Paul Marchesseault – The Flying Battery Commander – Part Three

The Boys of Battery B

Paul Marchesseault

Part Three

Tragedy At The Trash Dump

In one of his first letters home Paul empties his heart over the struggles of Vietnamese civilians.

My whole outlook on life is changing rapidly. The people here are so desolate and backward that I’ll feel guilty having so much when I go home. Many of the little kids over here go around naked for want of clothes. The older people look sickly & penniless. We have some working for us at the unbelievable rate of 10 piasters per hour. That’s about 8½ cents an hour. Most of them couldn’t earn 1/10th of that in a day on their own. You can’t imagine the feeling that goes through me whenever I see hundreds of locals charging across a trash dump to an army truck about to dump garbage and other trash. They swarm over the trucks like ants – fighting, pushing, & grabbing at empty tin cans, cardboard, which they use for shingles, or plain old garbage, which they sort out & eat whatever looks tasty. It’s disgusting and it’s also quite an education. Need I say more? They’re starving & we can’t do enough for them. (October 20, 1966)

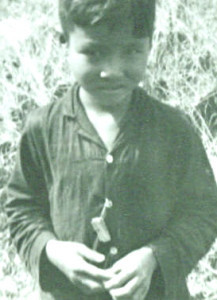

Boy Wearing a P-38 Can Opener from a C-ration packet

Later, not far from Qui Nhon, Paul would learn of a tragedy at his own trash dump outside of the B Battery perimeter.

A little kid was trying to get on our truck that was out at the trash dump. He fell off and as the truck was backing up it ran over his head – killed him. They reported it to me when they came back, and we reported it up the chain. But there wasn’t anything we could accuse the driver of. Very unfortunate incident. Joe Mullins witnessed what happened and you can ask him about it.

Joe Mullins was 20 years old in Vietnam, fresh from the mountains of southwestern Virginia. He talks of the events at the trash dump with feeling.

I was on guard duty that day, in a bunker on the side of the ridge. The garbage dump was so far away that if I had hollered they could not have heard me. There’s a bunch of children there and they was trying to get on the truck. I seen the danger as soon as the truck started backing up. As it started backing up and the kids started getting on, the truck started going faster backward, and then the driver hit the brake. It was almost like he was doing it intentionally but not meaning to hurt nobody. But you can’t keep speeding up when your looking through your rear view mirror and you see them climbing on, and then you hit your brake. I seen that if somebody didn’t get hurt it was going to be very lucky. I couldn’t holler because it was too far away.

Up until Marchesseault told me, I didn’t know the boy got killed. I always thought they just hurt him real bad. I remember a bubble helicopter landed not long after that. I have no idea if it was the colonel coming in or they took the boy out because I was at the bunker and couldn’t see everything.

Tell the truth I didn’t want to see it and I didn’t want to remember it. Because there was one thing that disturbed me in Vietnam – the children. I come up through the hard road of knocks, in the ol’ Appalachian mountains here. I didn’t live too much better at one time than what they did. I didn’t know their lives was tough because that’s all I knowed.

I didn’t always have sympathy for the South Vietnamese soldiers, but I had a lot of sympathy for the children. I can still remember a little girl that was about four or five year old when I was at Song Cau. We’d have to walk inside the perimeter for guard duty, inside the barbwire. Of the daytime the children would come down around that barbwire and guys would throw things to them out of their sundry pack. I always noticed this little girl, she’d always stand back behind the rest of the children, would never come up there. She didn’t hold her hands out or ask for nothin’. She wasn’t greedy, just stood back. I started throwing her something and learned her name was Mun. There’s no story to that. It’s just something when I first got in country.

(There will be more from Joe Mullins next week.)

Paul’s Trouble With Grenades

It happened on the single lane bridge across the river near Tuy Hoa. In addition to the flow of military vehicles there were always civilians carrying stuff, baskets on the ends of poles or balanced on their heads. Traffic across it flowed very, very slowly. The bridge had over 25 sections so you had to wait about an hour just to get your turn to cross. Every now and then Charlie would try to take out part of that bridge and occasionally he’d knock down a span. But it was fairly well guarded and kept open most of the time.

Tuy Hoa Bridge

Courtesy Jim Lord

We were the lead vehicle of a group of three military vehicles. We came up on a group of civilians, and one of them was an old woman wearing a conical hat and black pajamas. As we approached her I saw she had a grenade in her hand. I thought, Holy shit. I chambered a round in my M16 and was getting ready to shoot her. The driver saw me and said, “What are you doing, sir?”

I said, “She’s got a grenade.”

He said, “Oh, she’s just fishing.”

And sure enough, as I was about to fire she tossed that grenade over the side into the water. BOOM! Next thing you know a bunch of little kids floated out from under the bridge in woven baskets to pick up all the dead fish. I swear to god I almost shot that woman.

That’s got to be something you think about a long time.

Yeah, I did. I had another grenade incident months later on the road to Qui Nhon. The road was really, really rough. You couldn’t do more than two or three miles an hour on it in places. Marlowe, my driver, was driving the jeep and I’m just kind of relaxing, leaning back in the jeep with my M16 across my lap. I heard a klunk! It was a metal-on-metal sound and then something hit my foot. I looked down and here’s a grenade with no top on it rolling around in the wheel well. I thought, Damn, that thing’s going to explode. I yelled at Marlowe, “Get out of the jeep.” I rolled out to my right, bounced on the ground, and tore up a knee.

Marlowe stops the jeep and looks back at me wondering what the hell’s going on. What I did not know was that this was one of the grenades that we had hanging by their handles from the defroster on the windshield. It had vibrated itself unscrewed and the grenade part fell off the blasting mechanism, which was still hanging from the defroster. I thought for sure that sucker was about to blow. If we had been going any faster I’d have killed myself. Marlowe just shook his head and did his best not to laugh. I often wondered what he told his buddies after we returned to the battery.

Held At Gun Point

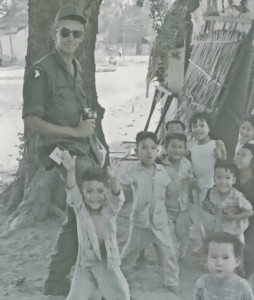

This is a picture of one of my enlisted men standing with some young kids who were around our barb wire in Song Cau all the time begging for candy and cigarettes. He came to us directly from Mannheim Prison in Germany by volunteering for combat duty. He was in jail for burning down a government warehouse after receiving a Dear John letter from his girlfriend in the States. She had just joined a convent. Lo and behold he landed in B Battery.

Lucky you.

Lucky me. He was an all around jerk, a lazy son-of-a-bitch who couldn’t keep his gear in order and a poor soldier. He was often in trouble and found himself pulling extra duty as we as we moved up and down the coast. We’d been in a place called Binh Thanh for several days, just a little north of Song Cau. Once again, he was on some kind of extra duty; I don’t remember the details, except that he was pissed.

I had a hex tent located half way up this hill and away from everything else. I was alone in my tent when I heard a guy outside call me by name. “Captain Marchesseault, can I come in and talk to you?”

I said, “Yes.”

In he comes and he’s got his M16 with him. He pulls the charging handle and chambers a round and points the weapon right at my chest and says, “I’m going to kill you.”

I’ll be honest with you, it frightened the hell out of me. I pleaded, “Hold on. What’s going on? Let’s talk about it.”

I started to get out of the chair I was in and he yelled, “Sit down!” And so I sat down. He started going through a list of his complaints, that I had been so hard on him. He couldn’t take it anymore. And since I was the cause of his problems he was going to kill me. I tried to tell him, “Hey, you do it to me, you can’t kill the whole battery. Somebody’s going to get you and you’re going to end up in prison again.” You could see that this guy was a nut case.

While I’m talking with him, trying to get him to calm down, First Sergeant Shepherd comes strolling up the hill and hollers, “Captain Marchesseault, can I come in?” He doesn’t know what’s going on inside. Before I could answer, Shepherd comes in. Our boy turns the gun on him and tells him to sit down, and he sits down next to me on my ice chest.

Shepherd was a lot calmer about it than I was. He convinced this young man that all he really needed was a break and that he’d get the rest he needed. Shepherd told him he’d probably be able to go on R&R if not just a rest at a hospital, and we both promised to send him to the rear. He didn’t take long to think about it and handed Shepherd the weapon. Shepherd took the magazine out, cleared the round out of the chamber, and walked him down the hill. I never saw him again. The Military Police evacuated him to Tuy Hoa and later battalion sent him somewhere for psychological analysis. I don’t know what happened to him. I suspect he was treated as a Section 8 mental case. There was never a trial or anything. I remember discussing it with Colonel Munnelly – about why he was sent back to the rear, and Munnelly understood.

Ernie Dublisky remembers the young man in a different light, one that softens the picture that Paul carries in his memory. “When I was battery commander before Paul, the young man was in supply back at battalion. I knew he had come from prison in Germany. The story was that when he got the letter from his girlfriend he was very upset and asked to be excused from guard duty. His sergeant refused the request and that was when he retaliated by burning down the supply depot. I remember that he always tried his best to get us the supplies we needed. He seemed to me a hard working and sincere young man. I guess the strain in the field got to him.

The effect on Paul went beyond the hour he spent looking down the barrel of an M16.

The kid really shook me up. Munnelly came up for a visit and realized I was still a bit rattled. He said, “You know what, you need a break too.” He ordered me to go on R&R, which I had not planned. But I was able to get a message to my wife and she was able to get a flight and meet me in Hawaii.

The day I left a guy picked me up in an H-23, a three seater helicopter with a bubble nose. The pilot sat in the middle seat, with a person on either side of him. The helipad was way up on top of the hill, and as soon as we took off the engine sputtered then conked outsome 500 feet in the air. We just auto-rotated (rotor blades disengaged from the engine, allowing them to spin from the downward fall and thus helping to slow the descent) into the swamp right in front of the battery position. (Laughs) I figured I was never going to get out of the damn battery area the way things were going. Somehow the pilot figured out what was wrong and got it going again. So off we went.

A Nice Bookend

Coming back from Hawaii I flew into Cam Ranh Bay, where they told me I’d have to take a jeep or a truck back to Binh Thanh. This was a ride of 125 miles on terrible roads that would take three or more days and require permission to move from strong point to strong point through areas controlled by the South Koreans and ARVNs. Instead I was able to hop on a Caribou cargo plane that was going to An Khe, which would get me most of the way. On our approach to the An Khe airstrip the pilot warned us that the nose landing gear might not be locked down and that we could have a problem. He landed us tail first with the nose up in the air and rolled as far as he could before letting the nose settle down. Sure enough the landing gear collapsed and we nearly flipped over. A nice bookend to the helicopter decent into a swamp a few days earlier that began my Rest & Recreation.

The Mad Minute

Sometime after my R&R in Hawaii we moved the battery further north to a hill at Xuan My. This was the last move for B Battery with me as the commanding officer.

When Munnelly and Dublisky handed B Battery over to me it was a smooth running machine. Morale was super high and we had a great crop of NCOs. That’s probably one of the reasons Munnelly did not hesitate to have me keep flying. But as guys rotated out the new people they brought in were not as skilled as the guys we lost.

We stayed at Xuan My too long as far as I was concerned. Guys were no longer used to picking up and moving, to having everything where they needed it at the right time – weapons were not being cleaned properly, people were forgetting things. And it had been quite some time since the battery had been hit and I felt that people were becoming lax. You’d find things that were screwed up and people would make excuses for those screw-ups. I was really concerned.

So I got together with my exec, a few NCOs, and the commanding officer of the Koreans who were our perimeter security. We drew up a plan to simulate a night attack while most of the battery was asleep. I wanted a lot of noise all at once to jar people awake. So every manned piece of equipment we had started shooting at the same time. We fired the H&I gun, all of our perimeter machine guns, a handful of M-16s, our Claymores, the fougasse barrels the Koreans had dug into the hill side, everything.

I arranged to have this damn thing kick off at 4:00 in the morning, and I had positioned NCOs out at observation posts to make sure there were no screw ups. My chief of smoke fired a single flare into the air that set the thing off. We fired for about five minutes; the machine guns firing until three out of four jammed. And it worked: the troops thought we were under attack. And then we had a critique the following morning.

When Munnelly heard about it I thought I was going to get in trouble. I think he heard about it through the Special Forces who wanted to know if one of his units had been hit the night before. The Sneaky Pete’s (Special Forces Rangers) who were a few miles out in the swamp in front of us didn’t know what was going on. They must have thought, Jeez, how do we get these guys help? So when I found out that Munnelly was pleased, that made me feel a hell of a lot better. I thought I was going to get in trouble. I did meet with the Special Forces team and promised to give them some warning if we ever did it again.

Col. Munnelly told me you started the Mad Minute.

I did. It was my idea. Because of the things I had seen going on. I just said, “We’ve got to sharpen these guys up.” And it woke up a few of them, I tell you that much. Our overall readiness improved a bunch after this stunt. But that was the only time I ever did it.

It continued after your time. It became standard procedure once a month. When the howitzers and machine guns were going off guys would go out to the berm and fire off their M16s. It was party time.

Wow. I did not know that. Of course our purpose was to make sure nobody knew it was going to happen ahead of time. You could only do that once.