A whale of a time in Tonga

by Christine Kling

What I remember most about the kingdom of Tonga is churches, fruit bats and whales.

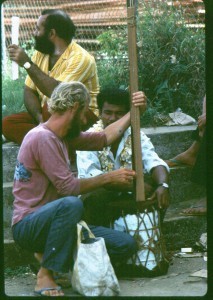

When we visited Neiafu in the Vava’u group it looked like there were almost more churches than houses in the village.  And on Sunday morning, the church bells were ringing non-stop and you could hear the music and the singing in stereo out in the anchorage. They loved their music and they crafted instruments out of whatever they had at hand. In the photo at left, Jim is admiring a Tongan version of the washtub fiddle. But what we found most remarkable was that the constitution in Tonga stated that Sunday was their Sabbath and it was required by law that no business of any sort could transpire on that day. In addition, it was illegal to engage in any game, sport, dancing or fishing. After having narrowly escaped jail for gun running in French Polynesia, we weren’t about to risk jail by snorkeling on Sunday.

And on Sunday morning, the church bells were ringing non-stop and you could hear the music and the singing in stereo out in the anchorage. They loved their music and they crafted instruments out of whatever they had at hand. In the photo at left, Jim is admiring a Tongan version of the washtub fiddle. But what we found most remarkable was that the constitution in Tonga stated that Sunday was their Sabbath and it was required by law that no business of any sort could transpire on that day. In addition, it was illegal to engage in any game, sport, dancing or fishing. After having narrowly escaped jail for gun running in French Polynesia, we weren’t about to risk jail by snorkeling on Sunday.

Another thing Tonga was known for was the fruit bats. We putt-putted in our dinghy out to one of the uninhabited little islands around Neiafu and found a whole colony hanging in the trees. They were creepy-looking, but fascinating creatures. Jim stood up in the dinghy and hollered and waved trying to get them to take flight. The ones we spotted weren’t nearly as lively as the ones in this video. Ours looked more like they were sound asleep.

It was our encounter with the whale — or I guess I should say the whalers — that made the strongest impression on me. When we visited Tonga in 1975, whaling was still legal and a fairly common practice. The original Polynesian people did not include whaling in their culture, but the practice was brought to the islands by Captain Cook and the New England whalers who followed.

So it was that when we were in Vava’u, an open wooden boat about 25 feet long took off one day with 6-8 men aboard. We heard in the village that they were going whaling. People said they often went out whaling, but they rarely caught a whale. Later that afternoon, however, we looked out from the anchorage, and we noticed the boat traveling quite fast between the little islands that you can see in the photo at the top of this page. The outboard wasn’t running and they weren’t rowing. They had harpooned a whale and the boat was being towed around as the whale swam and slowly tired itself out. This took several hours.

Close to dusk, the boat came motoring slowly into the anchorage. Lashed beneath the 25-foot boat was the body of a 40-foot whale. They ran the boat as fast as they could get it to move straight at the beach until the whale hit bottom. Then they lashed a rope to the whale’s fins and body and all the men from the village came to the beach and heaved on the line like a big tug-o-war pull.

By the time the whale was securely beached, part of the head and a bit of the back was visible, but the rest of the body was still under water. From the moment the whalers first returned, canoes and boats had started arriving from the outer islands. Word had traveled on the coconut telegraph alerting the people on the surrounding islands that there was soon to be whale meat for sale. The men stripped to the waist, took their machetes, and waded into the water. They began to hack at the body of the whale. Since whales are red-blooded mammals, the dark red stain began to spread until all the water in the anchorage looked almost black in the darkness.

A small wooden boat floated just off the submerged body. A pressurized lantern hung from a cross trees in the boat. It lit the waters all around the body of the whale. Heads bobbed in the water as the swimmers took deep breaths then dove to carve away at the carcass. When the butchers surfaced with their hunks of meat, they swam over and threw the meat into the bottom of the boat. A large Tongan woman sat in the center with her old fashioned iron scale and a set of weights. The customers pulled their boats alongside and gave her their orders. She’d hack the requested size chunk of meat off the many slabs in the bottom of her boat and throw it on the pan on one side of her scale. Then she’d add the weights to the other side. A man sitting next to her collected the money as she wrapped the meat in paper. That boat would pull away and a new customer would row into the lamp light and place his order.

From time to time all the men would exit the water and line up again on the beach and take hold of the rope. Chanting, they heaved in unison and pulled more of the body onto the beach exposing more flesh. Then they returned to the water and began diving and hacking away in the blood red bay.

Jim and I got in our dinghy and rowed over to watch the scene. I couldn’t believe that the butchers in the bloody water were not afraid of sharks. But there didn’t seem to be any sharks bothering them. I have vivid memories of feeling both excited and frightened as Jim rowed us around the whale. Very few of those people spoke English and there was something so brutal and primal about the knife-wielding divers and the excited, almost blood-thirsty buzz of the crowds in the boats. For this 21-year-old California girl it was a real “you’re not in Kansas anymore” moment.

Eventually, we pulled alongside the drive-thru whale meat store and bought ourselves a pound of meat. It looked very much like beef, except that the fibers or strings were bigger and there was absolutely no fat marbled in the meat.

Back on the boat we decided to cook the whale meat in the pressure cooker with some onions, carrots and potatoes. It had a dense, almost chalky taste and though we tried to stew it, it was still tough. We couldn’t eat it. I would like to say that was because of some higher moral sense, but in those days I was young, and I wanted to try everything. The animal was already dead, and I liked the adventure of it – to try whale meat. But I couldn’t stomach it. I cannot understand why the Japanese are so intent on keeping meat from marine mammals in their diet.

The next morning the bones were about all that was left on the beach.

Three years after our visit, in 1978, the Tongan King issued a royal decree banning whaling in the kingdom, and today Tonga is well known for its tourist industry that specializes in whale watching expeditions. Over 100,000 people each year get to see the humpback whales when they leave Antarctica to breed in the warm waters of the South Pacific. Thankfully, the people of Tonga learned that live whales are far more valuable to them than dead ones.

Fair winds!

Christine

Share on Facebook