to stop and sends them to bed. Then, realizing he’s lonely, he goes home to his supper and those who love him "best of all".

From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak

From Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice SendakOften, three consecutive examples can also help to advance a sub-section of the plot.

In the classic, Harry the Dirty Dog, when Harry comes home after having played by the railway, played tag with the other dogs and slid down the coal chute (three things!), he is no longer a white dog. His family are sure that this can't be Harry, so he:

“flip-flipped and flop-flipped”“rolled over and played dead” “danced and sang”

From Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion & Margaret Bloy GrahamBut, his family still don't recognize him . . . What follows is a moment of pause, before the story picks up again and Harry remembers to dig up the scrubbing brush he's hidden in the garden and ‘beg’ for a bath!

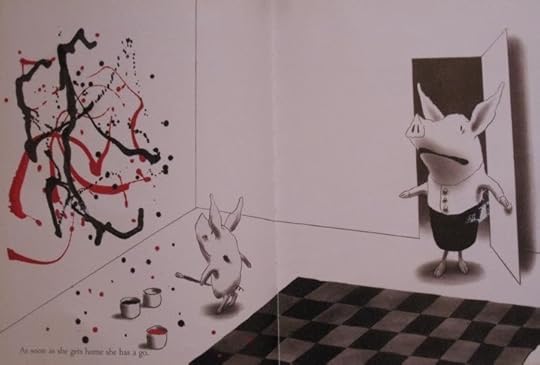

From Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion & Margaret Bloy GrahamBut, his family still don't recognize him . . . What follows is a moment of pause, before the story picks up again and Harry remembers to dig up the scrubbing brush he's hidden in the garden and ‘beg’ for a bath!3. Sometimes, the rule of threes is even used like a mini-plot within the story, as in Olivia:

Olivia admires modern art at the museumShe tries it herself at home . . .

From Olivia by Ian Falconer 3. Then, “Time to think!“

From Olivia by Ian Falconer 3. Then, “Time to think!“ Or as a way to introduce some information about the characters (especially useful as an illustrative device across a page or a spread).

As in Quentin Blake’s Angelica Sprocket’s Pockets: “There’s a pocket for mice,” “and a pocket for cheese” “and a pocket for hankies in case anyone feels that they’re going to sneeze”

From Angelica Sprocket's Pockets by Quentin Blake

From Angelica Sprocket's Pockets by Quentin BlakeIn Olivia, her morning routine includes three elements:

From Olivia by Ian Falconer“In the morning, after she gets up and moves the cat,”“and brushes her teeth and combs her ears,”“and moves the cat”

From Olivia by Ian Falconer“In the morning, after she gets up and moves the cat,”“and brushes her teeth and combs her ears,”“and moves the cat”4. Finally, the rule of three is a really useful way to give the writing a satisfying rhythm.

Here are just two examples:

In Jane Clarke’s Knight School, Little Knight and Little Dragon discover that school is fun:

From Knight School by Jane Clarke & Jane Massey “Little Knight and Little Dragon sang funny songs.“painted fabulous pictures,”“and listened to fantastic stories.”

From Knight School by Jane Clarke & Jane Massey “Little Knight and Little Dragon sang funny songs.“painted fabulous pictures,”“and listened to fantastic stories.”In Mo Willems’ Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs, by virtue of it being a spoof of Goldilocks and the Three Little Bears, practically the whole book follows the rule of three. Here is an example of how Willems uses it at the climax of the story, giving the page a great read-aloud rhythm:

“Just then a loud plane flew by, which sounded pretty much like a trio of Dinosaurs yelling

“NOW” or “CHARGE!” or the Norwegian expression for “CHEWY-BONBON-TIME!"

From Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Mo Willems

From Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Mo WillemsThe rhythm of three is everywhere in picture books! If you look for it, you will start to see how it can work wonderfully to create predictable and unpredictable rhythms in your work, too.

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentor

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. www.blueelephantstoryshaping.com

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. www.blueelephantstoryshaping.com

Published on February 18, 2014 23:30

No comments have been added yet.