Is Persistence Always a Good Idea?

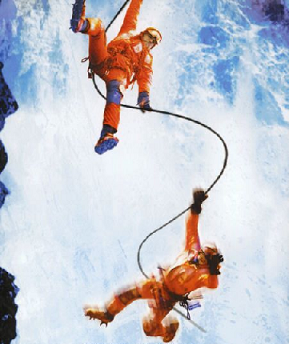

In May 1996, thirty four enthusiastic climbers were ascending the Mount Everest. Many of them were adventurers with no previous 8,000m experience, and so they hired two expert mountaineers to lead the expedition. The huge number of climbers caused route bottlenecks and delays. Climbers, however, got so locked in their lifelong dream of submitting Everest that they continued to make their way up ignoring the snow storm that was looming, the supplemental oxygen tanks that were running out, and the darkness that was falling. The result was that eight of them died and two suffered severe frostbite in what was considered one of the deadliest disasters in Everest’s history.

We’ve always learned about the virtue of persistence in so many success stories of politicians, military commanders, business people scientists, artists, athletes and the like who fought failure, rejection, or other adversarial conditions, and relentlessly kept trying till they paved their rough road to success. Persistence is known to be a quality of highly effective people who have self-efficacy and believe in their ability to accomplish their goals, but tragic incidents like Everest’s pose an important question: is it always a good idea to stubbornly pursue a goal even when signals all through the way are telling you otherwise?

In his book “Destructive Goal Pursuit”, Christopher Kayes attempts to answer this question, by warning about the dangers that stem from the combination of: 1) too narrow goals that limit the adaptability of teams or organizations, 2) shifting environments that could make the original goals not viable or unrealistic, 3) grandiosity of leaders that make them oblivious to the reality of their situation, and 4) over dependence of the team members on their leader to the extent that they might suspend their own judgment. With such lethal combination, persistence to achieve goals turns into “gambling” with resources, reputations, and perhaps lives. In the remainder of this article, I’ll try to draw the fine line that assists you to see where persistence stops and gambling begins:

Recognize and avoid “escalation of commitment”:Irrational escalation of commitment is a known decision making error that occurs when the decision maker chooses to commit more resources (money, effort, time, etc) to an initiative or a project despite the objective evidence that continuing this initiative is unwise. A classic example of this error was when the British and French governments chose to continue funding the joint development of the supersonic jet “Concorde”, even after it became no longer feasible economically. Industry experts estimated that in 2003, when the last aircraft in the fleet was retired, British Airways was losing $1,200 on every passenger who took the Concorde. The question that pops up now is: Why decision makers, no matter how experienced, continue in the wrong direction even if it is becoming more obvious that it is wrong?

There are many reasons why escalation of commitment happens. The most important of which is the attempt of the decision maker to protect his image for if he admits that his original decision was flawed, people may start to question his judgment, consistency, or competence. So, he tries to put more resources into the failing initiative hoping to make it work. Another reason is that when decision makers receive positive feedback about the performance of their initiatives, they tend to stay risk-averse in order to maintain their gains, but when things change and they start receiving negative feedback, they tend to take high risks as an attempt to prevent loses, thus they escalate their commitment.

It also is worthwhile noting that voters penalize public officials if they switch their previously supported views. This is what happened to the democratic candidate John Kerry in the 2004 U.S. presidential election when he changed his stance on several issues including the Iraq War, and this is another reason why decision or policy makers tend to stick to their views even after they become aware of their pitfalls.

Recognizing this type of decision biases and its reasons can surely help you avoid it. Moreover, here are few measures that can serve as an antidote. They are based on researches conducted by Wharton University of Pennsylvania, and recommendations of Mathew Hayward in his thoughtful book “Ego Check”:

- Remember that flexible leaders know their limits. Put advance limits for your commitment to a particular course of action and stick to these limits. For instance, you might consider going up to 20% over budget for a stumbling project to turn it around, but then you will abandon it when the spending reaches that limit.

- Don’t be authoritarian. Consult others and have someone on the team to play the role of the devil’s advocate, who looks for disconfirming or discomforting information that can help develop a more balanced and realistic view of the situation.

- Anticipate the consequences of your decisions on the organization or the team. Ask yourself: “Would I choose to put more resources into that project if it wasn't me who initiated it?” An honest answer to that question can help you make sure if it’s the welfare of the greatest number of people, not your ego or hubris, that motivates you to continue pursuing a given course of action.

- Set flexible goals for your team whenever possible, and empower team members to use their own judgment. This will allow them to quickly adapt to changing circumstances without wasting too much time and effort continuing in a direction that has become no longer valid.

- Structure your reward system so that decision makers in your team are not punished for inconsistency, especially when they are facing novel situations. This will discourage their potential to commitment escalation.

- Move the decision making authority on whether to commit further resources to ongoing initiatives to different decision makers than those who made the original “Go” decision. This will also help mitigate any personal bias.

Beware of the “sunk cost” trap:Haven’t you ever told yourself “I’ve invested too much money or spent too much time on this project to quit”? Guess what? This is a flawed argument from a rational economic perspective, yet people still make it all the time! This is called the “sunk cost” fallacy and is another way decision makers make bad decisions by continuing to mobilize more resources into a direction that evidently turned out to be less feasible. By definition, sunk cost means a cost that was incurred in the past and became irrecoverable, and hence must be irrelevant to justifying future investment decisions.

It’s interesting to see how the concept of sunk cost extends to different areas of our lives: We watch a dull movie because we already paid for the tickets, we wear unfitting clothes because we already bought them, and we maintain unfulfilling relationships because we’ve spent long time in them, and so on.

To better understand the sunk cost fallacy in business context, take this example: $10 million have been spent in building a manufacturing facility, and it’s half way to completion (i.e. another $10 million is needed to finish construction). But due to accelerated development of manufacturing technologies, an equally viable, but much cheaper alternative technology has emerged, that you can choose to abandon construction of the current facility (which can’t be resold), and build a whole new one for a total of $7 million.

The rational decision here is the one that yields the greatest payoff, which is to abandon the existing facility and build the new one, even if means a total loss of the originally spent $10 million that will be considered a “sunk cost” in that case. However, many decision makers will be mistakenly influenced by this sunk cost that they will choose to continue the construction of the current facility. The reason behind such poor decision is our natural inclination to avoid the feeling of loss, or what’s called “loss aversion”. Research has proven that people feel greater harm by a certain loss than the joy they feel by obtaining an equivalent gain (e.g. the pain of losing $1,000 exceeds the pleasure of gaining $1,000). Some studies suggest that the psychological effect of losses is even twice as powerful as that of gains. This explains the desperate gamblers’ behavior of throwing good money after bad in an attempt to recover their losses, but they usually end up just losing more.

You can manage to break out of the sunk cost trap when making decisions about future resource commitments if you follow these advice:

- Check if your decision making process is suffering any sunk cost bias by asking yourself: “Would I choose to put more resources into that project if no costs were previously incurred, or if its past investments were done for free?”

- Reframe the situation for which the decision is made, by using the frame of gains instead of the frame of losses. This will help you overcome your loss aversion tendency and see the unbiased reality of the situation. Applying this to the above example of the manufacturing facility means to consider the savings of $3 million in future investments rather than getting locked into the $10 million initial investment that was paid in all cases.

- Introduce many intermediate check points to regularly assess the viability of your ongoing projects, so it will be less difficult to kill unsuccessful projects early on (before sunk costs grow very large and loss aversion intensifies).

- Generate more alternatives for moving forward than just the two options: stay on course or kill the project. This will help reveal any hidden assumptions and improve the quality of the decisions made.

Published on October 09, 2013 01:09

No comments have been added yet.