Why do history?

Last night was a big one for me. I went to the Grierson documentary awards -- where I presented the award for the best history documentary to The Secret History of our Streets (Deptford High St), and was then justly beaten by Grayson Perry for the documentary presenter of the year award.

Actually, by the time Grayson was steppng up to the podium, I was several miles away at the presentation of the Samuel Johnson awards, for which I had been a judge (told you it was a busy evening).

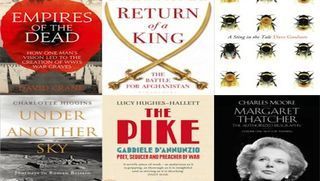

You can see the six excellent books above -- everyone of which was really damn good; but Lucy Hughes Hallett was the eventual winner, for her biography of D'Annunzio (do read it, and the rest).

It ws a wonderfully good tempered and celebratory evening. And if there were disappointments (which of course there must have been) they were very generously kept in check -- in favour of a great party to give non-fiction a boost in all its forms.

But what of the choice? Someone did say to me in the course of the evening, "wasnt this shortlist a bit weighted towards history and the past?". That was actually quite an easy one to answer. For, it's only on certain narrow definitions that history is really locked in the past.

Dalrymple's book, for example, asks us explicitly to think about the links between nineteenth-century and more up to the minute western incursions into Afghanistan (message drawn by me: never invade Afghanistan). Higgins also directly links the past and present, asking how the Roman Britain still mens something even now.

And Lucy Hughes Hallett resonates in the same (if slightly less direct) way. One question her book raises concerns how we make our political judgements. Or -- to put it another way -- how do we deal with political leaders whose repellent policies don't always match their personal charisma or charm? D'Annunzio was clearly awful, in all kinds of ways; but he still commanded the love and admiration of many --and not just the stupid, or the proto-fascists (though there were plenty of them).

His lesson (to a modern world which wants easy black and white) is that we should think more carefully about our political leaders, whom we meet in many different mixtures and guises. Virtue doesn't come as a simple package (some of the most politically saintly, are personally awful -- and vice versa). So to take a pretty crude example: I have only met Nigel Farage once. I utterly abhor his politics (without saying that I think that he is a D'Annunzia style fascist -- far from it), yet I remain grateful not just for his courtesy on that occasion, but for his care in bringing me into the conversation, being a thoughtful dinner companion etc etc.

Now, I know there is an old, tired and silly cliché about Hitler loving his pets etc. But one of the things that The Pike makes us reflect on is how and why we admire those we do, and what for -- and how villainy and virtue don't come neatly wrapped.

It would be so much easier if they did -- but, given that they don't, it's a good idea to understand the messy, complicated mixture of good and awful evil that D'Annunzio represents.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4112 followers