How many great novels did Jane Austen write? And other notes from Austenland

By MICHAEL CAINES

A performance, a panel discussion and a movie are what Bristolian Jane Austen fans can expect tomorrow night, courtesy of the Bristol Women's Literature Festival. To celebrate "The Glory of Pride and Prejudice" together, all they need to converge on the Watershed, where they can enjoy a performance by Kim Hicks, a discussion involving two professors, the author of Who Needs Mr Darcy? and a young Austen fan, and a screening of Joe Wright's film version of 2005. That's surely plenty to be getting on with.

And yet, for the person truly in the grip of Austen-mania, maybe not. You could spend the next few months traversing the South of England, from Bristol tomorrow night to the museum in Chawton, Hampshire, digressing to London for a spot of Austen-based improvization or (early next year) a Mansfield Park study day. By all means, venture up north for Jane Austen's Regency Christmas festival or Jane Austen's Christmas concert – just be home in time for the BBC's adaptation of Death Comes to Pemberley, won't you? You've just missed the Jane Austen Celebration Day in Lymm, but never fear; something tells me there's bound to be another excuse for celebrating Jane's fame soon.

Here's one that I'll mention as a slightly less curmudgeonly NB to my post about the Georgians (of which a proper TLS review, not by me, is coming soon): one neat touch is that the BL exhibition's copy of Cecilia by F. Burney is open at the page where one female novelist seems to have inspired the other:

"The whole of this unfortunate business", said Dr Lyster, "has been the result of PRIDE and PREJUDICE. . . . Yet this, however, to remember; if to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you owe your miseries, so wonderfully is good and evil balanced, that to PRIDE and PREJUDICE you will also owe their termination . . . ."

So now any visitor to the BL this winter doesn't even need to call up a copy of Cecilia in the rare books room to see those words jumping up and down on the page, as they would have done in the mind of the author of "First Impressions", crying out to be stamped on a title page.

The world is always interested in Jane Austen, as another professor put it in the TLS earlier this year – hence the concerts, the films, the films of genre-twisting sequels to the novels. And I'd fondly imagined that the basis of this phenomenon was a widespread admiration for six novels by a single, ingenious hand. (Unless Austen was ambidextrous.) You'll remember the one about the philosopher who was asked if he read novels, and said yes, I re-read all six every year . . . . Only now I know that he/I/we got the most basic thing of all wrong: the adding up.

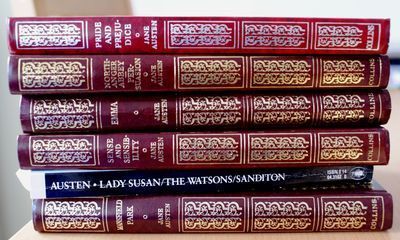

It’s not the done thing to pick on a press release – although unfortunately it tends to be the impressively poor ones that sometimes stick in the mind, either for their magnificent prose or for getting something completely wrong about the book they're trying to promote – but there's something striking about the first line of the salmon-pink sheet that accompanies Penguin’s latest reissue of the Complete Novels of Jane Austen:

“Enduringly popular, treasured and enjoyed, the seven great novels of Jane Austen, beautifully repackaged in a new hardback edition”

The seven great novels? This isn’t a claim you’ll find on the dust-jacket of the collection itself, also salmon-pink, which instead features this piece of praise from Nigella Lawson:

“Tells us wisely and wittily about the nature of romantic entanglements and the follies of being human”

The grammatical incompleteness gives the game away: it is Persuasion that Ms Lawson is singling out here, rather than Austen’s oeuvre as a whole. She places it above the others, in fact: “Everyone has their Austen, and this is mine”.

The seventh novel turns out to be “Lady Susan”, the short epistolary fiction that is more usually packaged with the incomplete works, “The Watsons” and “Sanditon”, and regarded by some as mere apprentice work, handy principally for the speculations it might provoke about the major ones. So my initial thought was that only somebody trying to sell the Complete Novels both accurately (it contains seven novels) and hard (they're great!) would try to pass off "Lady Susan" as "great". I hadn't read it for years but, actually, enjoyed it very much this time round. Then I wondered what the critics say. Many of them ignore it entirely. But those who don't necessarily dismiss it out of hand.

Of those three minor works (the other two being unfinished), for example, Margaret Drabble, calls "Lady Susan" the "earliest and possibly the least satisfactory" ("What a pity it is that she never, in her mature work, returned to the subject of a handsome thirty-five-year-old widow"). Janet Todd gives it a little more credit, in the Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen; Paula Byrne regards it as one of Austen's "experiments with narrative voice", "an important transitional work"; and Claire Tomalin imagines it could have been a better book "if its heroine were provided with an opponent worthy of her skills", but finds it "truly remarkable", all the same, for its "energy and assurance in trying out such an idea and such a character". Elizabeth Jenkins, many years ago, said:

"it contains no one character of such charm and worth that we long to read the remainder of his history; but as it stands it is a remarkable structure, comprising, within a very little space, a great deal of light and shade, and that most satisfying kind of excitement which is produced in the reader by turns of action at once dramatic and inevitable."

That doesn't sound so bad now, does it? Only don't hold your breath for a Christmas special.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers