Paul Marchesseault – The Flying Battery Commander – Part Two

The Boys of Battery B

Paul Marchesseault

Part Two

Ten of Paul’s letters survive. He wrote them to an older brother with the intention of being candid about the war, and with strict instruction not to share them with his wife or parents. He had been flying just five weeks when he wrote on November 19, 1966:

I get tired of telling everyone at home that all is quiet and the VC are being nice little boys. It’s quite far from the truth. The “graves registration” office is about 300 yards from us & they had a very busy week. So did I. I had 13 flights in the last 9 days. I now have over 50 hours in the air since the 10th of October.

The flights themselves are fun, until I think of where the hell I am. I feel even more jittery in a helicopter. In those H-13s we have no armament whatsoever & only a big plastic bubble around us. No, it’s not bulletproof. Stewart Alsop said recently in “Post” magazine that “If you ever want to feel like a quail during hunting season, fly over VC territory in an H-13.” Guess what, he’s right! I wonder how he knows. Yesterday we got caught in a rain squall in an H-13 and ended up flying 15 miles about 10 feet off the ground at 110 mph in Charlie territory. It makes the old rear end pucker up.

Here’s what an H-13 looks like:

If & when I’m through flying I’ll probably let them know. I’m getting sick of writing the same old crap every day. I’ll let you know if & when I do let the cat out of the bag.

Three weeks later he took command of B Battery.

Letter of December 29, 1966

First we moved about 20 kilometers north of Tuy Hoa to a place called Tuy An in support of the 47th Vietnamese Regiment (ARVN). We camped on a hillside from the 15th to the 22nd & chalked up about 55 kills, 6 sampans and an untold number of wounded. The people we were supporting suffered 9 killed and 17 wounded.

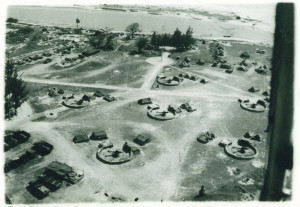

On the afternoon of the 22nd my entire battery was airlifted by giant Chinook (CH-47) helicopters into the village of Song Cau. I came in on a small helicopter and directed 16 Chinook loads into the area. We are now 63 kilometers from our battalion and can be resupplied only by chopper.

The village itself is small (pop. 400) & the principal industry is lobster & shrimp fishing. The village is in a small valley near the sea and surrounded on 3 sides by mountains. Currently 2 VC battalions are known to operate in these hills. We were no sooner on the ground when we fired at the VC & we’ve fired over 4000 rounds at them since we got here.

Our battery position is in the middle of an athletic field next to the village grammar & high schools.

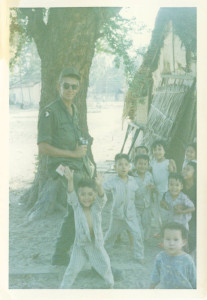

Picture Included in the Letter

On the day before Christmas, I got the district chief who speaks some English to accompany me to the grammar school & we passed out a case of assorted candy that had been collected from the men in the battery. You should have seen the faces on the kids. They’ve never seen Americans in any number before and they went wild. They sang for us off & on all day right next to our position. That night (Christmas Eve) they had a big candlelight procession through the town that was very pretty. They even sang Silent Night, Hosanna In Excelsis, & other hymns in Latin. It reminded me of the old days at Assumption.

Included in the letter is a picture of a soldier standing among the children.

That soldier would later hold Paul and his first sergeant at gun point for an hour, threatening to kill both of them. (That story to appear next week in Part Three)

In the meantime, Paul himself could be dangerous with a gun.

Nearly Shooting My FDO in the Middle of the Night

In Song Cau I had a conical hex tent, and in the tent I had a little spring bed, a work table and a trash can, which was a five gallon potato chip can. It seemed like every other night I’d hear scratching around. The damn rats would get into that can looking for stuff. I had a .45 under my pillow. One night I heard that thing scratching away and I was just about to shoot the trash can which was near the opening of the tent, when I saw the face of my Fire Direction Officer, Tommie Malone. He had come into my tent to tell me he needed me in the FDC. He had to pull up the tent flap to get in and came in leaning over. The trash can was only two or three feet from his head where I was aiming. If you talk to Malone he’ll tell you he was looking right down the barrel of my .45. He thought I was going to shoot him.

Tommie Malone Eating Lunch

Today Lieutenant Colonel Tommie Malone has that .45. The story of how he came to own it begins in Germany.

I knew when I was in Germany that I was going directly to Vietnam. I was not going with a unit; I was going over alone.

I had a friend who was a member of the Munich Rod and Gun Club. He introduced me to an enlisted man who had a customized Army .45 for sale. It was a special gun. Normally a .45 had plastic hand grips; this one had carved wooden grips. A regular .45 was a dirty grey; this one had special bluing, a nice steel blue weapon. The slides had also been modified for it to fire more smoothly. I test fired it and that thing was accurate as hell. It was a fine weapon.

I bought it just before I left Germany and took it with me to Vietnam, which you weren’t supposed to do. I broke a rule. Whether I violated a military regulation or not, I don’t know.

When I got into Saigon there were only two officers on the plane, me and Bill Manning (who was about to be named battalion Executive Officer). The customs MPs took us aside to examine our bags and told us to declare any weapons we might be carrying. I admitted I was carrying the pistol and it was immediately confiscated. I thought I’d never see it again but happy the MPs hadn’t given me any grief over it.

I was then sent to the 5/27th battalion base camp in Phan Rang for in-processing. A couple of days later I was flown up to Tuy Hoa, where I reported into Colonel Munnelly. As I saluted him I spotted my .45 right there on his desk. It was easy to recognize. I figured the MPs had given it to Manning, and that’s how Munnelly got it.

The first thing out of the colonel’s mouth was, “Boy, this is some start, captain.” He was acting angry. “This is some hell of a start. You violate a rule before you even get here.”

I was standing there at attention, expecting to be welcomed by the man who’s going to be my boss for the next year, and all of a sudden I realize I’m in deep shit. After he calmed down he said, “We have no point in keeping this here in the battalion. Since you’re going to have to draw a .45 anyway – here, use this.” And he handed me the pistol.

Then he eased up a little and talked about the battalion and the job I was going to do. But I still thought I was screwed. I thought I was going to get an Article 15 (non-judicial punishment) the way he was going at it over that pistol. He could be angry when he wanted to be and I felt uncomfortable in his presence for some time to come.

Were you able to bring the .45 home?

No I did not. I was concerned about it when I left, all the crap they were giving us about taking things home. I sold it to Tommie Malone.

Years later I located Tommie via the internet. He was still in the service, had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was then head of the ROTC program for the San Antonio schools. We had dinner, with him and his wife, Rena. The subject of the weapon came up that evening, and he said he still had it.