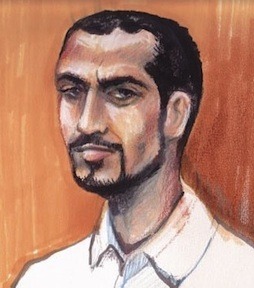

Progress in Canada: Former Guantánamo Prisoner Omar Khadr Moved to Medium-Security Prison

For the first time since his return to Canada from Guantánamo in September 2012, Omar Khadr, the Canadian citizen and former child prisoner of the US, has been downgraded from a high-security risk to a medium-security risk. The move punctures the prevailing rhetoric — from the government, and in the right-wing press — that Khadr is a dangerous individual.

For the first time since his return to Canada from Guantánamo in September 2012, Omar Khadr, the Canadian citizen and former child prisoner of the US, has been downgraded from a high-security risk to a medium-security risk. The move punctures the prevailing rhetoric — from the government, and in the right-wing press — that Khadr is a dangerous individual.

This lamentable rhetoric is the product of three particular factors: racism and/or Islamophobia; a hypocritical refusal to recognize the rights of child prisoners, despite a Supreme Court judgment that was severely critical of the government; and a deliberate refusal to recognise that Khadr’s plea deal at a military commission trial in Guantánamo had nothing to do with justice and guilt, and was agreed to solely to secure his release from Guantánamo, and his return home to Canada, where he was born 27 years ago.

Khadr was just 15 years old when he was seized by US forces, in a severely wounded state, after a firefight in Afghanistan in July 2002. According to the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, which came into force in February 2002, and which both the US and Canada then ratified, juvenile prisoners — those under 18 when their alleged crimes take place — “require special protection.” The Optional Protocol specifically recognizes “the special needs of those children who are particularly vulnerable to recruitment or use in hostilities”, and requires its signatories to promote “the physical and psychosocial rehabilitation and social reintegration of children who are victims of armed conflict.”

Neither the US nor Canada respected Omar’s rights as a juvenile prisoner. The US subjected him to abuse, isolated him or held him alongside adult prisoners, and charged him with war crimes invented by Congress, while the Canadian government sent agents to interrogate him when he was just 16. This led to a ruling in the Canadian Supreme Court in 2010 that the visit and the interrogations had violated his rights — and that also featured in a harrowing documentary film, “You Don’t Like the Truth: 4 Days in Guantánamo,” which was made after the footage of the interrogations at Guantánamo was released as part of a court case.

It was a low point in the presidency of Barack Obama when, in October 2010, Khadr, a former child prisoner, accepted a plea deal in his trial by military commission, in exchange for an eight-year sentence — with just one more year to be served in Guantánamo and seven in Canada — in which he admitted that he was guilty of a variety of alleged war crimes, including killing a US soldier with a grenade, even though it was not his responsibility to plead guilty, even though there were profound doubts about whether actually threw the grenade, and even though the “crimes” to which he confessed had been invented by Congress.

What could be worse for a US president who studied law than to oversee the trial of a former child prisoner in which it became a war crime to engage in military conflict with US soldiers in wartime and in an occupied country?

The answer may be that the behavior of the Canadian government has been worse. After violating Khadr’s rights, the Canadian government dragged its heels regarding his release, so that he only returned to Canada in September 2012 (eleven months later than was agreed in his plea deal), and then imprisoned him in a maximum-security prison, bad-mouthed him as a “convicted terrorist,” and resisted efforts to downgrade him and move him to a medium-security facility where efforts to prepare him for civilian life can begin in earnest.

That only came to an end last September. As I noted in an article in December:

In September, on Khadr’s 27th birthday, I reported how Ivan Zinger, the executive director of the independent Office of the Correctional Investigator, wrote in a letter to Anne Kelly, senior deputy commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada, “The OCI has not found any evidence that Mr. Khadr’s behaviour while incarcerated has been problematic and that he could not be safely managed at a lower security level. I recommend that Mr. Khadr’s security classification be reassessed taking into account all available information and the actual level of risk posed by the offender.” Zinger added that Khadr had “shown no evidence of problematic behaviour while in Canadian custody,” and also stated, “According to a psychological report on file, Khadr interacted well with others and did not present with violent or extremist attitudes.”

Zinger also cited a US military psychiatrist as saying Khadr “showed no signs of aggressive or dangerous behaviour,” and “consistently verbalized his goal to conduct a peaceful, pro-social life as a Canadian citizen,” and noted, “Our office questions the rationale for not using these professional and expert assessments on file.”

In its article about Khadr’s reclassification, the Edmonton Journal noted that, when Khadr was returned to Canada last September, the US authorities described him as a “minimum-security risk based on his behavior in Guantánamo,” and this was also noted by Ivan Zinger.

Nevertheless, in October, in a court in Edmonton, Justice John Rooke, responding to a habeas corpus petition submitted by Khadr in September, issued a ruling ordering him to remain in a maximum security federal prison rather than being moved to a provincial prison, “limiting his chances for parole,” as the Toronto Star described it.

In December, however, Khadr was finally “reclassified as a medium-security risk,” a decision taken by Kelly Hartle, the warden at Edmonton, “reflects a ‘plethora of evidence’ from US authorities and Canada’s prison ombudsman that Khadr never was a maximum-security threat,” as the Edmonton Journal described it.

The Edmonton Journal speculated that Khadr’s move to a medium-security facility would take place early in the New Year, but it has only just happened now. Last Wednesday, one of his lawyers, John Kingman Phillips, explained that he had been moved to Bowden Institution in Alberta province, a medium-security facility, with a minimum-security annex. As AFP put it, accurately, the Canadian government had “resisted the 27-year-old’s transfer from a Canadian federal penitentiary to a more comfortable provincial correctional facility for petty criminals and young offenders, calling it an attempt to lessen his punishment.”

“We are pleased to see Canada finally acknowledge that Omar is not a dangerous individual,” Phillips said in a statement, adding, “We trust that this is the first step by Canada in providing Omar with treatment that is appropriate for someone who is a former child soldier.”

As the Calgary Sun reported, on Friday, after visiting Khadr at Bowden, Phillips said he “was looking very good today.” He also said that the prison move “falls into the ongoing objective of an eventual parole for Khadr,” as the Calgary Sun described it.

“I think the hope is now that there will be more of a recognition that his security level should be dropped down to minimum and he’s hoping to get into some programs and the sort of things that he needs to prepare him to re-enter Canadian society,” he said, adding, “The focus should be on rehabilitation, and that means trying to set it up so he’s got education, he has counselling and that sort of thing and to date he hasn’t had very much of that.”

Phillips also said, “We want him out. We want him to re-integrate into Canadian society.” He added, “If his name wasn’t Khadr, frankly I think we’d be having him go around from campus to campus and place to place talking about what it was like to be a child soldier. Instead we’ve treated him as if he were an adult criminal … and treated him poorly, from Canada’s perspective.”

He also noted that Khadr “is keen on getting his education and bettering himself,” as the Calgary Sun put it. noting, Philips called him “an amazing kid,” and said, “He works very hard and loves to study. He’s a gentle, nice man who for some reason managed to survive some of the worst incarceration conditions in the world and still is a human being.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers