Why Do Sequels Suck? Comparing and Contrasting the Good, the Bad and the Barftastic

Picture this. A great movie is released to critical acclaim. It dominates the box office and leaves audiences clamoring for more. Giddy with their own success, creators comply, announcing that the next chapter is on its way. A sequel: more of what you loved– bigger, better, faster and stronger.

But somewhere along the way, something goes horribly, horribly wrong.

The road to hell seems to be paved with sequels– books, films, etc. that have fallen short of the originals, or just fallen entirely off the map. The worst ones not only leave a sour taste in your mouth, but can actually diminish their predecessors just by association.

The obvious motivator behind sequels is money, but even if we assume every sequel ever made was concocted for purely mercenary reasons, it still can’t explain why so many are so God-awful. And it doesn’t explain why there are some good sequels out there– rare as they may be.

So what is it that successful sequels do, where the bad ones miss the mark? As an author (and currently working on my first sequel) I felt supremely vulnerable to falling victim to the sequel trap. By comparing some of the most successful sequels in film history, and borrowing from a few other resources (including one great article here), some surprisingly consistent trends began to emerge. Not only did I start to see what made a sequel good, but I began to understand where the bad ones went wrong. To keep things orderly, I limited my materials to seven “Successful Sequels” (successful implying critical acclaim, and/or fan favorites) as well as seven “Failed Sequels” (failed implying general disdain, and/or just abysmal). And so, without further ado, it’s time to finally figure out what makes or breaks a Part II. Take note, Hollywood.

1. Characters

Success is bad.

Okay, let me clarify this… What I mean is that successful, well-balanced characters are boring. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with characters getting what they want, fulfilled, happy people tend to come off not only as one-dimensional and forgettable, but downright annoying. That seems to be the reason that in 5/7 Successful Sequels, characters are more troubled. One of the best examples of this can be found in an unlikely place: Toy Story 2 (1999).

Considered by many critics to be one of the most successful sequels ever made, Toy Story 2 seems to do just about everything right. But where this movie really shines is in its character development. That’s pretty impressive, given that the characters are, well, toys. Without human lives, how much character development can we really get out of them? As it turns out, a lot. With the toys’ owner, Andy, growing up, there’s an overall feeling of fearful uncertainty for the future. Woody struggles with issues of identity, and all the toys must confront the reality of death (meaning, for them, abandonment, being sold at garage sales, or put into storage).

Toy Story 2 is also a prime example of another factor of successful sequels: adding new co-stars. It seamlessly brings Jessie the Cowgirl and Bullseye the Horse into the fold. Only 1/7 Failed Sequels added new co-stars to the lineup, while 5/7 Successful Sequels did.

2. Villains

Moving on, we come to a category that is near and dear to my heart. I just love to hate a good villain.

But for some reason, many bad guys just lose their luster in sequels. The temptation to resurrect the dead is just too overwhelming for some writers (think Agent Smith in The Matrix movies). Others just can’t pass up the redemption story– trying to turn the first movie’s villain into a good guy the second time around; maybe even a hero.

In truth, both of these avenues, no matter how appealing they may seem, are the sequel equivalent of shooting yourself in the foot. The dead should stay dead. So instead of resurrecting that old nemesis, one of the most important things to do in a sequel– and utilized in all 7/7 Successful Sequels– is to add a new villain. Perhaps none does this better than the sequel to Batman Begins (2005), 2008′s follow-up, The Dark Knight.

It was probably very tempting to bring back Liam Neeson for a reprisal of his villainous role from Batman Begins (especially considering that his character, Ra’s al Ghul, was immortal in the Batman comics). Instead, Nolan and co. brought in the Clown Prince of Crime, a villain devoted not to money or world domination, but pure chaos. The Joker was so completely unlike what audiences had seen in the previous film, committing heinous crimes with such childlike glee, that it was hard not to like him. But even though he was likable, there was nothing sympathetic about him– which leads me to my next point: bad guys are bad.

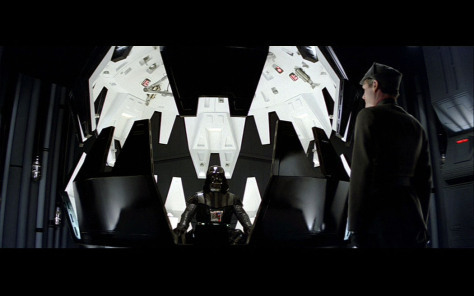

Putting aside the fact that Darth Vader eventually did come back from the Dark Side in a fabulously well-executed redemption plot, there’s nothing redeeming or remotely sympathetic about him in The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Vader is pure evil in this one. In Star Wars (1977) he was an enforcer, carrying out orders, doing what he was told. In Empire, he’s now the one calling the shots. He leads an invasion against the Rebel heroes in hopes of wiping them out completely. He’s constantly reappointing officers because he keeps choking his own men to death. He freezes Han Solo in a block of carbonite– but not before torturing him, first. He cuts off the hand of his own son, and then tries to convince Luke to join him in conspiring against his only ally, the Emperor. He is evil and villainous to the core, and it works. Another great example: the Russian in Rocky IV (1985).

3. Story

Enticing as it might be for writers to revisit their past successes, the scary truth is this: just because it worked the first time doesn’t mean anybody wants to see it again. The worst thing a sequel can do is retell the same old story. I’m talking to you, every horror sequel ever made.

It’s not enough to just reunite the old cast for another romp. And with all this talk of villains being villainous and characters becoming more troubled, it shouldn’t be surprising to learn that when it comes to sequels, you should always go darker. 5/7 Successful Sequels went darker, while only 2/7 Failed Sequels managed to follow this advice. And for a lesson in darkness, look no further than Dr. Indiana Jones.

To be fair, the original movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), was far from a “romp”. I mean, a guy’s head exploded. Still, Raiders looked tame compared to its 1984 sequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. With scenes of still-beating hearts ripped from human sacrifices, people being burned alive, nightmarish, drug-induced brainwashing, and child slaves getting whipped by devotees of a death-worshipping cult, the stark contrast in subject matter between Raiders and Temple makes this sequel unexpectedly fresh. Going darker is a great way to add peril and legitimacy to a story.

4. Continuity/References

Remember all those funny one-liners from Pirates of the Caribbean (2003)? Well if you don’t, you definitely will by the end of the sequel, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), which repeats just about every pun, witty remark and memorable moment from the original.

It feels petty to even mention this one; I mean, I’d feel like I was just nitpicking if the data didn’t support it, but the numbers don’t lie. 6/7 Failed Sequels featured an overabundance of references to the first film. For another example of this, see The Hangover Part II (2011). Some even take it a step further, by jumping through hoops, trying to invent importance out of earlier events instead of moving the story forward.

Overabundance of references and continuity overload both tie in with another important sequel characteristic: making the story able to stand alone.

I’d probably already seen Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) five times before I’d ever seen the original. The great thing about this film? You don’t need to see the original to enjoy the second one. Terminator 2, like so many other great sequels, does not depend on its successor. Its plot does not– like so many bad sequels– hinge entirely on the original. You could walk into this movie without ever having seen the first one, and have almost exactly the same experience, making it not only accessible to a wider audience, but less strenuous on the brain. The same is true of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (which adheres to an almost 007-like isolation), as well as Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn, and The Dark Knight. Try it with either of the Pirates of the Caribbean sequels– or worse, The Matrix sequels– and by the end, your head will hurt almost as much as your stomach.

5. Genre/Scenery

This category might not be as obvious as some of the others, but changes to genre and scenery actually play a fairly significant role in the success or failure of a sequel. A lot of sequels add a change of scenery as a means of switching things up, some successfully– like Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992) or Predator 2 (1990). Others, not so much– like Taken 2 (2012), which takes place on the opposite side of Europe, and yet somehow still looks like they’re on the same soundstage as the original.

But going beyond scenery, sequels also tend to experiment with genre more than one might realize. 6/7 Successful Sequels added a new genre from the original, and 6/7 Failed Sequels did not add a new genre. Still, it’s not fool-proof. Playing with genre can be a dangerous game. Enter, Spider-Man 3 (2007).

An awful lot went wrong with Spider-Man 3, but for the sake of time and space, we’ll focus on one, simple fact: there were just too many plot-lines, all getting tangled into a great big, sticky… web?! Walked right into that one.

In addition to the tried-and-true Action/Adventure Genre, Spider-Man (2002) struck an excellent balance between telling both a Maturation Plot (aka Coming-of-Age Story) through Peter Parker/Spider-Man, as well as a Punitive Plot (Punishment) through the tragic downfall of his enemy Norman Osborn/Green Goblin. Spider-Man 2 (2004) essentially did the same thing, just with a different villain. But by the time Spider-Man 3 rolls around, there are too many genres and character arcs for one film to handle. In addition to straight Action/Adventure, Peter Parker has been exposed to the black, “evil” suit and is going through a Testing Plot. His friend, Harry Osborn, is falling through a Punitive Plot identical to his father’s. The villain Sandman is simultaneously going through a Redemption Plot. I’m pretty sure there was also a love story crammed in there, and the final story arc involving Eddie Brock as Venom was so brief it’s hardly even worth mentioning. All these plot lines no doubt looked epic and thrilling on paper, but instead, led to an unfortunate lack of focus. (I tried to keep that one short, and it still almost turned into a rant…)

Summary

So what have we learned?

Make Characters More Troubled - characters make story, and internal struggles always add dimension and gravity

Add New Co-Stars - a new supporting cast can influence character development across the board

Add a New Villain - preferably one who could wipe the floor with the old villain

Keep Bad Guys Bad - and dead, if applicable

Go Darker - and show the audience that nothing will ever be the same

Make it Stand Alone - move the story forward, and leave the past where it belongs

Experiment With Genre - but be careful…!

The majority of Successful Sequels utilized all of these techniques, while the majority of Failed Sequels ignored them. You can’t argue with the facts.

Conclusion: Sequels Don’t Have to Suck

We can see by the evidence that tangible elements of setting, story structure and character development are consistent hallmarks of a successful Part II.

Sequels are a double-edged sword, but they don’t have to suck. When a story is so good that it leaves fans yearning for more, it’s only natural that creators answer the call. All we can really do is cross our fingers, and hope it’ll be a precious gem and not a barftastic failure.

For your viewing pleasure/displeasure, check out the fourteen films examined for this post, and see for yourself what makes or breaks a sequel.

Successful Sequels:

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

The Dark Knight (2008)

Toy Story 2 (1999)

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984)

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn (1982)

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006)

Rocky IV (1985)

Failed Sequels:

The Hangover Part II (2011)

Spider-Man 3 (2007)

Taken 2 (2012)

Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007)

The Matrix Revolutions (2003)

The Sandlot 2 (2005)

Jurassic Park 3 (2001)

Take Our Poll