Three Ways to Use Dialogue to NAIL Great Characters

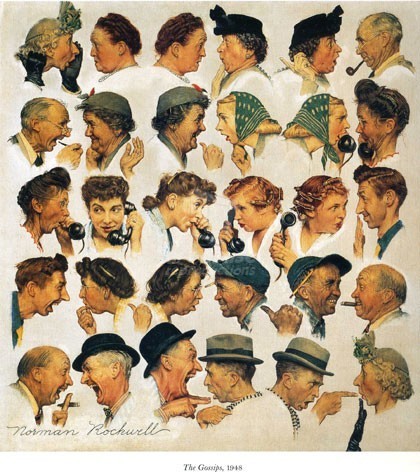

Norman Rockwell understood dialogue!

TEN WAYS TO CREATE UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTERS #5 DIALOGUE

“One psycho with a nuke—that’s all it’s gonna take,” Steve said.

“Armageddon, huh?” Andrew rolled his eyes. “You’re an idiot.”

“Hey, no reason to get nasty,” said Jonathan. “You need to apologize.”

“When pigs fly.”

“Go on now, tell him you’re sorry.”

“Bomb-Making for Dummies—that’s a website!”

“Who appointed you Chicken Little?”

“The sky is falling. And you’re the idiot.”

“Come on, guys, play nice.”

By now, most of you are wondering how this inane conversation got the address of my blog.

But some of you are also saying, “I saw what you did there.”

What I did was drop the attributions. If you didn’t notice, it’s because the dialogue itself made it clear who was speaking. Good dialogue should do that. It should require only the bare minimum he said/she said because the character of the speaker is inherent in every line.

The first thing we need to understand about dialogue is what it isn’t. It isn’t a mirror image of real speech. It’s not dialogue’s job to mimic actual conversation. Dialogue is a literary construct that is “similar to” but not “the same as” real speech.

“Theo, this is … dangerous.”

“Ya think?”

“You won’t like where we’re going.”

“I don’t like where we been! You ever notice how many fat women they is in South Carolina?”

“Theo, I’m serious.”

“And you think I’m not? That woman over there, she got so much flab on her arms she look like a flying squirrel.”

Ty made an unsuccessful attempt to stifle a giggle.

“And them spandex pants. They’s stretched so tight over them thunder thighs, she try to run, her legs gone rub together and start a fire.”

From: The Last Safe Place

Snappy dialogue, but is that the way the people in your life talk? (If it is, invite me to your next party.) Where’s the stammering, the um, the uh, the you-know, the repetition—and totally, like where are all the interruptions and stuff? Can you make up lines like Theo’s on the fly, instead of when you’re lying awake at three in the morning and you nudge Mildred, “I shoulda told that guy…”

Perhaps it’s helpful to think of dialogue as freeze-dried speech—speech with the dull parts taken out. What we say and how we say it reveals volumes about who we are, so if dialogue is concentrated speech, it should give us a concentrated dose of characterization in each sentence. Dialogue should show Loyal Reader in only a line or two what it would take pages of exposition to reveal.

And so I give you the most famous line of dialogue in American film history, ta-da:

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

Those eight words from the 1939 movie adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind tell you in one sentence where Rhett Butler’s journey through the story has finally taken him, from adoring Scarlett to not caring what happens to her.

This snippet of dialogue was voted the number one movie line of all time by the American Film Institute. Likely not for the right reason, though. It should be famous as a stellar example of the single most important role of dialogue in fiction—the sacred function of “show don’t tell.” Every writer should have those three words tattooed in 18 point Helvetica bold on a prominent body part, one he can see when he types. Don’t tell me Mary Anne was angry, show me the end-over-end flight of the Tiffany lamp as she hurls it across the room.

There are, of course, dozens of ways writers can employ the power of dialogue to create unforgettable characters. Absent the space to list and talk about them all, I’m forced to settle for my three personal favorites:

One, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell your character’s mood, state of mind, emotion. Agitated characters stutter, fumble for words, speak in short, staccato sentences, interrupt. Shy characters—and boys in the throes of puberty—speak in one-word, monosyllabic grunts. Scarlett’s frantic, “What shall I do, where shall I go?” is a portrait of uncertainty and fear. Rhett’s responding slam dunk, dialogue-ly speaking, reveals an emotionally wrung-out man unable to feel much of anything anymore.

One, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell your character’s mood, state of mind, emotion. Agitated characters stutter, fumble for words, speak in short, staccato sentences, interrupt. Shy characters—and boys in the throes of puberty—speak in one-word, monosyllabic grunts. Scarlett’s frantic, “What shall I do, where shall I go?” is a portrait of uncertainty and fear. Rhett’s responding slam dunk, dialogue-ly speaking, reveals an emotionally wrung-out man unable to feel much of anything anymore.

Two, you can use dialogue to show-don’t-tell Loyal reader all manner of basic information—that Jerry drinks too much and Stella is afraid of men. But what particularly delights me is the way you can craft a character’s choice of words, the speech patterns themselves to paint vivid pictures.

“You do have a plan, don’t you?” Ron asked.

“A plan, yes,” Masapha replied. “We need all of the money we can lay on our hands.”

“It’s lay our hands on.”

“First, we buy a jeep.”

“Do you know how much a jeep costs?”

“No jeep, no pictures. Can we chase the slave traders running on our feet?”

Ron gestured out the window at the remote little river village. “And where, pray tell, is the nearest dealership?”

Masapha sighed. “There is no dealer ship to the Arab oil fields,” he said. “No river launch or steamer either. It is no water there; it is desert. We need a jeep!” He paused. “It will not be easy to talk me from this.”

Ron didn’t try.

From Sudan

And three, you can craft dialogue to reveal the nuances of your characters’ relationships and show (don’t tell) how they subtly shift and change as they journey together through the pages.

“Bobo, can I ask you a question?”

“That is a question.”

It took me a moment to get it, then I plunged ahead. “Do you know why I’m here?”

“Ever body’s got to be somewhere.”

I put my spoon down carefully and spoke in a quiet voice. “Look, can we just talk? I’m tired of being the straight man in your vaudeville act—The Amazing Bobo and Her Trained Chimp.”

Bobo burst into uproarious laughter. Then I got tickled, too, and we laughed together. When we finally wound down, she was beaming at me.

“Well, you got some powder in your musket after all! I was beginning to wonder.” She reached over and patted my hand. “You ask anything you want and I’ll answer best as I can. But they’s days I don’t know my own self what’s real and what ain’t. Anymore, I can’t swear to nothing.”

From The Memory Closet:

I’ve had those days myself, Bobo, but I’m relatively certain we will be back here next week to talk about unforgettable characters. And I’m completely certain that every one of my writer friends has written dialogue that illustrates the above principles or other equally important ones. Please do share some of it in the comments below so we can all learn from your expertise.

Write on!

9e