Joshua Cody’s memoir [sic]

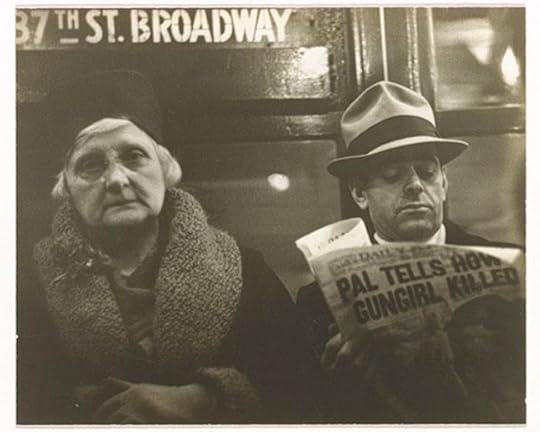

[“Subway Passengers,” 1938, by Walker Evans.]

[“Subway Passengers,” 1938, by Walker Evans.]A memoirist’s risky performance draws praise & provokes rage.

[sic]: A Memoir by Joshua Cody. Norton, 259 pp.

The first two times I opened [sic]: A Memoir, I was impressed by Joshua Cody’s sentences—cool, syntactically complex, allusive. But I didn’t keep reading it because I was working on my own book and sensed immediately that his high-flying persona was at odds with my attempt at a sincere one.

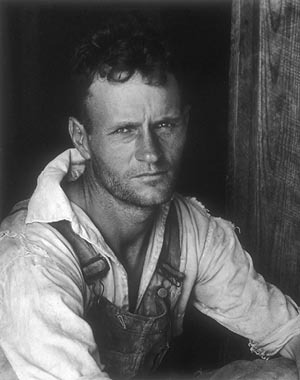

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]Late in 2013 I made it through [sic] and admired it, so refreshingly different from my own writing—or almost anyone’s. I wouldn’t try such a performance and couldn’t sustain one for long if I did. A possible cost of Cody’s approach is that I always felt distanced from him. How much “knowing” and liking a memoirist matters to you is intensely personal, but partly because of this, at times reading [sic] my mind wandered. Cody’s memoir showcases not only the rewards but the risks of a flamboyant (some would say egoistic) persona.

American reviewers generally raved [sic] (see the appreciative review in the New York Times Sunday Book Review), while it got a cooler reception in Europe—the Guardian’s review’s headline: “Joshua Cody’s postmodern memoir of terminal illness is too busy being clever to engage the reader’s feelings.” Guardian reviewer Robert McCrum called Cody “too cool for school” and said, “Part of the essential vanity of this publication is that Cody has been horribly overindulged, and allowed to lard his manuscript with illustrative material. [sic] is a book about sickness that should have been sent to the script doctor. It’s a mess; worse, it’s a pretentious mess. Descended from that great Victorian exhibitionist, ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody, it’s almost as if he’s genetically programmed to perform to the crowd.”

But the pervasive gut-level response of Amazon’s crowd of readers was rage.

It’s hard to pick one thing to show why. Early in the book, there’s a long scene of Cody, in new and dire diagnosis, having sex with a breast-cancer survivor. Before her breasts were removed, she’d had them cast in plaster, and this wall mount above her bed is what Cody gazes upon while they pleasure each other below, as it were, in the ruins.

So Carmilla wasn’t irritated by my admiration. On the contrary, she was flattered. In this way, her breasts still belonged to her. In this way, she was giving them, with so much else, to me. Although my hands had a problem: where should they go? The hollow of her chest. Her dear chest, and my dear hands, meeting there. And I would never tell her this, but I felt as if my hands were gripping the eyestones of a skull. And meanwhile.

But that was why she had her clitoris pierced: such a simple thing, to refocus one’s erogenous zones.

And then, at some point, which would be impossible to determine on the curve of a parabola, or on a map, we were, for the moment, finished: both satiated and done, done with the adolescent anxiety before death—she, seemingly, forever; me temporarily, vicariously, through her.

And she was finished with treatment—she’d refused that well before this point. After the loss of her breasts, enough was enough. People in white jackets had been removing parts of her body for years. And at a certain tipping point she simply said no. She’d just had a scan that clearly showed recurrence.

You’re refusing treatment? I yelled. Cleaning up. She was putting on some music.

“I know I can do it alone. It’s just the mind. More treatment will kill me. I’m treating myself: good food, sex, vodka and cigarettes. And like I was saying before—who cares? If I go this second I’ll be fine. What’s the big deal about death?”

It’s what we’d been talking about before. I’d been worried about death at the restaurant, leaving the restaurant, her hand grabbing mine, entering her apartment. Now I was again.

I don’t want to die, I said.

“Why not?”

After castigating him for wanting to survive to accomplish something, like write a book—“It’s the moment. There are no projects”—she describes the nature of her separate peace that she urges upon him:

“The superb freedom I have—and you will have—is that of a being who’s already died. And it’s so sad, that you died. I can see the sadness in your face. I know that face so well: you’re dead. But in a good way! I mean, it’s sad. But along with this sadness is this great freedom: you can do absolutely anything, there are no consequences, it’s exactly like a lucid dream, except you never wake up.”

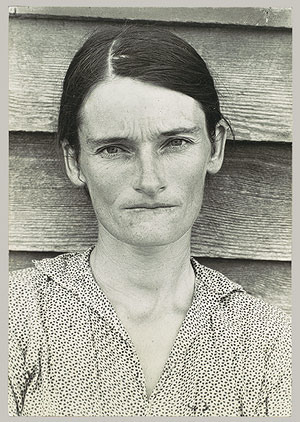

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]As elsewhere, I admire Cody’s courage here in portraying his inner subjectivity, plus his free and fearless use of colons. But I recoiled when his paramour seems callous toward Cody’s newbie-patient fear. He hasn’t died, doesn’t want to, and in fact doesn’t. I didn’t believe her, either: her tough response struck me as a false stance. And the two of them together reminded me of any of Hemingway’s fakey, sentimental couples. Yet here I am in bed with them, or at least with Cody, for 259 pages.

Yet this is tricky. When I reread it I had to admit that hers may be a survivor’s tactic I haven’t myself earned and cannot understand. Her own attitude, she’s entitled to—not what she inflicts on him. This was surely Cody’s effort, to show her living out an active death sentence. She’s on very borrowed time; she’s late-stage, terminal. Yet I still intuited, in the way readers will, that I’d dislike her before she got sick. (And late in the memoir she shows up again and she’s fine.)

You might wonder, as I do, what this critique I’m making of a character in a memoir has to do with its author. I guess it seemed indicative to me. And it does epitomize what irks and excites me about [sic]: its “fine” style, as opposed to “plain,” as explained by Annie Dillard in her great aesthetic analysis Living by Fiction (reviewed). Part of my review:

Fine writing is energetic, though not precise, dazzling, complex and grand, an edifice that celebrates the beauty of language; it strews metaphors and adjectives about, even adverbs, and “traffics in parallel structures and repetitions.” All modernist fine writing begins in Joyce’s collages, Dillard says. “Fine writing does indeed draw attention to a work’s surface, and in that it furthers modernist aims. But at the same time it is pleasing, emotional, engaging . . . It is literary. It is always vulnerable to the charge of sacrificing accuracy, or even integrity, to the more dubious value, beauty. For these reasons it may be, in the name of purity, jettisoned.”

Plain prose, which has carried the day, stands in stark contrast. Again, from my review of Living by Fiction:

Plain writing, like Hemingway’s and Chekhov’s, is a prose “purified by its submission to the world” and represents literature’s “new morality,” says Dillard. This “courteous,” “mature” style emerged with Flaubert, who eschewed verbal dazzle. Clean, sparing in its use of adjectives and adverbs, avoiding relative clauses, fancy punctuation, and metaphor, plain prose can be as taut as lyric poetry. In an extreme form of plain writing (as in Dillard’s own The Maytrees), the simple sentences themselves “become objects which invite inspection and which flaunt their simplicity.” It risks the fatuous: “Hemingway once wrote, and discarded, the sentence ‘Paris is a nice town,’ ” Dillard observes. But plainness helps the writer to honor and to under-write real drama, respecting readers’ intelligence and permitting “scenes to be effective on their narrative virtues, not on the overwrought insistence of their author’s prose.

It’s the prose you’d write for a an audience of terminal patients—one of Dillard’s principles in The Writing Life (reviewed) and in her New York Times essay distilling the book, “Write Till You Drop”:

Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?

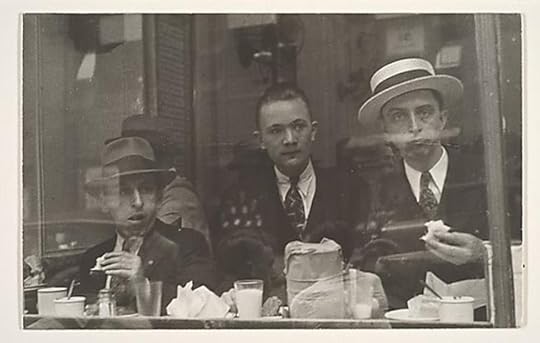

While struggling to make sense of my ambivalence about Cody, I happened across images of the sad but undefeated people in Walker Evans’s photographs. Having been spared yourself, a prosperous and talented person, would you caper about for them in cleverness? For those trashed and transcendent suffering souls?

Cody is a composer, and one can see this in his prose/persona, see the black-clad conductor who, standing with his back to the audience, calls forth with his pointer complex sounds from a full-throated orchestra. He’s right there in the spotlight but you won’t get to know him. At some remove, he’s causing and controlling—coolly orchestrating—the crescendo you’re hearing.

I guess what thrilled me in [sic] was seeing someone flout the plain-prose conventions that I honor. Of course my final take on Cody’s performance comes from my plugging it into my own preexisting temperament, experience, and knowledge. This is the delight and danger of experiencing anyone else’s response to art: Ah, here we have a specimen of “fine” prose . . . You know, people can educate themselves into stupidity.

So one best always check his response, as well, with his gut.

Next: an interview with Thomas Larson about his new memoir of illness.

[“Lunchroom Window, New York,” 1929, by Walker Evans.]

[“Lunchroom Window, New York,” 1929, by Walker Evans.]