Other Worlds (3)

My first of these three posts discussed the three classic fantasy worlds I grew up reading and loving: Narnia, Middle Earth and Earthsea. In my second, last week, I talked about a variety of more recent fictional worlds. In this post I want to ask the simple question: why? What’s it all about? Why bother to invent a world, anyway? And are all fantasies equal, or are some more equal than others?

For aren’t fantasy worlds merely the fictional equivalent of theme parks? Places where you can go to see the dragons? Easy options on the writers? All you need is a few mountains – let’s call them the Eversnow Range; a deep and dark forest – Dimhurst, perhaps, or Tanglewood; a city on a hill – Goldthrone, or Valiance – oh, and a river to join them all together – and you’re away. You people the place with a pseudo-medieval society operating on feudal principals, with peasants, thieves, soldiers, lords and a king – shake in supernatural creatures of your choice, and stir.

Unfair? Yes, terribly; and no, not at all. This is the generic world Diana Wynne Jones christened Fantasyland. And if any of you have missed out on her brilliantly witty and razor-sharp book mapping out the many, many clichés of fantasy – why, for example, the place is infested with leathery-winged avians, why visits to taverns nearly always involve brawls, and why so much stew is consumed – you need to read it. It’s called ‘The Tough Guide to Fantasyland’: strap on your sword, pull on your boots and don that cloak: your quest is to go out and find it – now. (At the very least, if you are a writer, it will encourage you to provide your characters with a more varied diet.)

I’m thinking aloud here. A fantasy world can have some or all of these components and be brilliant – or it may be really stale and clichéd. These things by themselves are not what fantasy is really all about. They are only the trappings of fantasy, and often pretty threadbare too.

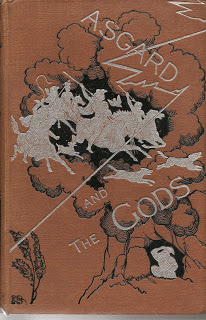

Why should most fantasies describe medieval-style worlds? I'm not saying they shouldn't: but why? Is it some kind of nostalgia? Why should swords be considered more picturesque than guns, when both are designed for killing people? If ‘picturesque’ is really all we are aiming for, we have no business writing fantasy at all. The medievalism of most modern fantasy worlds is due to the influence of Lewis and Tolkien – both medieval scholars, both steeped in the worlds of Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, and the Norse mythologies – heavily filtered through late Victorian romanticism. (Of course they could both read the Eddas in the original, but we know of Lewis in particular that he first encountered the Norse legends as a boy, probably in a book looking something like the one pictured above - wonderful, isn't it?) And the Morte D’Arthur and the Faerie Queene are themselves exercises in nostalgia and romantic yearning for a golden age of chivalry that never was. Malory was writing at a time of fierce civil war in England – the Wars of the Roses – and there’s a picturesque name for a nasty conflict. Arthur unifies Britain, then things fall apart: treachery overtakes the Round Table: Arthur dies.

Yet some men say in many parts of England that King Arthur is not dead, but had by the will of our Lord Jesu into another place; and men say that he will come again, and he shall win the holy cross. I will not say that it shall be so, but rather I will say, here in this world he changed his life. But many men say that there is written upon his tomb this verse: HIC IACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM REXQUE FUTURUS.

This must have been cathartic stuff, back in the bloodstained fifteenth century. It still is! And then Edmund Spenser was as much engaged in national myth building as telling a story: Queen Elizabeth I as Gloriana: Tudor England as a European power. And Wagner’s Ring cycle was part of 19th century German nationalism... Smaug owes so much to Fafnir.

I really have nothing against medievalism in fantasy per se: my own first three fantasies, the 'Troll' trilogy, are set Viking Scandinavia; and the fourth, Dark Angels, is set in the late 12th century. I loved and love Malory, Tolkien, Lewis, the Eddas, The Faerie Queene, The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, the Narnia stories, almost anything by Robin McKinley, and so on and on. But these are stories, these are writers, who have something to say: something they throw their hearts into, something worth listening to even if in the end we don’t agree: because it’s sincere. Medievalism by itself is not enough.

There are badly written, badly conceived fantasy novels – just as there bad novels in other areas of fiction – which have given the genre a reputation for puerility, superficiality, escapism. The ingredients are the sword and sorcery clichés: blond warriors with bulging muscles and magical swords, scantily clad nubile princesses, evil dark lords, bald executioners, battles to save the universe or at least the world, yawn, yawn… together with a giveaway coarseness of imagination, a lack of subtlety and moral depth: a readiness to assume that one side is right and the other wrong regardless of how they actually behave. Thus in some fantasies, ‘heroes’ can perform feats of sadistic violence which readers are invited to admire – so long as the victims are labelled evil.

It may seem harmless, but I find this type of fantasy with its warped values especially disturbing when aimed at children and young adults, and it seems to me that the fantasy setting is used as an excuse. “It’s not real,” we might imagine the author and publisher arguing: “it’s just a fantasy!” The same kind of thinking takes children to visit the London Dungeon, a tourist attraction which makes entertainment out of ancient instruments of torture. Because it seems ‘old fashioned’ and long ago, it’s somehow not real. The owners wouldn’t dream of lining up busloads of schoolkids to see tableaux of waterboarding or electric wires being attached to the genitals – but thumbscrews and racks are all right, apparently. Because no one really believes. No one uses their imagination sufficiently to understand that these things aren’t quaintly historical, but instruments of appalling cruelty.

So when shouldn’t we write about fantasy worlds? Well, we shouldn't be writing fantasy if we think using heroes and dark lords and dragons is an easier option than coming up with living, breathing characters. We shouldn't be writing fantasy if we think it's an easier proposition than researching a genuine historical period. (It may be harder, coming up with a coherent world, from scratch!) Fantasy shouldn't be fancy-dress.

And when should we be writing fantasy? When that is the way the truth shows us it wants to appear. When, as in poetry, there is no better way of saying what needs to be said. When a story needs a dragon, not as a tired plot device or something for the hero to slay, but as a being which incorporates beauty, terror, greed, destruction, ancient knowledge – or even, as in Chinese legend, good fortune, harmony, the Tao - when this that dragon appears in all his fiery glory, we will apprehend something about the world in a more vivid, more complete way than we ever could without him. Symbols are not there to be reduced to their meanings, they are there to enhance meanings, to help us understand the world more fully and to see it anew. And this, to my mind, is what fantasy is for, too.

Picture credits:

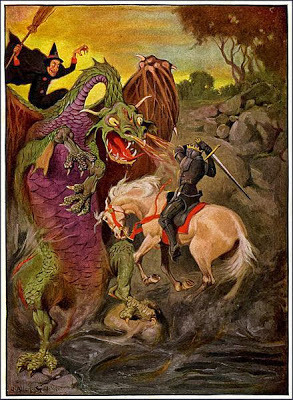

Knight fighting dragon: Frontispiece to chapter 12 of 1905 edition of J. Allen St. John's The Face in the Pool, published 1905 Wikimedia Commons

Asgard & the Gods, photo, personal possession of Katherine Langrish

St Margaret with dragon: detail: Schaezlerpalais Predella mit Heiligen, Bartolomeus Zeitblom, Wikimedia Commons

Published on October 24, 2013 03:23

No comments have been added yet.