Souls, Saints, and the "Permanent Things"

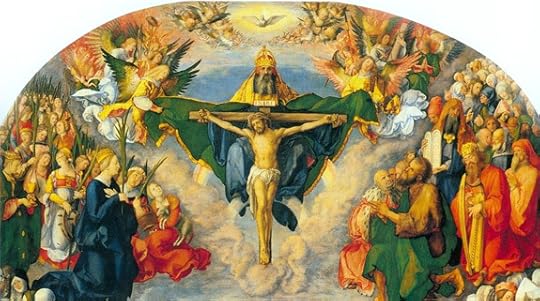

All Saints picture ("Allerheiligenbild") by Albrecht Durer (1511)

Souls, Saints, and the "Permanent Things" | Fr. James V. Schall, S.J. | CWR

We are in danger of losing contact with the dead in our families and in our culture

I.

A seminary in Ireland,

now closed, was dedicated to the training of priests for foreign missions, for

strange places such as California. It was called "All Hallows", that is, All

Saints, November 1. Oxford University in England has a college called "All

Souls," November 2. Taken together, all saints and all souls are designed to

cover all of the final combinations of the human race except all the still

living, who are waiting to join one or the other of the previous categories.

Come to think of it, all "all saints" all have souls. What are left are all

lost souls who, presumably, have already also made their final choices about

how they are permanently to be.

Most of my relatives are buried in the Catholic Cemetery

just at the edge of Pocahontas, a small county seat in rural northwest Iowa. My

mother's grandparents, my grandparents on both sides of my family, my mother

herself, and, I believe, all but one of her thirteen brothers and sisters are

buried in this neat cemetery. Two of my father's brothers are also there; his

other brother is a few miles east in the cemetery in Clare. Two of my father's

four sisters are buried there, as well as numerous cousins and their families,

though many are scattered in later years. My own father is buried in the

cemetery in Santa Clara, and my brother in the cemetery in Spokane.

On the Second of November, many families, especially in small

towns, decorate the graves with flowers, have Masses or prayers said for their

deceased relatives, and in general remember them. In modern cities, I think, we

are in danger of losing contact with the dead in our families and in our

culture. Families move. Cremation changes things. There are so many of us. We

do not have to be superstitious, of course. We believe in the immortality of

the soul and the resurrection of the body. Our contact with cemeteries is

designed to recall our very mortality, but also to remind us of what we hold

about death and its place in our lives.

As we get older, we find that many

more of our immediate family are dead than alive. We find friends gone. Such is

our lot. To wish it otherwise, while not a totally unhealthy exercise, needs to

be understood clearly. It is given unto every man once to die, thence the

judgment, as it says in the Book of Maccabees. Death has become a hospital, not

a home, thing. The dead body is a source of parts, to be somehow passed on to

others. We think almost exclusively of the living, not of the dead.

We celebrate lives at funerals. We

do not worry about souls and their fates. The elderly are a problem, even a

social and political problem, not sources of wisdom. Cemeteries are often

desired for the land they take up. Laws exist about how long cemeteries are to

be kept intact. We still notice that many Latino and Asian families somehow

take care of their own elderly at home, whereas with others this care is often

passed on to various institutions and specialists. This may not be all bad, but

we should reflect on it.

II.

Belloc's wonderful book, The

Four Men, describes a walk he took in the

English county of Sussex, from October 29 till All Souls' Day, 1902. As the

four walkers reach the end of their walk, the old man, who, like the other

three walkers, is Belloc himself, makes the following memorable farewell

reflection:

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers