It’s a small small world…

I AM BACK in Japan. This time just for a week, but it’s action packed. Six lectures in all, but the final one on Tuesday is the one that matters most. It’s at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, in front of an audience of about 600, where I get to give my take on the future of planet, life and people over the next 1,000 years in the light of a warming climate and the relentless rise in human populations.

Hmmm… It’s something I have thought about quite a lot over the last few years. Big history helps – at least I hope so – since hindsight and foresight are remarkably similar. Looking into the future means just turning your head the other way. It is no more or less certain than the past, actually. Big themes, interconnected disciplines, and generalisations based on rational foundations are the best guides, and I think the chances of getting it ‘right’ are about the same. In the end history and futurology are ultimately matters of opinion and interpretation made more or less convincing by argument based on selected evidence.

Perhaps it is our ability to evaluate the past or speculate on the future that especially distinguishes human brains. That’s where I think we differ from dogs. Flossie, our westie, is infinitely more present or conscious in the here and now than I am, or ever will be. Her sniffing, her focus on the moment are qualities that matter most in the wild, in the state of nature, where survival is a matter of the utmost care.

Flossie, our westie, is infinitely more present or conscious in the here and now than I am, or ever will be

Imagine a tiger ready to pounce on its prey – just one careless move, a snapped twig, is all that stands between a hearty meal and frustrated hunger. Nothing like lunch (or the lack of it) can focus the mind better on being aware in the present. And the prospect of being someone else’s lunch is no less mind sharpening….

But we humans are different. Civilisation has numbed our sense of the here and now. I really think we are, in this way, so much duller in the heads than our hunter-gathering ancestors. Being safe from instant predation by wild attacks masks us from the need to worry about being eaten in an instant if we tread carelessly on that twig in a wood. As a result our swollen cerebellum turns itself on the past (and the future) in its bid to avoid being bored. Therefore, we gain hindsight and foresight – from which come a sense of time, history and destiny. Perhaps that makes us unique amongst living beings?

If you happened to be listening to the PM programme on Radio 4 last week you may have heard an interview featuring Edmund Burke – the great TV presenter of the classic 1970s history series Connections. Quite why he popped up again last week I can’t quite recall, but his habit of interlinking knowledge is something I find appealing. He was being interviewed about the future – the same topic I am readying myself to address next week: My ears instantly picked up – as if a twig snapped.

Burke declined to give his view on the next 10 – 20 years – it’s simply too close to the present to be able to predict. But reach out 40 years or so and the horizon begins to get a little clearer. I take his point.

His verdict was astonishing. There was none of that climate change, end of the world, rising sea levels, bird flu, great famine crisis kind of stuff. In 40 years time technology will have come, like Polish King Jan Sobieski III, in just the nick of time to rescue modern civilisation from drowning in its own excrement. By then science will have invented something so revolutionary that it will, at a stroke, destroy capitalism and save the planet at one and the same time.

Look on ye mighty and despair at the nanofactory!

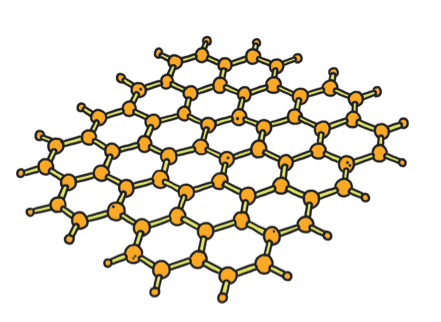

It’s a machine – based around today’s quantum tunnelling microscope technology – that will be able to manipulate matter at the atomic level and arrange atoms of a given element or compound into an exact copy of anything – anything – you want to consume, own or just marvel at. It’s a kind of super-souped up version of today’s 3D printers.

Food is almost entirely made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Just feed these common elements into the nanofactory and it will build – atom by atom – according to a scanned image or downloaded design – anything you want to eat. A cucumber – a steak – a glass of chateauneuf du pape. Perhaps you could even make your lunch out of excrement – that’s got most of the ingredients…

The idea isn’t so completely bonkers and 40 years is a long way out, given today’s rate of technology innovation. Much of today’s food is synthetic already – from vanillin to corn flakes – thanks to the ubiquitous corn fructose syrup.

But the nanofactory will be able make anything all in the comfort of your own kitchen – possessions, computers, clothes, toys, furniture….

‘Just imagine!’ marvelled Burke.

Once the consumer has such technology there will be no market (except I guess for the nanofactories themselves) because there will be no need to buy stuff – you just make everything on demand. There will be no hunger, no inequality, no resource crisis. Everything will be recycled, remanufactured from the bottom up to make whatever happens to take our fancy. Today’s miseries and tomorrow’s forebodings gone in a flash of genius!

Once the consumer has such technology there will be no market because there will be no need to buy stuff

But as I switched off the car engine and the radio fell quiet, a feeling of inevitability soon returned – despite Burke’s irrepressible optimism. The second law of thermodynamics always spoils the party! How much energy would it take to make all these things? And where is all the energy going to come from to make, let alone power, 10 billion nanofactories all spewing out commodities to satisfy our never ending fetishes…?

All of which brings me back to Japan, now without nuclear power and facing its biggest economic challenge for a generation thanks to the ongoing disaster at Fukushima.

I shan’t be mentioning Mr Burke at my talk on Tuesday next week – although if any great nation can make this nanomiracle into a reality, I guess it will be the Japanese. Still, I find the idea intriguing – perhaps it is a possible solution to the world’s ills. Whatever, it would make the basis of a cracking novel if only I had the skills of an H.G. Wells!