Sharp Soap: Why I’m An Arrow Fangirl

I’ve been on a writing wonk tear recently. I had two books going at once, and both were blocked, so I threw myself into good TV, trying to find a different way into story and ended up with a third book because I’ve become so fascinated by episodic storytelling. I’ve been taking apart everything I’ve been watching, trying to see how it works or doesn’t work, and there are several series I’ve been particularly fascinated by because of the choices their showrunners make, good and bad. I’ve learned a lot from Sherlock, Life on Mars, and Person of Interest among others, but the show that has reawakened my old zest for storytelling is an over-the-top superhero series that I started watching because I was stuck in a rental house and losing my mind. It took me a couple of episodes to notice what the writers were doing on Arrow, but once I wrapped my mind around it, I realized that there was a lot the show could teach me if I was just open to it. If I had to use one word to describe the showrunners and writers behind Arrow, it would be “fearless.” Also, possibly “drunk,” because these people will go anywhere.

When I was doing my MFA, the most obscene words in my vocabulary were “sentimental” and “melodramatic.” Fiction, I learned, should be cool, controlled, understated, sophisticated. All writers walk a line between over-the-top schmaltz and no-pulse distance, but it seemed to me that while romance writers (for example) often fell into melodrama, literary writers (for example) often wrote stories that sat on the page like ice cubes. Trying to walk that line made writing story really difficult until I had an epiphany while writing Bet Me: I realized that I didn’t want to be cool, that if I fell off that line, I definitely wanted to fall into the hot side: I wanted to embrace the soap and chew the scenery, I wanted to give my readers a ride. Then I hit a very long bad patch where a succession of life trucks hit me, and I lost my way and started second-guessing myself. I was spending so much time worrying about what was smart and believable, I didn’t believe anything I wrote. Watching Arrow reminded me of the key part of “I can do anything”: I really can do anything if I start with a clear vision of what I want and where I’m going, a kind of focused insanity based on a strong protagonist with a strong goal and an equally strong antagonist, and then after that, just go for it, no fear, screw the people who raise their eyebrows. Eyebrow raising is easy, focused anything-goes storytelling is not. The people behind Arrow are nuts, but they know where they’re going. The show is a beautiful example of controlled over-the-top storytelling, a pretty much perfect balance of grounded reality and insane fantasy, all of it intelligent, whacked-out fun, and I am now a complete Arrow fan girl, with extra grateful squee for the writers who reminded me of why I decided write fiction in the first place.

So here’s what I’ve learned studying Arrow.

WARNING: The rest of this post is full of spoilers. No, really, MAJOR spoilers. Don’t whine later that I didn’t tell you. MAJOR SPOILERS.

Adapting a comic book character’s story for a general audience isn’t easy, especially if that character has been around for seventy-three years, been retconned several times, and has interacted with a galaxy of other characters, many of whom have superpowers. The sheer weight of the source material can smother storytelling (not to mention the whole “willing suspension of disbelief” thing), but the people behind Arrow have averted that by making some very smart choices.

1. They centered their story on a strong protagonist and then grounded him in reality (or at least possibility).

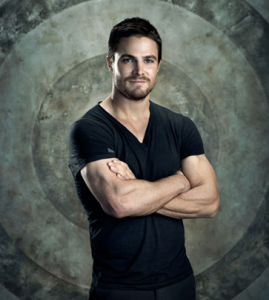

If you’re writing a comic book character, you start over-the-top, but Arrow’s Oliver is a human being, not a superhero; he’s just a rich playboy who does a lot of pull-ups and then goes out and defeats bad guys with a bow and arrow. How is this possible? Oliver gets shipwrecked on an island thanks to his father’s secret career as a maniac, and then gets put through hell by a variety of Really Bad People which turns him into the beta version of the Terminator. I have to admit, the flashbacks to the island leave me cold, but they do explain why Oliver can do so many super-heroic things as a mere human: five years of torture, combat training, and new information coming out of nowhere to blindside him have have taught him to cope quickly with reversal and then put an arrow in it. Anybody coming into Arrow should realize that this is fantasy TV, but because the protagonist is grounded in reality (or at least possibility), the events of the story are grounded, too, which is good because the plots feature things like an earthquake machine and John Barrowman. If you’re bringing the crazy in the rest of the story, make your protagonist the calm, (relatively) stable, believable center that everything else swirls around. Stephen Amell gets a lot of credit here; he’s done amazing things playing a dimwit playboy, a superhero, and a superhero pretending to be a dimwit playboy. (Also, the abs.)

2. They made their protagonist vulnerable by surrounding him with people he cares about.

The big problem with a powerful protagonist is that he’s powerful. That is, Oliver is not an Ordinary Guy hero (that would be Barry Allen); he’s a Prince, immensely wealthy, immensely charming and immensely good-looking. When you start with a Prince instead of the Ordinary Guy, you have to do something to make him vulnerable. (You may have noticed I’m hipped on character vulnerability lately. Hey, it’s crucial, okay?) So another smart thing the Arrow people did was give Oliver family and friends that are important to him. (And again, credit goes to a cast who have really inhabited these characters not only with gusto, but with a complete lack of fear.

For the family, they borrowed heavily from Hamlet in the beginning and then let go of that trope, making the stepfather a great guy and giving Oliver’s mom, Moira, a back story that the Greeks would have called too much drama. Moira has enough nervous energy to power an earthquake machine and enough secrets to keep her nervous for a long time; it’s not every mom who hires thugs to torture her son because she loves him, gets sent to prison because the entire town hates her (well, she did help kill over five hundred of them), gets acquitted through nefarious means, and then decides to run for mayor. The last I saw of her, I think she was planning to off her obstetrician. It takes guts to write somebody like Moira–when she agreed to run for mayor, I laughed out loud–but by god, you can’t take your eyes off the woman.

Then there’s Thea, the bratty little sister, who has arced through a season and a half into a strong, savvy woman who runs both her own nightclub and her boyfriend, Roy, (who used to be an adventurer until he took an arrow in the knee from Oliver; I laughed, but then I’m a horrible person). Roy was just a thug in a hoodie until he had a couple of life-changing experiences and an injection of super-juice, and now he has crazy eyes and is hanging out in the bat cave, suiting up as the Red Arrow (I’m guessing). That means Thea is the daughter of two whack-jobs and the lover of another and at the moment has no idea of either; foreshadowing and expectation: it’s a good thing. This addition of crazy family in peril does two things: It makes Oliver more vulnerable and it adds Soap: seething emotional conflict that is played out in event, not just people emoting, although they do a lot of that, too.

Then the Arrow people left the source material again and gave Oliver a bodyguard named Diggle who learns his secret and becomes his partner with a huge, soapy plot line of his own (dead brother, crush on sister-in-law, still in love with ex-wife, vendetta against a classic comic book bad guy). I really admire writers who say, “So what if he’s a supporting character; let’s give this guy enough story to make his own novel.” (Reminds me of that great writing advice: “Give everybody the best lines.”)

And then, of course, there’s Felicity, the IT girl who wouldn’t know angst if it bit her on the butt the costume department has been showcasing lately. Oliver and Digg get the tortured back story; Felicity gets chipper exasperation and no qualms about saying, “Wait a minute. You’re being dumb.” It’s a team of three equals instead of Oliver and his sidekicks, and that makes them even more important to him, which makes him even more vulnerable. Adding Crazy-Eyes Roy to the team is not going to make him any more secure, either. (Although I’m a little worried about it because the Oliver-Diggle-Felicity trio is the heart of this show. So part of me is saying, “Don’t screw with success” and the other part of me is saying, “And this is how you carefully thought yourself into writer’s block, you dummy. Take the risk.” I talk to myself a lot.)

3. They gave the protagonist a series of antagonists strong enough to shape his course.

So the writers took an iconic character, gave him a soapy family and a strong secret team, and grounded it all in reality or at least possibility. Then, thank god, they deliberately lost their collective grip. If they’d left Arrow in that quasi-reality, it would probably still be a good series, but they’d have been missing that comic book POW that’s pretty much the whole point of adapting super-hero stories. So they did the smartest thing anybody telling this kind of story can do: they put in magnificent antagonists, antagonists who cackle with evil glee, insane sons of bitches with scores to settle and cities to level. When your protagonist puts on a hood at night and goes around the city shooting bad guys with arrows, the bad guys need to be hood-and-arrow worthy. One of my favorites is The Count, mainly because Seth Gabel is the kind of actor who chews the scenery but uses a napkin (he knows what he’s eating but that doesn’t mean he’s going to be a pig about it), but the best of the Bad Guys is John Barrowman’s Malcolm Merlin, the man who sabotaged Oliver’s dad’s boat (which killed Oliver’s dad and started his five-year finishing school on the island), impregnated Oliver’s mother (and wait’ll Oliver’s sister finds out about that), turned Oliver’s best friend against him and then (accidentally) killed him (extra points since the guy was Malcolm’s son), and built the earthquake machine which leveled a good chunk of Oliver’s city along with a good chunk of Oliver’s fortune. Then Malcolm died, except he didn’t, and now he’s back, smiling at Moira with dark irony even as she tips off a secret cult of assassins that he’s in town. Never mind how Moira knows a secret cult of assassins; that bitch has a back story that makes Maleficent look like a 7-11 clerk. Any episode that has Moira meeting Malcolm in a dark parking lot is a good episode: Susanna Thompson and John Barrowman practically quiver with glee as they snarl at each other, great foils to Oliver’s steadfast nobility. Also, a big round of applause for bringing in Amanda Waller to recruit the Bronze Tiger for the Suicide Squad. That can only lead to good things, story wise.

4. They know that great story is fluid and alive, so they abandon anything that isn’t working, they keep the turning points and the reversals coming, and they don’t save anything for later.

One of things that’s most inspiring about this show is how fast and fluid the story planning seems to be. The writers seem to recognize what any smart novelist knows: a series, like a novel, is a marathon, not a sprint, and in the long haul, as you write, stuff happens creatively that you have to pay attention to. If you want to make the story gods laugh, start with an outline. If you want to kill your story, stick with the outline while the story that’s trying to breathe beneath it suffocates. The Arrow writers were playing fast and loose with the canon even before the series started, but the way they’ve paid attention to what’s working in the story and what isn’t is brilliant. Last season’s romance between Diggle and his sister-in-law wasn’t working even though both characters were well-rounded and sympathetic; it was just too complicated with the dead brother in between them. This season, Digg’s not hanging out with the sister-in-law any more; when Oliver asks why, Digg says, “It was too complicated with my dead brother between us.” There’s such smart simplicity to a story that tells the truth and moves on.

Even when they’ve got story lines that are working (which is most of the time) they revise and upend to keep things fresh. Oliver’s immense wealth was making things too easy for him, so Malcolm Merlin destroyed half the city and took Oliver’s net worth with him; Oliver is still a long way from poor, but now he has to put up with a bitchy business partner named Isabel and a city that hates his family. (Really, Moira, you think they’re going to vote for you for mayor?) Oliver finds out Sarah is alive back on the island and barely has time to celebrate before he fails to save Shado. Oliver decides to be a good guy and not kill anybody any more only to be forced to kill to save Felicity. Every time Oliver takes two steps forward, the writers hit him with something that knocks him back a step-and-a-half. That surprise and reversal aren’t just keeping Oliver on his toes, they’re keeping the viewer paying attention, too, and the Girls in my Basement saying, “Do that, do that.”

And finally, the Arrow people understand that story should not be rationed, that keeping the things moving is what makes story great, so they cram as much action and emotion as possible into every week; one episode of Arrow would make six episodes of Agents of SHIELD and an entire season of The Mentalist. Also they are not one-note writers: if you’re not enjoying the episode, wait five minutes and it’ll become a different show altogether (see Esther Inglis-Arkells’s essay, “Arrow Splits Itself Into Four Fantastic (and Nostalgic) Genres.”) Because all the plot lines are linked to the protagonist, they’re integrated, and yet every episode is a plot fruitcake, dense and varied and a solid whole. (And yes, full of nuts.)

5. They integrate their romance subplots into the main plots (mostly).

I’ve done two posts on aspects of the Oliver-Felicity relationship because the fan reaction has been so intense, so it’s probably clear that I’m a Felicity ‘shipper, but I’m an even bigger fan of the way the show integrates its romances into the main plots of the episodes. Oliver has had one-night stands with Laurel and Isabel, whirlwind affairs with Helena and McKenna, and an extremely tense Survivor affair with Shado on the island, and only one of these relationships was separate from the main plot. In fact, one of the reasons Oliver crashes and burns so often is because of the way the romances are part of the main plots: He has to shoot Helena, McKenna gets hurt in the cross-fire and moves to another city to recuperate, Isabel comes on to him only because she’s trying to take over his company and possibly because she’s a villain, and Shado gets executed by an antagonist trying to force Oliver to tell him something. At this point, a character is taking her life in her hands if she agrees to have coffee with him. That may be because Oliver’s entire life is running his company and fighting crime so that’s the only way he meets women, but it also keeps the romances on point and under pressure.

The one place they’re failing, I think, is in not picking a lane for a serious love interest so the show can stop squandering real estate on which-woman-will-it-be scenes. Canon says that the Green Arrow’s great love is the Black Canary, Laurel Lance, but in this show, Laurel has not yet put on the fishnets although her surprisingly-back-from-the-dead sister has. Instead she’s now spiraling into alcoholism and prescription drug abuse while flirting with a politician she rightly suspects is a murderous whack job. (He’s the other candidate running for mayor. Starling City must be in New Jersey.) I’m hoping Laurel meets somebody nice in rehab after Oliver & Co. off the politician because she’s not working as the standard she’s-really-beautiful-and-sexy-and-perfect-so-Ollie-must-love her romantic interest, in part because she’s also the only love interest so far whose story is not integrated into the main plot, so her downward spiral is the story equivalent of your annoying sister who stands in front of the TV so you can’t watch your show.

In the opposite corner we have Felicity, who is not “The Girl” but a full non-romantic player in the story: Felicity has hacked every organization that has an internet presence, gone undercover to cheat at cards in a crooked casino, jumped out of an airplane (and thrown up immediately afterward), and swung through the air on a rope with Oliver three times, which has to be a record for any love interest not named Jane. The writers haven’t used Felicity to tack on a romantic subplot to round out Oliver, they’ve made Felicity and Oliver’s crime-fighting partnership one of the gears that moves the main plots, which is, I think, one of the reasons so many viewers are rooting for her: a love story with Felicity would keep the central stories moving, not distract from them. Add to that the actors playing Oliver and Felicity have remarkable screen chemistry, and that the introduction of Felicity in the third episode saved Oliver from being a boring Grim Bastard all the time, and it’s hard not to start carving “Ollie and Felicity 4 Ever” into your TV cabinet. The first writing wonk thing I did on this show was deconstruct that relationship; if I can set-up a romance on the page the way they’ve done this one, I’ll know I’m back in the game.

6. They know exactly what they’re writing, and they’re embracing that genre with enthusiasm and creativity, making every episode fun to watch.

I think that story enthusiasm is something writers often forget, especially over the long haul. It’s too easy to get trapped in an outline, to concentrate on what happens next without factoring in why the reader will care about what happens next, why the story is just fun/exciting/enthralling to read. We get caught up in parsing out information and forget that unless that information comes wrapped in emotion and action, played out by people we love and hate struggling on the page or screen, unless there are moments that make us sit up and say, “YES!” (or “NO!”), none of that information will matter. Even if the story is tragic, heartbreaking, awful, it has to be fun at a visceral level.

The Arrow writers started with viscera because they started with a comic book super hero, and the temptation to try to be more sophisticated than the source material must have been strong. They have made the stories more sophisticated in execution, but at heart, each episode comes at you like a good comic book page, big visual images that explode across scenes. Oliver shoots arrows that blow things up, that disconnect laser beams, and that disarm bombers, and I can’t be the only person who keeps hoping that he will someday shoot that boxing glove arrow from the comics. Thea gets high and wrecks her car spectacularly, chases down the thug who steals her vintage purse and then kisses him because he’s really cute and tortured and future super-hero material. Digg tracks down his brother’s assassin, breaks into a Russian prison to free his ex-wife, and takes a bullet trying to stop a bomber at a crowded rally. Oliver puts an insane drug pusher in an asylum, then puts him in an asylum again, then puts three arrows in him when the bastard is dumb enough to kidnap Felicity. Moira plots to assassinate Malcolm, then kills her co-conspirator when the assassination goes wrong, then sits in her limousine and weeps over the blood on her hands, Lady Macbeth in a Mercedes Benz. Any one of those things could be a comic book page, all lurid color and hectic movement. That comic book sensibility extends to their enthusiasm for playing fast and loose with convention to get to the juice in their stories. It’s the reason Malcolm isn’t dead (do not give up John Barrowman if you want your scenery chewed), the reason Oliver didn’t save the city last season (a Perfect Hero Who Always Saves the Day is boring and doesn’t change), the reason Sarah came back from the dead to make a terrific Black Canary wrapped in hostility, regret, and fishnet, and Perfect Good Girl Laurel is now Addict Laurel Who Is Pushing Her Luck With An Insane Criminal Mastermind as she drunkenly suggests that Oliver fire Felicity and hire her instead, foreshadowing what I really, really, really, really hope is a slide into villainy, making all of that icy selfishness pay off.

Above all the Arrow writers have embraced the fun, the kind of fun I was having when Oliver yelled at Felicity and I thought, You’re jealous, Oliver, you dimwit, apologize, and then Oliver apologized, and Felicity said, “Does this mean I have a chance . . .” (Felicity, damn it, don’t blow this) “. . . at Employee of the Month?” (Oliver, you jerk, tell her she’s your partner!) and Oliver said, “You’re not an employee, you’re my partner,” and there was some serious eye action and that firm hand on the shoulder, and then they went back to work, and I had to go get a Diet Coke to recover. Fun is all those things that engage reader/viewer emotion, that make us lean forward in our seats, saying, “Oh. My. God,” yelling at the screen because people are doing the wrong thing, because we can’t believe the story is actually going there (Moira’s going to be mayor of Starling City, you know she is), waiting impatiently for what happens next. That kind of fun in story is what makes writing story fun, damn it. How did I forget that?

It’s tempting to describe this show as a guilty pleasure, dumb TV, but that’s wrong. Arrow is smart TV, skilled storytelling, as sophisticated in its structure as it is simple in its emotional hooks. It started strong, and it’s getting stronger because the writers have embraced the crazy while grounding the story in reality, keeping a firm grip on the things that make the story work, especially comic book Good vs Evil, where Good is a conflicted angst-ridden hero with an All-My-Children-From-Hell family and a secret team made up of another equally strong hero and a stealth love interest whose perkiest attribute is her brain, and Evil is John Barrowman.

And that’s why I’m an Arrow fangirl.