'Ali and Wallo watch The Wire': excerpts from 'Sorry For Partying' – a Novella

For Ali and Wallo, being young lovers meant having sex, drinking, eating stir fry, and watching The Wire.

For Ali and Wallo, being young lovers meant having sex, drinking, eating stir fry, and watching The Wire.'Ali and Wallo watch The Wire': excerpts from 'Sorry For Partying' – a Novella by Tessa Brown | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

For Ali and Wallo, being young lovers meant having sex, drinking, eating stir fry, and watching (re-watching) The Wire. On what was beginning to seem like more nights than not, they could be found in Ali’s Pilsen bedroom, discussing the representational merits of the cultural text at hand. Despite its near-perfection, The Wire still had some faults.

“How come the black women are all lesbians and hookers?” Ali asked. She reached for her whiskey beside the bed, where it was sweating on a stack of unused LSAT study books.

“There was that black lady crackhead,” Wallo offered.

“And what about the white dudes? We’re all buffoons?”

“Yes,” said Ali. “It’s making a point.”

“That the writers hate white guys?”

Ali took a sip of her drink, then lifted her chin for the stump speech. “That white supremacist patriarchy is morally bankrupt and overly invested in phallic displays of power.”

“I’ll show you a phallic display of power.” Wallo grabbed her around the waist. Ali giggled. On the screen, said black female lesbian and white male buffoon prepped a crackhead snitch while a bunch of young bucks loitered in the background, cleverly visible through their police car windshield.

Watching with Wallo was hard enough, given that Ali had already seen the full run in high school when the debut of an epic drama about Baltimore’s criminal justice system was reason enough for her father, a Baltimore lawyer previously opposed to cable television, to splurge for cable so that he could watch The Wire with his wife and his daughter every Sunday until she left for college. On first watch, the show had been a revelation, a careful charting in narrative of the complex systemic failures that lent the Jacksons’ Baltimore existence its peculiar post-apocalyptic flair. But now, the second time around, laying half-drunk in bed with Wallo, Alison felt painfully aware that the men and women on the screen before her were actors, successful actors, performing what for many of them was as foreign a dialect as Shakespearean English.

“This is not the real criminal justice system,” Ali said to the ceiling.

“Ceci n’est pas un crack pipe,” said Wallo. “But it’s enough for an arrest!”

English, Ali thought, as she and Wallo stood waiting for the bus the next morning, was not exchanged daily in the measured, rolling tones articulated by even the most grisly of junkies on The Wire. Why, even right here, on an arbitrary corner of south-central Chicagoland, at one of what must have been tens of thousands of bus stops city-wide whose waiting denizens’ ancestors once spanned the globe, the heaving vicissitudes of language were as apparent as in the Cross-Cultural Linguistics textbook Ali had studied as a sophomore in college. Beside her, a woman was yammering into her cell-phone in rapid-fire Spanish. Ali tried not to listen but certain English words—iPhone, data plan—stuck out even above the rush-hour din. Unlike actors, real humans, from the meanest on up, dispensed language like a gooey soup over whose original ingredients speakers had little control. Behind her, Wallo stood with his headphones on, impervious to the teeming masses jostling past them on the sidewalk and jockeying for first place onto the anticipated bus.

For a year she’d waited for this bus with Carmen, not Wallo, and together they’d parsed these streets, this Chicago life. They’d made themselves meaningful together. It was Carmen who’d taught her about syncretism, a concept he’d studied at Oklahoma State. Syncretism: that despite colonists’ best efforts, cultural exchange flowed in two directions. English, Carmen said, wasn’t an Emperor who came to a foreign land and replaced all the laws; no, English was the blankets brought by the Emperor’s men, distributed to the people one township at a time. Her job, and Carmen’s, was to minister these people’s children, to monitor their blankets for holes, lice, unraveling, help them embroider it or sew on patches if they wanted to but mostly make sure that when these kids ventured out into that cold, bitter Anglophone world, that they were protected, and that the gatekeepers would recognize their clothes.

The bus pulled up before them, a heaving iron mammoth bouncing back on its heels. The doors pushed open like a jaw, waiting for some morsel to crawl inside. This bus wanted company more than anything. Wallo waded forward toward the back of the bus, his messenger bag firm against his back. Ali followed carefully. She sidled sideways, struggling to keep her tote behind her instead of bumping the seated passengers’ heads. They sat down across from each other in the raised section toward the rear.

Next to Ali, a Black woman was chiding the man sitting next to her. “Honey, I done told you,” the woman said. Her coat was pulled closed, and her purse sat firmly on her lap. “Them lines won’ fly.”

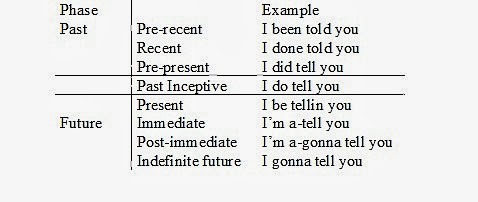

“Baby, you ain’t said nothin’ of the kind,” the man said. Ali tried to watch them from the corner of her eye. The man, with his gentle insistence against the woman’s stony front, was clearly coming on to her. Ali wondered if they were friends. Or maybe they’d just met on this bus, ten minutes ago. Had the woman said been told or done told? That would give a clue. A linguistics table floated between Ali’s eyes, somewhere over Wallo’s head, a lexicon she’d studied years ago.

Ali remembered cramming for a quiz on verb tenses and phases in her African American Vernacular English course, struggling to stay focused through the honey-thick irony that threatened to suffocate her will. Even now, years later, the absurdity of it still stung. She imagined her ancestors (slaves, of course, though she preferred not to think of it), bug-eyed at their upper-middle class scion with her gratefully pale skin, daughter of homeowning professionals, an honor student at the nation’s finest Historically Black College for women, Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, studying some backcountry, field-hand vernacular and callin’ that book learnin’?! Now that was the white man’s devilment if there ever was. In all Ali’s years as a Linguistics major that was the course in which she had fared the worst. While some of her classmates had snickered behind dark hands at seeing their discarded verb forms canonized in a textbook, Ali had never spoken this vernacular tongue at home, had certainly never wished to ‘til now. Struggling with been’s and done’s and did’s, she’d never felt whiter than she had studying for that low-down test.

Across from her, Wallo grinned, a big guileless dude of a smile. Oh, brother, Ali thought. What kind of a quicksand is this?

***

Tessa Brownis a PhD student in Composition and Cultural Rhetoric at Syracuse University, where she studies hiphop composition pedagogy. Her novella "Sorry For Partying" was a runner-up for the 2013 Paris Literary Prize, and you can read it all on Medium. Hit her up @tessalaprofessa.

Published on November 16, 2013 14:26

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.