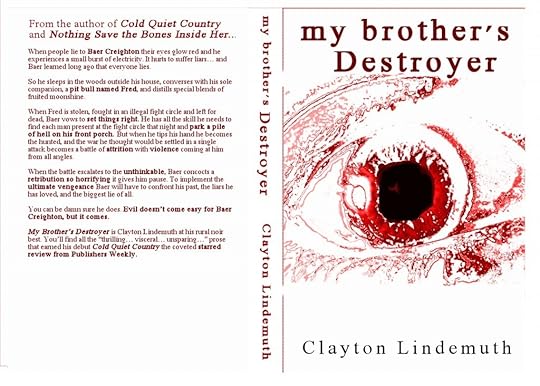

Another tentative book release… Does this cover grab you?

I’ve had a handful of novels written that never seemed to be the right time to release. I’ve secured enough feedback to be 99% likely to release Nothing Save the Bones Inside Her next month. (Thanks to the many folks who volunteered to read it and respond with insights. And for the generosity of praise. There are still a couple of folks reading it who I regard with great respect, and a sour view from either of them would likely make me hesitate. Otherwise, I’ll be releasing Nothing Save the Bones Inside Her next month.)

Next: my brother’s Destroyer. This is my fifth novel. The above was my second, and Cold Quiet Country my third. The sixth, by the way, is a prequel to Nothing Save the Bones Inside Her. The seventh… well, that’s a secret. The first and third are undergoing revision.

Anyway, this cover is for: my brother’s Destroyer. There is a possibility that I will choose the traditional publishing route for this one… but in the meantime I’m preparing as if I’ll release it at the same time as Nothing Save the Bones Inside Her. Like last time, I’m looking forward to your thoughts on the cover… does it grab you? Does it make you likely to read the back? And does the back make you likely to read the first page?

I’ll put the first couple pages below, just in case the front and back make you want to see what the voice is like. Please email me at claylindemuth at gmail dot com, tweet to me at @claylindemuth, or just leave a comment below. Many thanks.

ONE

I see the bastards ahead, fractured by dark and trees. Twenty—more. They voices led me this far. I touch the Smith and Wesson on my hip. They’s a nip in the air, harvest near over. Longer I’m still, colder I get.

One of these shitheads stole Fred.

Problems for him.

I’m crouched behind an elm, pressed agin smooth bark.

It’s dark enough I could stand up and wiggle my pecker at them and they wouldn’t see. They’s occupied around a pit. Place swims in orange kerosene light with so many moths the glow flickers. Hoots and hollers, catcalls like they’s looking at naked women. Can’t see in the circle from here, but two sorry brutes inside are gutting and gouging each other. Two dogs bred for it, or stole from some kid maybe, or some shit like me.

All my life I got out the way so the liars and cheaters could go on lying and cheating one another. I can spot a liar like nobody. But these men is well past deceit.

One of these devils got hell to pay.

Fifty yards, me to them. I stand, touch Smith one more time. Step from the tree. A twig snaps. I freeze. Crunch on dry leaves to the next tree, and the next. Ten yards. If someone takes a gander he’ll see me—but these boys got they minds on blood sport.

Sport.

I test old muscles and old bones on a maple. Standing in a hip-high crotch, I reach the lowest limb and shinny. Want some elevation. See men’s faces, other side of the ring—and if I don’t see dogs killing each other, that’ll be fine.

I know some of these men—George from the lumber yard, and the Mexican runs his forklift. They’s Big Ted; his restaurant connects him to other big men from Chicago and New York. Ted’s always ready to do a favor, and tell you he done it, and send a monthly statement so you know your debt. Kind of on the outskirts, Mick Fleming. And beside him is Jenkins. Didn’t expect to see the pastor here.

“Lookit that bastard! Kill ’im, Achilles! Kill ’im!”

Why looky looky.

That’s Cory Smylie, the police chief’s son, shouting loudest. Cory—piece a shit stuffed in a rusted can, buried in a septic field under a black cherry tree, where birds perch and shit berry juice all day.

I make the profile of Lucky Jim Graves, a card player with nothing but red in his ledger.

The branch is bouncy now, saggy. Stiff breeze and I’ll be picking myself off the ground.

I think that’s Lou Buzzard. The branch rides up my ass like a two-inch saddle and each time I move, leaves rustle. But I want to know if that’s Lou ’cause he’s a ten-year customer. Be real helpful if these devils was already drinking my likker. Little farther out and I’ll see.

Snapped limb pops like a rifle. I’m on the ground and the noise of the fight wanes, save the dogs. Hands move at holsters and silver tubes sparkle like moonlight on a brook. These men come prepared to defend the sport, and got more dexterity than I could muster on two sobers.

“You there!”

Voice belongs to a fella I know by reputation, Joe Stipe. We’ve howdied but we ain’t shook. A man with a finger on every sort of business you can imagine, including mine. Got a truck company, the dog fights, making book, and a few year ago sent thugs to muscle me out of my stilling operation. We ain’t exactly friendly.

Men gather at Stipe’s flanks as he tromps my way. “Grab a lantern there, George. We got company.”

I sit like a crab. The light gets in my face.

“Why, that’s Baer Creighton,” a man says.

“Baer Creighton, huh? Lemme see.” Stipe thrusts the lantern closer.

“That’s right.”

“Don’t tell Larry,” another says.

“He ain’t here tonight,” Stipe says. “What the hell you doing, Baer? Mighta got your dumb ass shot.”

“I was hanging in the tree because you’s a bunch a no-count assholes and I’d rather talk to a bag of shit.”

They’s quiet, waiting for something let ’em understand which way things’ll break.

Not tonight, boys. But I’ll goddamn let you know.

The hair on my arms floats up and static buzzes through me. I look for the man with a red hue to his eyes. Ain’t hard to see at night—it’s always easier at night—and it’s the one said, “Don’t tell Larry.”

I don’t try to see the red, or feel the electric. Gift or curse, I subdue it with the likker. Got it damn near stamped out.

“It’s just Baer,” Stipe says.

The men disperse back the fight circle, where a pair of dogs still tries to kill each other. Stipe lingers, and when it’s just him and me, he braces hands on knees so his face is two feet from mine. I smell the likker on him.

My likker.

“Come watch the fight with us assholes.” Stipe looks straight in my eyes. “And later…you breathe a word of this place, I’ll burn you down.”

“Didn’t come so I could write a story in the paper.” I crawl back a couple steps and work to my feet. My back and hips feel like a grease monkey worked ’em with a tire tool, but I won’t show it. We’s face to face and Stipe’s a big somebody; got me by a rain barrel. The fella give me the electric stares from the fight circle, that circle of piss and blood and shit and clay.

Expected to see Larry here. After thirty years of meditation, I don’t know whether to blame myself for stealing Ruth or him for stealing her back.

“I believe what you said about the newspaper, Baer,” Stipe says. “So what brought you to my woods?”

I meet his eye for a second or two, and take note of his bony brow. “Nothing to say on that.” I turn and after a step he drops his hand on my shoulder. Spins me. I get the juice like I stuck my tongue on a nine-volt. His eyes pertineer shoot fireworks. He’s so fulla deceit and trickery, he’s liable to shoot me straight.

I lurch free.

“You remember what I said. I’m going to burn you down. I’ll find every sore spot you got and smack it with a twenty-pound sledge. You’ll pull your head from a hole in the ground, Baer, just to see that awful sledge coming down one last time. You best get savvy real quick. Don’t mess with a man’s livelihood.”

Heard rumors on Stipe going way back—how his truck company made lots of money after his competition died under a broke hydraulic lift with a sheared pin. Curious, is all. Got them lugnuts by his side when you see him in town, like he’s some president got a private secret service. Always some jailhound on the work release with a mug like a fight dog after a three-hour bruiser.

“They’s no such thing as impunity, Stipe.”

His look says he don’t ken my meaning and that’s fine as water. You’ll smack me down and every time I look up, I’ll see Fred. I’ll shove that impunity down your throat and you won’t know you’re filling up on poison. That’s what I’m thinking, but words ain’t worth a bucket a piss. I back away. His eyes is plain-spoke menace.

I’m so torqued I got to look for my voice. “Ain’t quite time to call it war. But I’ll let you know.”

I tramp into the woods and every square inch of my back crawls. I get far enough the static don’t bother me; bullets do, and if I was twenty years younger I’d run in spite of low-hanging limbs. But I’m fifty and my hipbone feels like it was dipped in dirt, so I stomp along and eventually I’m deep enough into the woods I turn.

Stipe still looks my way, but him and his boys is all shadows, demons.

Farther out, when the fight circle’s a slight glow through distant trees, I rest a minute on a log. They know I live and work at home. Wasn’t thinking I’d tip my hand just yet, but part of the curse of seeing lies is not being worth a shit at telling them. And knowing the bastard who stole Fred was in that crowd works agin my better judgment. It’s hard to hold your tongue while the plan sorts out—you want to let the bastard know something god-awful brutal is coming his way.

I stand, work my joints loose. I come to Mill Crick and follow south a mile, and pause at my homestead, a tarp strung tree to ground, a row of fifty-five gallon drums, a boiler and copper tube.

Fred growls.

“It’s me, you fucking brute.”

Fred’s in shadows under the tarp. His tail taps the diesel turbine shipping crate he sleeps in. I hammered over the nails and reinforced the corners with small blocks, and it’s been home to four generations. If I was to pick the hairs between the boards, they’d be white like Fred, red like George, brown like Loretta, and brindle like Phil. All relations of his, though I couldn’t name the begats.

His voice turns quiet.

He’s got words and I got words and we know each other well enough to talk without losing hardly anything to translation. He knew it was me tramping into camp when I was a half mile out, most likely. He only growled to show disapproval, and now it’s done, he can go back to sleep.

Poor son of a bitch needs it.

Fred’s one of them pit bulls they like to fight so much.