'Fire and Forget': A review

Reviewed

by Brian Castner

Best

Defense book reviewer

A

version of this review first appeared in the August issue of Proceedings

of the U.S. Naval Institute.

If you believe the media coverage and

commentary, all of America is still waiting for the great fiction of the wars

in Iraq and Afghanistan. Many of last year's reviews of The Yellow Birds or Fobbit

or Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk

noted the supposed dearth of war novels to that point. In times past, America

waited 11 years for A Farewell to Arms,

16 for Catch-22, and 15 for The Things They Carried. Now our culture

wants to hear who won American Idol

by the end of the episode, and even Anthony Swofford, who knows something about

delayed gratification (his memoir, Jarhead,

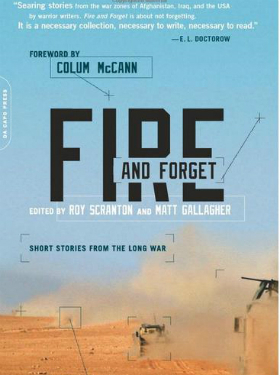

was published 12 years after the first Gulf War), says on the back cover of Fire

and Forget, the new collection of short stories by military veteran

writers, "I've been waiting for this book for a decade."

Is the wait finally over? Yes, according to

Matt Gallagher, one of the collection's editors, who was impatient himself; he

wrote a piece for The Atlantic in

2011 asking when a great novel from the long wars would finally be written.

"Iraq and Afghanistan fiction is in a much

better place than it was when I wrote that article," he told me, before

hedging, "It's just beginning. There's no one dominant story, no one clean

narrative, to emerge from these postmodern, brushfire wars. There are many."

The form of Fire

and Forget follows its function, then: 15 tales with varied perspectives,

and while expected themes of struggle and disillusionment emerge, there is not

a carbon copy to be found here. If you are a fan of literary Paris Review or The New Yorker short stories -- casual tragedy, slow reveals,

ambiguous endings -- you will find familiar hardware in this collection, and

for good reason. These are serious writers, more than half graduates of

master's of fine arts programs, but unlike the traditional college student,

these veterans bring a life experience to the form that is substantial and

heart-breaking.

Perhaps fittingly, considering the

post-traumatic stress disorder newspaper headlines, there are more stories here

about the challenges of return than the horrors of war, more whiskey bottles

flying than bullets. In a number of stories about surreal post-war moments,

animals act as symbolic stand-ins for innocence, and thus are mercilessly shot,

squashed, and buried. For me, the stories of in-country combat were a

comparative relief from the grinding tales of heartache at home. At least we

know how the firefight will end; we have no such certainty about those still

laboring to reintegrate.

The winner for sheer visceral impact is Phil

Klay, whose story of returning is so spot-on I wonder if he wrote it while

still on the plane ride home. He gets everything pitch perfect, and not just

the major points, such as wanting to go back to war right away, literally hours

after landing. No, it was the small truths that returned me to my own

homecoming: the unfamiliar softness of a wife's embrace after months of hard

Humvees, the pleasant satisfaction of the first hangover. Klay remembers the

details so the rest of us don't have to.

David Abrams, the author of Fobbit, tells the brutal story of a unit

remembering fellow soldiers lost in combat, not with nostalgia but rather

obscenity-laced efficiency. "This short story is more typical of what I

normally write," Abrams told me. "It has more dramatic punch than . . . comedy veneer."

Siobhan Fallon's excellent story from the

perspective of an Army wife is a breath of fresh air, one that comes early in

the anthology and that honestly I could have used a little later. The veteran

experience can feel insulated and claustrophobic, and Fallon's incongruence

with the other pieces -- the only one not from the perspective of the solider

or veteran (although Gallagher's contribution is half and half) -- begs the

question, where is a piece about an Afghan family? An Iraqi interpreter? A new

refugee? Instead, the Iraqis and Afghans in Fire

and Forget are always "hajjis" or, in the words of contributor Ted Janis's

protagonist, "[expletive] traitors."

Why is this? "I think veterans are still stuck

in their own head," said Abrams. "And I think we Americans, to paint with a

very broad brush, lead very insular lives. We don't naturally think about

foreign policy. But for the purposes of this anthology, it's fine. Each of

these works of art stand on their own."

True, and they do so well, but even the story

from Andrew Slater, now a teacher of English at the American University in

Erbil in northern Iraq, is about a U.S. soldier struggling with traumatic brain

injury at home. Would he not have been the writer to bridge the gap? His story,

though, is so troubling and thought-provoking that I wouldn't trade it and

that's the point, isn't it? After 12 years of war, we're just starting to

understand what happened to our own soldiers. Perhaps in time we'll reach

across the gulf to those we were fighting -- with and against.

Brian

Castner is a former U.S. Air Force captain and explosive ordnance disposal

officer. He is the author of The

Long Walk: A Story of War and the Life That Follows (Doubleday, 2012). This review is reproduced here with the permission of its author.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers