Points and Turns

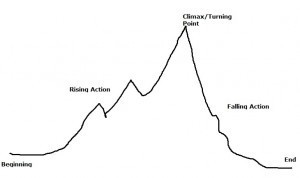

When I was in school, back in the Jurassic, I was taught the basic plot structure and its variations: beginning, rising action, climax or turning point, falling action. The chart that went along with it looked something like this:

For years and years, I thought this was the only plot structure there was; the only things that changed were how many peaks and valleys you had in the “rising action” part and where in the story the turning point came (it could, my teachers told me, happen as early as halfway through or as late as 90% through).

The climax, also called the turning point, got the lion’s share of attention in my classes. It was supposed to be the point of greatest tension in the story, the point after which, however much story there was to come, the end was inevitable. (This always made me wonder why the “turning point” in a Sherlock Holmes story wasn’t always the moment in the first few pages where Holmes says, “Yes, I’ll take the case.” Because from then on, the ending was inevitable…)

Somewhere in the past thirty or forty years, things have gotten a lot more complex. For one thing, at least half the things I read talk about “turning points” – plural. People seem to mean one of two things by this: either they are talking about the smaller peak-points on the “rising action” side of the graph, where something tense and dramatic happens that changes the direction of the story, or else they are talking about the specific spots in a three- or four- or five-act story structure where the story moves from one “act” to the next.

This change in definition has caused a certain amount of confusion. Most stories have one, and only one, climactic moment in which the outcome is settled. There may be many points of great tension and drama, but there is only one that is the highest point. On the other hand, there are plenty of stories that take a sharp turn away from whatever the reader had been expecting, and these do feel a lot like whipping around a sharp corner at high speed, so it’s perfectly understandable that these points end up being called “turning points,” even though they aren’t THE turning point or climax.

There is a good deal to be said for both views, if you’re a writer…and if you are a writer, you don’t have to worry about whether they can both make sense simultaneously. You only have to worry about whether the way of thinking about turning point(s) you’re currently using is currently helpful to you.

Some writers, for instance, can get totally bogged down in the miserable middle of a novel if they only ever think about the big climax they’re aiming toward. It’s too far away and it’s all uphill from where they are. They find it much more helpful to look for tense, dramatic moments of change – lesser turning points – that are closer to hand. It’s a lot easier to get motivated to write the cool scene in the next chapter where the heroine makes a life-changing discovery or finally gets the sword she needs to slay the dragon than it is to get motivated to write the battle with the dragon that’s still twelve chapters off, even if the giant dragon-battle is much cooler.

On the other hand, if all the writer ever looks at are the cool scenes that are coming up, they can easily lose track of where they’re going. It is therefore advisable to stop occasionally and ask oneself whether one is still making progress toward that big, dramatic, final climax…and if not, why not. If a new climax has presented itself, one that’s bigger and more dramatic, that’s fine; but if one is merely wandering in circles in the bog, writing lots of little “turning points” and revelations that don’t actually get the story anywhere, one may have to murder more than a few of the darlings that have been distracting one.

It is also possible for a story to have a double climax, especially if it has an emotional plot that has equal or nearly-equal weight with the action plot and the climaxes of each part can’t possibly take place in the same scene. In this case, readers will generally perceive one of the two as THE climax, but different readers will pick different peaks, depending on which plot they were more interested in. As long as they all go away satisfied, this is fine, but if the writer shortchanges the climax of one plotline because he/she is more interested in the other, one set of readers will end up unhappy. A similar problem can arise when the author is writing a braided novel with an ensemble cast, and likes or dislikes some characters or plotlines more than others.

Noticing these problems is half the battle, or more…or rather, if you don’t notice, the battle is lost before you even start. You can’t fix what you don’t realize is there or recognize as a problem. It is, however, up to the writer to decide whether he/she works most productively and effectively by doing periodic checks during the first draft, or by writing the whole thing and then ripping it apart during the revision stage, as necessary.

And of course, this particular plot structure isn’t the only one there is, though it is possible to shoehorn an awful lot of stories into this format. Next time, I’m going to talk about some of the other possibilities.