Sherlock Sunday 1: “A Study in Pink” by Steven Moffat (Beginnings)

Since we’re starting with “A Study in Pink,” the first episode of the Sherlock series, let’s talk about beginnings.

The beginning of your story is a promise you make to the reader. That means everything in that first scene, especially everything on the first page, sets up all of the rest of the story. I had a creative writing professor who said that the first line eliminates 90% of the possibilities in your story. I don’t know about percentages, but I know that readers (and viewers) are inveterate world builders, story collaborators, who will seize on the first clues they encounter, deduce where the story is going, and set those deductions in stone, treating any diversions from those assumptions as betrayals. That means establishing who the protagonist is, why the reader/viewer should sympathize with him, where he’s standing and when he’s standing there (setting), and how the story is going to present itself (mood) has to happen in the beginning or your reader will take your story away from you or, much worse, reject it entirely. If you’re writing for film, you have a little more time to hold your audience; people tend to settle in when they’re in front of a screen, and they’ll keep watching long after they’d have thrown a book against the wall. But the basic idea is the same: You’re welcoming your reader/viewer into a particular and specific world, asking her to identify with your protagonist (vulnerability is a big help here), hoping to engage her in the trouble/conflict that protagonist is struggling with. Forget about writing hooks; that’s a cheap trick. Hit the ground running by writing story from the first line, and if you start in the right place, your story will be so interesting that the first line will be a hook anyway.

Which brings us to “A Study in Pink.” Sherlock co-creators Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss had to clear a big hurdle from the beginning: They were working with the most famous and possibly most beloved character in fiction, a character that has been interpreted and reinterpreted dozens of times. That meant that before they filmed the first line of their series, people already had some expectations set in stone: Sherlock Holmes would be a great detective, a genius in the art and science of deduction. He would partner with a doctor named Watson. He would live at 221 Baker Street with his landlady, Mrs. Hudson. And he would be at odds with/work with a detective named Lestrade. Then they upped those set-in-stone expectations with the title of the first episode. Calling the pilot “A Study in Pink” meant that every Holmes fan knew they were paying homage to the first story of the original Sherlock, “A Study in Scarlet,” which meant there had better be a dead body in an empty house with the word “Rache” scratched somewhere in blood. On the other hand, Moffat and Gatiss had also given themselves a big advantage in their choice of homage: everybody loves Sherlock Holmes. All they really had to do was Not Screw It Up. That they are succeeding so brilliantly is due in no small part to their great beginning.

Moffat opens the episode with a series of vignettes. First, there’s a hazy nightmare of guns firing, men at war, while a man (Martin Freeman, the world’s favorite Everyman) tosses and turns in his bed. Then he’s sitting on a bed in a sterile, yellowed room, staring into space. Then he’s walking to his desk with the use of a cane; he opens the drawer and there’s a glimpse of a gun as he pulls out a laptop and turns it on, loading a page identified as John Watson’s blog. And then he’s in his therapist’s office, hearing her say he has trust issues, that it’s important that he write down the things that are happening to him, which prompts the last line of the Watson vignettes: “Nothing ever happens to me.” That’s the first three and a half minutes of the ninety-minute story.

Those vignettes establish John Watson as our stake in the story; not just our main point of view in the story, but our emotional connection. You can argue that he’s an observer narrator, that Sherlock Holmes must be the protagonist, but I think this is The Great Gatsby approach to story protagonist: the protagonist really is Watson because he’s the one who changes the most. Nick Carroway may spend his novel talking about Gatsby, but Gatsby never changes; his main service to the story is serving as the impetus for Nick’s evolution into a wiser man. In the same way, John’s going to change into a happier if more exasperated man by the end of this story because of his association with Sherlock Holmes, a man who doesn’t change at all (at least not in this episode). I would argue that another thirty seconds of John staring hopelessly into space would have been a deal-breaker, and that the understated conflict with his therapist is probably the only thing that saves it at the two minute mark, but the choice of opening with John is a good one because it establishes his trouble, which means it establishes his vulnerability, which means it establishes our vulnerability in the story. We’re not going to worry about Sherlock, but John is like us, our placeholder, and he’s in a bad place, and we sympathize. Another good reason to start with John instead of Sherlock: That’s what Arthur Conan Doyle did in “A Study in Scarlet.”

Then there are the credits, which any filmgoer sits through, so they’re pretty much not an aspect of beginning a story. However, Moffat follows up the credits with another series of vignettes, this time of three suicides. They’re beautifully acted and beautifully filmed, and there are three of them so they fit the classic storytelling rule of three-that-make-a-whole, but now we’re seven and a half minutes into the story and all we’ve had are vignettes. Something better happen pretty soon, and by “something,” most viewers would mean “Sherlock Holmes.”

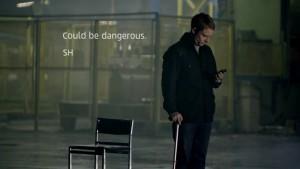

Moffat does something clever here: he gives the viewer Sherlock Holmes without putting him on stage yet. At a press conference, Inspector Lestrade is being hammered by reporters who want him to say that there’s a serial killer in London while he maintains all the deaths were suicides. What could be just info dump–Lestrade explaining the circumstances of the deaths and the police response–is turned into a conflict scene when his explanations are interrupted three times (never underestimate the power of three in storytelling) with one-word texts to every cellphone in the room: “Wrong.” Moffat does his viewers the courtesy of assuming they’re smart enough to know that’s Sherlock, and then ends with a private text to the harried Lestrade: “You know where to find me. SH.”

Then it’s back to John since we’ve been away from him for over six minutes, a lifetime on film. Now he’s sitting again, this time talking to an old friend from med school days. I’m assuming this scene is there for two reasons: it’s the bridge to get Watson and Sherlock together, and it’s a callback to “A Study in Scarlet,” the first direct parallel so far. His friend invites him back to the med school to meet somebody, and everybody knows that’s going to be Sherlock. Expectation established.

But there’s another delay: Sherlock is in the morgue, talking to Molly, the pathologist, a recurring character who has a crush on him. It’s a short scene that establishes Sherlock’s appalling coldness, not only in his treatment of Molly but also in his treatment of a corpse, and it works because we don’t have to attach to him; we have John already established for that. Another benefit to this short scene: this is the guy our vulnerable placeholder is going to spend the rest of the movie with. What’s going to happen when our wounded warrior meets the genius jerk?

And then FINALLY, Watson meets Holmes, in a direct parallel to a scene in “A Study in Scarlet,” updated but not violated, ending with Holmes’ last words to Watson, an invitation to meet him the following evening at the legendary 222B Baker Street. The promise has been made, the important information has been given, expectations founded in the original Doyle stories have been recast into Moffat-Gatiss expectations, and the game is afoot. Or as the New Sherlock says, “The game is on.”

So in the first fourteen minutes of the ninety minute story, Moffat has

• Introduced John Watson as a vulnerable character

• Shown a serial-deaths montage to establish a killer on the loose

Titles

• Introduced Lestrade and given more information about the deaths in the press conference and foreshadowed Sherlock’s entrance

• Shown John resisting change/optimism in the encounter with an old friend

• Introduced Sherlock Holmes being a jerk to Molly

• Shown Sherlock meeting John, beginning John’s character arc from its starting point of “Nothing ever happens to me.”

Which means that in those fourteen minutes, Moffat has established:

Protagonist/POV character and his trouble/vulnerability

Conflict (somebody’s murdering people)

Subplot (Sherlock vs Lestrade/police/ordinary minds)

Subplot (Sherlock vs Molly; unrequited crush)

Main plot (Watson vs Sherlock: “Nothing ever happens to me.”)

Yeah, I know, it still seems as though Sherlock must be the protagonist. He’s Sherlock Holmes. And if you look at the series as a whole, as the episodes as chapters in a novel, I might go along with that, even with Watson introduced first. But looking at just the story of “A Study in Pink,” if Sherlock is the protagonist, then Watson’s “Nothing ever happens to me” will be overwhelmed by Sherlock vs The Killer; we’ll forget John’s vulnerability and become more interested in how Sherlock puzzles out the crime. But if Watson is the protagonist, then we’ll care more about what’s happening to him than to whether the killer is caught. The best way to judge if the promise of the beginning has been kept: What happens at the climax? Who defeats the killer and ends the conflict? if it’s Sherlock, the opening is a lie. If it’s Watson, the opening is a promise kept, a demonstration that his life where nothing ever happened has irrevocably changed and made him a new man. This crucial link between beginning and ending is the reason that you really can’t know where to start your story until you know where it finishes: the beginning is just the set-up, the invitation to the ending.

Now, it’s your turn. I’ve focused on beginnings, but you can talk about anything you want. Not that you need permission; you would anyway, especially with a great story like Steven Moffat’s “A Study in Pink.”

newest »

newest »

I like how you explain the beginning of what the beginning of a story should be. "Everything on the first page sets up the rest of the story." Ah Ha, :)

I like how you explain the beginning of what the beginning of a story should be. "Everything on the first page sets up the rest of the story." Ah Ha, :)