Banned Books Month: Guest Post from Chris Willrich: In Defense of A WRINKLE IN TIME

It was second grade, and Mrs. Origines had herded me, a wayward sheep, into a classroom alcove. In her kindly but implacable voice she said I must stop disrupting class and pay attention, and that I wouldn’t be able to leave until I agreed.

This eventually gets around to banned books. Trust me.

Looking back, it seems I was a boy with focus issues. In my own mind it wasn’t that I wanted to ignore the teacher, it was that every room I entered was full of charming, distracting objects. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to study, it was that my imagination was always tugging me into exciting places with spaceships and swordfights.

Mrs. Origines had me figured out, though. I couldn’t disengage from her. She was not a big person, but with her arms folded and her eyes fixed on me she might as well have been a linebacker. I realized I couldn’t wiggle away.

I nodded, but she didn’t let me go until I’d looked her in the eye and given her a spoken “Yes.”

The cast of Star Trek: The Original Series.

I doubt I was a model student after that, but with the fear of Mrs. Origines in me, I did pay more attention. And honestly I don’t think it was just fear, but a dash of shame, a sense I’d been slow to act my age. I wonder if my teacher felt a little sorry for me, or if it was just part of her program of civilizing this barbarian child, but one recess she said, out of the blue, “You like Star Trek, don’t you?”

Of course it wasn’t a secret that I liked Star Trek. In those days it was just a canceled three-season Sixties show living on in re-runs; but a lot of kids liked it. It had spaceships and fighting, after all. But for an adult to have actually noticed was unnerving, as if someone had probed your mind with telepathy. (You could see that on Star Trek too.)

I couldn’t quite put telepathy past Mrs. Origines.

I managed to say, “Yes.” That seemed safest.

“Do you want to know how the warp drive works?” she asked.

If I was surprised that an adult wanted to talk Star Trek, imagine my shock that one would ask me about warp drive.

“Do you?” she said.

I think I was nearly speechless, but somehow managed to convey my interest. Her manner was so serious that I could almost believe that here, in Olympia, Washington, in the second grade, here was someone — a time traveler perhaps, a secret inventor, an extraterrestrial in disguise — who really did know how to send a ship moving faster than the speed of light.

Interior Art from A WRINKLE IN TIME.

The book she brought me did not look entirely promising however. It looked like a kids’ book, not a technical manual from the 23rd Century. She opened it to a page with a line illustration of an ant walking on the edge of a skirt. This did not seem very starship-like.

The ant on the skirt, Mrs. Origines explained with the aid of the pictures, could be like a starship in space. To get to a more remote area of space, it would be convenient to be able to fold space, just as the pictures showed the cloth being folded, allowing the ant to walk a few steps to a distant spot.

Fold. As in warp.

I still didn’t quite get it, though.

“To understand,” I think she said, “you have to read everything up to that part. Maybe you’ll want to read past that. But I just want you to agree to read up to the part with the ant.”

Of course I agreed. This was Mrs. Origines. And I had to admit I was intrigued.

Many, many books later I would become a children’s librarian, a field that terms what Mrs. Origines did with that skittish second-grader booktalking. This was surely one of the oddest booktalks there ever was. But it was effective, because it introduced me to Madeleine L’Engel’s A WRINKLE IN TIME.

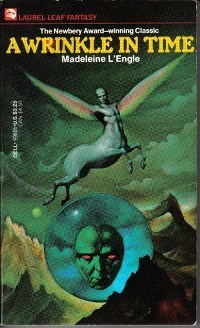

Bantam Books, Mass Market Edition, October 1988.

Now, my second-grade self would like to inform you that the method of space travel in that book — to tesser, as L’Engel, with her wonderful gift for coinages, called it — isn’t much like warp drive after all, since warp drive is obviously much slower and requires huge engines, while L’Engel’s charming aliens Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which can travel much more swiftly with just the power of their minds. Still, the basic point was sound, and why split hairs, as my teacher’s ploy took me across the galaxy with Meg Murry and Charles Wallace and Calvin O’Keefe. It took me still farther, to L’Engel’s A WIND IN THE DOOR and A SWIFTLY TILTING PLANET.

In L’Engel’s books I learned a little about totalitarianism, mitochondria, and the danger of nuclear war. I imagined myself kything, being mentally present with beings in distant places, microscopic realms, or other times, and I’ve never stop wishing I could really do it. To a churchgoing kid it was exciting to see religious themes explored, with a light touch, on a cosmic canvas to rival anything in Star Trek (a feeling I’d later get from reading writers as disparate as C.S. Lewis, Philip Pullman, Arthur C. Clarke, Olaf Stapledon, and Gene Wolfe.) I also intuited some other themes, about bravery that doesn’t involve violence, about how we humans are in this together in an often hostile universe, and, eventually, a mature view of romantic love that had little to do with its popular portrayals, then or now.

Naturally as a librarian I often recommended A WRINKLE IN TIME. I didn’t get as many takers as I wished, but, then, there are many wonderful books out there. And a few times my booktalking, though lacking the punch of my second-grade teacher’s, managed to work.

Also naturally, I was startled the first time I discovered L’Engel’s classic has been frequently challenged by people hoping to keep it under wraps. Critic Anita Silvey writes, “Censors have decried the didactic qualities of the text or the overt Christianity; others have objected to Mrs. Which and her resemblance to a witch.” Sometimes it seems the book can’t win, condemned for being too religious or not religious enough.

Trying to suppress a work is like the mirror image of booktalking. Instead of talking a book onto a reader’s nightstand, we try to talk it out of existence. Yet it so often seems a self-defeating gesture. Trying to remove a book stirs up discussion, and builds up interest. And even the rationales so often seem misdirected. George Orwell’s classic anti-totalitarian novel 1984 has been condemned on the grounds it’s somehow pro-communist. Similarly, Lois Lowry’s THE GIVER has been challenged for presenting grim details about a dystopian future — the whole point of a cautionary tale!

Little, Brown and Company, Mass Market Edition, May 1991.

There’s also the peculiar way in which swearing, sex, and substance abuse sometimes seem to trump every other aspect of a book. One of my college professors remarked it baffled him why an essentially “sweet and innocent” book like CATCHER IN THE RYE attracted so much fury, while a book as savage in its outlook as WUTHERING HEIGHTS remained serenely on high school reading lists. J.R.R. Tolkien’s work has been challenged because we see wizards and Hobbits smoking tobacco. Author Cory Doctorow has said it surprises him how his near-future thriller LITTLE BROTHER, which depicts teenage hackers challenging the U.S. national-security apparatus, catches flak for mentioning sex, drugs, and alcohol, while its government-defying message is shrugged off.

Ultimately, attempts to ban books seem to have more to do with the obsessions of the would-be censors than with the books themselves. Some people appear to fear that to name a thing, or to describe it, is also to endorse it. Some believe that it’s wise to shield children, including teenagers, from even watered-down discussion of life’s tougher realities. Many seem trapped in a fearful, even medieval, worldview where saying a few words in Latin, like the wizards in the HARRY POTTER series, can invoke evil forces. And some have such a narrow, controlling take on their own religion that they condemn co-religionist authors (Tolkien, Lewis, and L’Engel being great examples) who bring aspects of their faith into their imaginative visions.

Pyr, September 2013.

As a children’s librarian I never personally experienced a book challenge, though I did hear now and then frustrations that our library would carry or recommend certain materials. Part of the job, as I saw it, was to have empathy, and often I could intuit where people were coming from. Sometimes it’s a perilously short jump from thinking, “I would rather my child not read this” to “I would rather no child read this.” As a father of two, I’m often struck by how different two families, and two individual children, can be; and yet sometimes I’ve felt the temptation to think my own experience is universal. As a fiction writer, I try to get into the heads of characters very different from myself, to kythe, so to speak. Thus, I can see at least some book challenges as stemming from misplaced protectiveness.

Yet sympathy has its limits. If A WRINKLE IN TIME had never come my way, it’s possible things would have been all right. But it’s also just possible I’d have become one of those boys who misses out on the pleasures of lifelong reading, a hole in my universe that even the crew of the starship Enterprise couldn’t fix.

So during this celebration of the freedom to read, with its promise that no would-be censor ever gets to disrupt the whole “class” as it were, I would like to share the wish that every book challenge be met with a Mrs. Origines standing beside the bookshelves — benevolent, empathetic…and utterly implacable.

Sources consulted:

Banned and Challenged Books web resource, American Library Association, retrieved August 2, 2013. http://www.ala.org/advocacy/banned

Banned Books Awareness web site, maintained by R. Wolf Baldassarro, retrieved August 2, 2013. http://bannedbooks.world.edu/about/

Doctorow, Cory, interview. Conducted by Anne Strainchamps. To the Best of Our Knowledge (radio program), March 13, 2011. Audio file available at

http://ttbook.org/book/cory-doctorow-little-brother

Silvey, Anita, 100 Best Books for Children. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

[image error]

Chris Willrich.

Chris Willrich, a former children’s librarian, is the author of THE SCROLL YEARS (Pyr 2013), a fantasy novel that does its share of bending space and time.