The Cornwallis Connection

Charles Cornwallis, First Marquis of Cornwallis (1738 – 1805) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Last week, I was walking around downtown Charlotte, N.C.. Standing in front of the Bank of America tower, I noticed a marker indicating I was at the site of the Battle of Charlotte, which occurred on Sept. 26, 1780.

Back then, it was the site of the Mecklenburg County Courthouse, at the intersection of the town’s two main roads. An advance guard of British troops rode into town and found themselves confronted by a well-armed Patriot force. The Patriots fought off the guard, then withdrew as the far larger main army of British General Charles Cornwallis advanced on the city. Cornwallis’ attempts to occupy Charlotte, though, never really succeeded, thanks to persistent Patriot resistance and he eventually withdrew to South Carolina.

As I continued my walk around downtown Charlotte, my thoughts drifted from the battle to Cornwallis to an old NASA missile retriever docked near Yorktown, Va. — a roundabout connection between the British general and my father, and story that I didn’t include in The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.

In the summer of 1975, I was involved in one of the great boyhood rites of passage. My father was teaching me to use a lawn mower. We were in our back yard in Pennsylvania, and I’d made my first pass under my father’s supervision when my mother came out the house and told my dad he had a phone call. We turned the mower off, and I waited, anxious to get back to the tutorial. (My interest was economic. Lawn mowing was a chore my parents paid for, and with my brother heading to college, I was eager to step into the gig.)

When he returned, though, my father had another idea: how would I like to come with him and spend the weekend on a boat in Virginia?

Our destination was Gloucester Point, at the mouth of the York River. Working with the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences, members of the fledgling Institute of Nautical Archaeology were consulting on the excavation of Revolutionary ships from the Battle of Yorktown, which essentially ended the Revolutionary War.

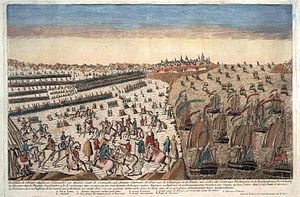

Overview of the capitulation of the British army at Yorktown, with the blockade of the French squadron. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

About a year after the Battle of Charlotte, on Oct. 19, 1781, Cornwallis had moved his fleet to the York River and found himself hemmed in by land and sea and surrendered to George Washington. Before the surrender, Cornwallis, who still had about 60 ships at his disposal, ordered some of them scuttled at the mouth of the river in a desperate attempt to stave off the approaching French fleet.

We spent the weekend on an old boat that NASA had used to retrieve missiles after test flights. The space agency donated it to the school, which was using it as a dive boat. For a 9-year-old boy, it proved an exciting weekend playground.

Several of the scuttled ships were found as a result of those meetings and five years later, a team lead by archaeologist John Broadwater found the HMS Charon, Cornwallis’ flagship. The Charon caught fire and sank in the York River in the final days of the war. My father directed the INA field school that helped excavate the Charon in the summer of 1980. It was the only field project he ever directed. He didn’t enjoy the administrative side of archaeological projects, but he later told his colleague, George Bass, that he wanted to do it to prove to himself that he could.

Cannons and other artifacts from the Charon and other ships from the “sunken fleet” excavated in the York River are on display in Yorktown, and the river continues to yield new discoveries.