The Ordinary Weather (Part III)

I’ll be periodically posting pieces of the following. If you haven’t picked up a copy of David Brazil’s The Ordinary, it’s available here.

- - -

9-2

From “Election”: “Love is the wound which makes the hinge from which pours time in purer form.”

9-3

Conversation w/Julia while walking around North Loop two nights ago: per David’s “Kairos,” and per actual weather—and probably per Spicer—a process shaped on the writing event as an interval of time. So drafting/writing that takes shape and dissipates—not contra revision but against the push to arrive at some final form (a poem shaped as such, a book, etc., recognizable as such in its shape). Against the willed shape or gesture. Writing as an interval that punctuates thought, language, speech, or art as a disaster punctuates a life. (So writing as punctuating a life.)

Also, yesterday, listening to Grenier/Ratcliffe talks and feeling less in common with the daily practice of the latter now, after my having set out on a slow version (monthly) last year. Or at least aware of a new proclivity in me toward some more dramatic interval than dailiness, as an instigation to work. Or, in David’s formulation, “Love” as “wound” or cleft that opens onto “time in purer form.” A process shaped on that hinge, that opening.

9-4

Inasmuch as first responders annotate a disaster site—drafting from the unoccupied to the expired or still hanging on—they literally offer the first response.

From what I could gather, there wasn’t much to their shorthand—just a square with an X in it when a structure had been cleared (i.e. no bodies inside) and elsewhere, the count of those who’d perished on site (“1 D.O.S.”). All of which spray painted large on cars and sides of houses—as visible a gloss as possible on any structure likely to have been used as shelter during the storm.

Tracing this weird, almost surgical itinerary, the first responders’ marginalia are inextricable to me now from David’s strike-through’s—though I’d pry them apart if I could, and I think I probably should. The one above I attempted (in my panic) to remove with sandpaper, and now it’s permanently installed on the window of my dad’s (now my) Silverado.

9-5

Not after an open form, but a form opening, forms of opening. That hinge.

9-10

A book confronting the problem of “If I’ll tell what I found there I8ll have to tell that other thing as well” (LXXXV).

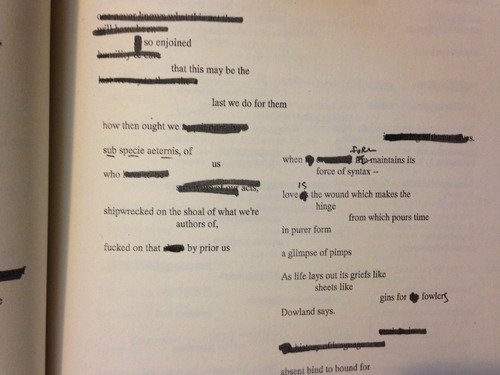

In “Descort,” one of the previously self-published Xeroxed chapbooks featured in The Ordinary, debris itself almost achieves the status of a kind of nonce form. Each page features a Xerox of typed text with strike-through and a square typed scrap:

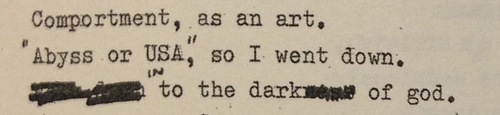

This page I can’t quite shake. There’s something of guilt or worry in the concern about telling “that other thing,” but I also recognize it as naming an anxiety about cohesive telling, so that “what I found” and “that other thing” would stand for something like debris and the impossibility of organizing the report about the debris. Or “matter and its conditions for being otherwise” (Elizabeth Grosz). Or maybe form and comportment. In Susan Gevirtz’s “Belief’s Afterimage: The Recent Work of Barbara Guest,” she offers “comportment” as a useful alternative to “poetics”:

A comportment toward language, the mystery. A practice of approach, that is, of writing “which expresses ‘yes’ and at the same time ‘no,’ [named] by an old word, releasement toward things.” The release of meaning to its own life beyond what is meant “Moves outside the text into the dark under text…” (Coming Events 110; quoting Heidegger and Guest, respectively)

In particular, the idea that “the release of meaning to its own life” is a downward momentum—Guest’s “dark under text”—is something that resonates with “comportment” in David’s poem, which itself is “an art”:

Walking the path from my grandmother’s house to the area where the house landed, I often felt myself becoming somehow heavier. Not just my steps, but my whole person sagged under whatever weight, dug in like my center of gravity were a foot below the surface of the ground. The path went from the evacuated footprint of house and shed to their strewn remnants. Someone had pointed out for my brother the spot where my family landed, which was where I’d inevitably wind up. (Under the weight of meaning released to its own life? Gone under, with meaning?)

In the wake of what happened to my family, we’ve all (at some point) attempted to thread a narrative through the events that would be capable of recovering sense in what happened. In a way, it’s a kind of lifeboat gesture—not that there’s a way out, but (smaller goal) that there might, in the right narrative, be a way to stay afloat.

One story goes that my dad saved my mother’s life by telling her to hold onto the doorframe, which she did. This one, by the time it got to the reporters, became the overwrought lead-in to the article on my dad and grandma in the local paper: “Tommy Joe Martin would probably be alive today if he had been a more self-centered person.” (Fending for himself most certainly wouldn’t have saved him from a tornado touching down on the house he was in.)

And there were the efforts to pin down a timeline that would show the storm hitting before the emergency siren went off. It’s literally across the street from my parents’ house, and the neighbors, who helped us look for both the contents of the house and someone to blame for their dispersal, say it went off too late.

Such efforts at sense attempt to tamp down questions that seem to insist on darker meanings: like the question, for my mother, of whether my father knew, in the last moments before they were thrown, what was about to happen—whether it was resignation in him that made him just sit down on my grandmother’s bed—and what she’s supposed to do with that image.

Or for those of us who could easily have been at the houses that night, the question of what that would have mattered. Julia and I, along with two of my mother’s siblings, had visited days before for Mother’s Day, and any of us could have stayed on until Wednesday (we’d all considered it, if memory serves). My dad’s sister and her husband had planned to come visit my parents on the night of the storm, but stayed home once they saw the weather forecast. Confronting the question of what might have been different is something I think we’ve all wrestled with, despite the likelihood that more people would have meant little more than more people gone.

The notion of “a releasement toward things” or “the release of meaning to its own life beyond what is meant”—of comportment, as portable to the context of grief, as a potential an aid in finding a relation to meaning in the aftermath—I want to think that I can practice this. That I can work at “releasement toward.” If I say that I will work at it, I’m probably also saying I’ll fail at the work. Or if it’s about releasing control of meaning, maybe comportment is less a strategy than a means of surrender.

—-

Read Part I of this piece here.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers