Guest Post by Nora on Characterization

Happy Valentine's Day! I have a really special treat today that I can't wait to share! The library here has a writing group that I participate in and utterly love. The members are amazing and have wonderful stories and great writing that I look forward to talking about twice a month. Nora has been a regular since I first started attending and she has a really introspective and interesting post to share with you all today. I know we'd both love to hear your thoughts so be sure to drop a comment!

I procrastinate by reading Amazon reviews, and I'm always surprised at how five-star reviews of pretty much any popular novel admire the sympathetic, well-drawn characters with psychological depth who grow and change and the one-star reviews of the same book complain about boring, one-dimensional characters who never grow and in addition are raving Mary Sues or eternal bratty adolescents. It seems that 1) characterization makes or breaks readers' experience of a book and 2) the qualities people react to aren't adequately covered by the usual formulas.

So I tried to figure out some of the factors that go into this, from my perspective:

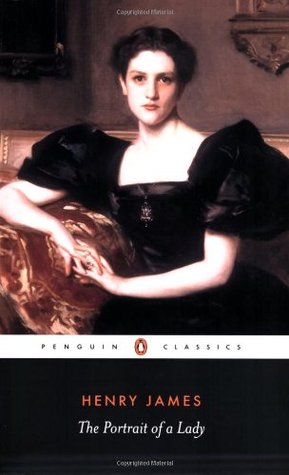

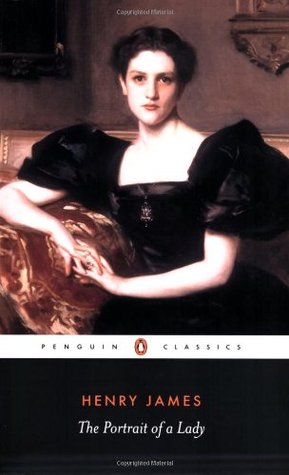

1. Descriptions of characters. In high school English classes, I'd be surprised at how my classmates would completely ignore authors' complex, thoughtful descriptions of *what kind of people the characters were* and judge the characters entirely based on how they acted. Probably because I'm lazy, I actually prefer telling to showing. A well-written character portrait goes much further toward making me feel that a character is a distinctive individual than a set of choices, especially when those choices fall well within the conventions of the genre. I realized at some point on the way to my English degree that that's the reason I liked A Portrait of a Lady by Henry James when it's what I think I hate in a book--pure realism, people ruining their lives over their stupid love lives. The narrator and all of the characters are always describing one another, so instead of having to build impressions of characters from the ground up, I can try to form a more complete picture from a variety of different people's clever ideas. So a character described in great detail might strike me as well-developed and another person as flat.

I realized at some point on the way to my English degree that that's the reason I liked A Portrait of a Lady by Henry James when it's what I think I hate in a book--pure realism, people ruining their lives over their stupid love lives. The narrator and all of the characters are always describing one another, so instead of having to build impressions of characters from the ground up, I can try to form a more complete picture from a variety of different people's clever ideas. So a character described in great detail might strike me as well-developed and another person as flat.

2. The flip side of that -- what the character does and what happens to them, viewed from the outside. Unless the author has a main character do something really unusual, I tend to feel that that character is just being a generic person doing the things main characters are expected to do-- experiencing grief, being courageous in spite of fear, falling in love, etcetera -- unless the author or another character points out the implications of her actions explicitly. That character would strike me as flat, while a different reader would see lots of depth and change.

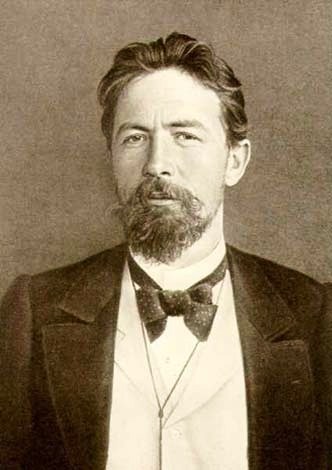

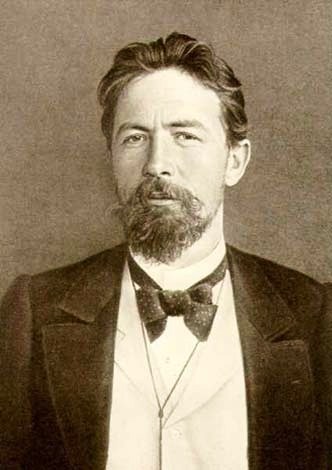

For me, this is Chekhov. I remember one college seminar where I thought "these boring people are falling in love and it's never going to work because it's Chekhov, and also btw the only women he doesn't hold in contempt are sensitive waifs who never do anything coarse like gulp down water or think they're smart" (ok, maybe I'm being a little unfair and off-topic, but…) and when I got to class everyone had these amazing comments that brought out all sorts of subtleties of emotion and relationship dynamics I would never have thought of, because Chekhov is much heavier on showing than telling.

For me, this is Chekhov. I remember one college seminar where I thought "these boring people are falling in love and it's never going to work because it's Chekhov, and also btw the only women he doesn't hold in contempt are sensitive waifs who never do anything coarse like gulp down water or think they're smart" (ok, maybe I'm being a little unfair and off-topic, but…) and when I got to class everyone had these amazing comments that brought out all sorts of subtleties of emotion and relationship dynamics I would never have thought of, because Chekhov is much heavier on showing than telling.

3. Type of language the narrator or character uses to describe characters' feelings and ideas. Different people, different social groups express the same thoughts and feelings in very different ways. What seems deep to one person may be opaque or hackneyed to the next because they're speaking in different cultural codes.

4. Overlap of the reader's emotions and experiences. I think we judge characters on whether we're like them (in decision-making processes, life story, tastes, coping mechanisms, emotions, what have you). Characters too different from us can seem shallow, infuriating, or hard to believe.

5. Detail about psychological states--or more generally, how vividly and in what ways the author evokes the feeling of what it is like to be the character. A character whose author doesn't let you into their body or their head very much may seem shallow or boring to one reader because that reader really wants to get into the character's skin, while other readers might feel distracted from the big picture by too much psychological or emotional detail.

6. Differentiation. Can the author write many different kinds of people or do the characters all deal with the same sets of issues, speak the same language, think the same types of thoughts?

7. Universality versus uniqueness. I tend to find characters well-developed when they are very distinctive and I can look at what they do and say "Yes, that's exactly so-and-so." Whereas some people, I think, find greater depth in more anonymous characters who are defined not by the ways their heads work but by the experiences they have -- experiences that shape them in "universally" human, relatable ways.

Just some thoughts…. I'd be very interested in other people's ideas or examples on this!

I procrastinate by reading Amazon reviews, and I'm always surprised at how five-star reviews of pretty much any popular novel admire the sympathetic, well-drawn characters with psychological depth who grow and change and the one-star reviews of the same book complain about boring, one-dimensional characters who never grow and in addition are raving Mary Sues or eternal bratty adolescents. It seems that 1) characterization makes or breaks readers' experience of a book and 2) the qualities people react to aren't adequately covered by the usual formulas.

So I tried to figure out some of the factors that go into this, from my perspective:

1. Descriptions of characters. In high school English classes, I'd be surprised at how my classmates would completely ignore authors' complex, thoughtful descriptions of *what kind of people the characters were* and judge the characters entirely based on how they acted. Probably because I'm lazy, I actually prefer telling to showing. A well-written character portrait goes much further toward making me feel that a character is a distinctive individual than a set of choices, especially when those choices fall well within the conventions of the genre.

I realized at some point on the way to my English degree that that's the reason I liked A Portrait of a Lady by Henry James when it's what I think I hate in a book--pure realism, people ruining their lives over their stupid love lives. The narrator and all of the characters are always describing one another, so instead of having to build impressions of characters from the ground up, I can try to form a more complete picture from a variety of different people's clever ideas. So a character described in great detail might strike me as well-developed and another person as flat.

I realized at some point on the way to my English degree that that's the reason I liked A Portrait of a Lady by Henry James when it's what I think I hate in a book--pure realism, people ruining their lives over their stupid love lives. The narrator and all of the characters are always describing one another, so instead of having to build impressions of characters from the ground up, I can try to form a more complete picture from a variety of different people's clever ideas. So a character described in great detail might strike me as well-developed and another person as flat.2. The flip side of that -- what the character does and what happens to them, viewed from the outside. Unless the author has a main character do something really unusual, I tend to feel that that character is just being a generic person doing the things main characters are expected to do-- experiencing grief, being courageous in spite of fear, falling in love, etcetera -- unless the author or another character points out the implications of her actions explicitly. That character would strike me as flat, while a different reader would see lots of depth and change.

For me, this is Chekhov. I remember one college seminar where I thought "these boring people are falling in love and it's never going to work because it's Chekhov, and also btw the only women he doesn't hold in contempt are sensitive waifs who never do anything coarse like gulp down water or think they're smart" (ok, maybe I'm being a little unfair and off-topic, but…) and when I got to class everyone had these amazing comments that brought out all sorts of subtleties of emotion and relationship dynamics I would never have thought of, because Chekhov is much heavier on showing than telling.

For me, this is Chekhov. I remember one college seminar where I thought "these boring people are falling in love and it's never going to work because it's Chekhov, and also btw the only women he doesn't hold in contempt are sensitive waifs who never do anything coarse like gulp down water or think they're smart" (ok, maybe I'm being a little unfair and off-topic, but…) and when I got to class everyone had these amazing comments that brought out all sorts of subtleties of emotion and relationship dynamics I would never have thought of, because Chekhov is much heavier on showing than telling.3. Type of language the narrator or character uses to describe characters' feelings and ideas. Different people, different social groups express the same thoughts and feelings in very different ways. What seems deep to one person may be opaque or hackneyed to the next because they're speaking in different cultural codes.

4. Overlap of the reader's emotions and experiences. I think we judge characters on whether we're like them (in decision-making processes, life story, tastes, coping mechanisms, emotions, what have you). Characters too different from us can seem shallow, infuriating, or hard to believe.

5. Detail about psychological states--or more generally, how vividly and in what ways the author evokes the feeling of what it is like to be the character. A character whose author doesn't let you into their body or their head very much may seem shallow or boring to one reader because that reader really wants to get into the character's skin, while other readers might feel distracted from the big picture by too much psychological or emotional detail.

6. Differentiation. Can the author write many different kinds of people or do the characters all deal with the same sets of issues, speak the same language, think the same types of thoughts?

7. Universality versus uniqueness. I tend to find characters well-developed when they are very distinctive and I can look at what they do and say "Yes, that's exactly so-and-so." Whereas some people, I think, find greater depth in more anonymous characters who are defined not by the ways their heads work but by the experiences they have -- experiences that shape them in "universally" human, relatable ways.

Just some thoughts…. I'd be very interested in other people's ideas or examples on this!

Published on February 14, 2014 05:00

No comments have been added yet.