What's The Magic of Wordless Picture Books? by Pippa Goodhart

I love the lyrical text of a picture book such as Malachy’s ‘Dancing Tiger’. I love the pow zap language action of comic strip stories. I love the expressive font usage of particular words in Lauren Child’s ‘That Pesky Rat’. I love the use of pictures as if they were words in Polly Dunbar’s ‘Penguin’. But I also love picture books with no words in them at all. In fact I have an ambition to be the author of a book with no words in it at all. I want to dream-up visual story or stories that will be realised by somebody else – an artist – and I want my picture ideas to be enough without words.

Why? Because pictures on their own leave the audience to do the work of noticing all there is to notice; the job of joining the visual story dots to create the story that is probably more truly their own personal version of the book story than is the case when there are words to guide you.

Many modern reading schemes now begin with simple wordless picture books in order to give children the experience of ‘reading’ a story in a way that all can access, without the skills for decoding text being necessary. They get children into the habit of reading story (as they will with text) from left to right, turning pages from beginning to end.

But, more excitingly than that, wordless books make children use their story imaginations, and gives them the chance to express those stories in their own words. And this isn’t just true for small children, of course. Shaun Tan’s ‘Arrival’ is a wordless picture book that stretches adult imagination in the most brilliant ways.

These books become story creating experiences that hand story power to the audience. Instead of listening to an adult reading out prescribed words, any words (if any are even needed) come from you. That’s exciting, and involves an author/illustrator who dares to trust their audience to handle the story themselves.

These books become story creating experiences that hand story power to the audience. Instead of listening to an adult reading out prescribed words, any words (if any are even needed) come from you. That’s exciting, and involves an author/illustrator who dares to trust their audience to handle the story themselves.Apparently studies have shown that parents ‘reading’ wordless picture books to children use much more sophisticated language than would normally be found in a picture book text. So maybe, ironically, wordless picture books extend children’s vocabulary more than those with words?

What are my favourite wordless picture books?

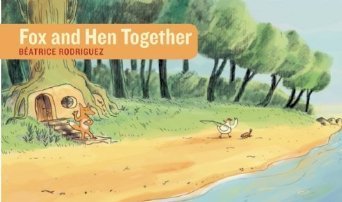

Beatrix Rodriquez wonderful stories about a ‘Fox and Hen’ are exciting, funny, moving and memorable.

Raymond Briggs’ ‘Snowman’, shown in wordless cartoon, has of course become a classic, although many versions of the story now have words added, which seems a shame.

Jeannie Baker’s ‘Home’ is most moving and challenging ‘Home’ and other titles are important books for a wide age range.

Quentin Blake’s ‘Clown’ is another moving tale.

Come to think of it, all these examples are of quite challenging stories. Perhaps wordlessness is a way to cope with what might be uncomfortable if it were to be articulated? What do you think?

Published on October 12, 2013 16:01

No comments have been added yet.