Beyond the Horizon – short story, part 1

Everett Ross, the protagonist in my World War I novel Once A Knight, is an ex-Texas Ranger (lawman not ballplayer) who has joine d the Royal Flying Corps before America has entered the war. The story of how he exchanged his horse and six-gun for an open cockpit Nieuport and Lewis machine gun is hinted at through the novel’s back story but never spelled out in detail.

d the Royal Flying Corps before America has entered the war. The story of how he exchanged his horse and six-gun for an open cockpit Nieuport and Lewis machine gun is hinted at through the novel’s back story but never spelled out in detail.

I’m working on a series of short stories to explain the events that led Ross to such a major change of lifestyle and vocation. Or is it such a major change?

Here’s the first half of one of those short stories. I’ll post the rest of the story tomorrow.

Beyond the Horizon

(August 1910)

by Walt Shiel

I swung down out of the saddle. Dust swirled around my boots as they hit the ground. While scanning the horizon to the west and north, I took off my old Stetson and mopped the band with my kerchief. No sign of Dan Hutchins as far as I could see.

I hooked the Stetson over the saddle horn and knelt down to examine the horse tracks I’d spotted. With the hard clay heat-baked, finding tracks at all had been a bit of a surprise. The horse’s hooves had dug in pretty good, though, apparently trotting. The horse that made them was unshod. I gently brushed the loose dirt from a right-front hoof print.

Yup. There it was, clear as could be—that wide, distinctive split in the hoof wall. The same marked hoof print I’d been following for the past three days. And the split was getting worse. If Hutchins’s horse wasn’t already lame, it soon would be.

I pushed my hat back on my head and lifted one of the canteens off the horn. I took a satisfying drink and wondered about Hutchins. As far as I’d been able to determine, he hadn’t gotten any water when he stole the horse and hadn’t stopped at the last windmill-fed water tank many miles back. I’d filled up all four of my own canteens and the leather water bag for Charcoal, and then let him drink from the tank.

Hutchins, riding hard and long in the late August heat without little rest or water, must be worn out by now. I suspected his horse might give out before he did.

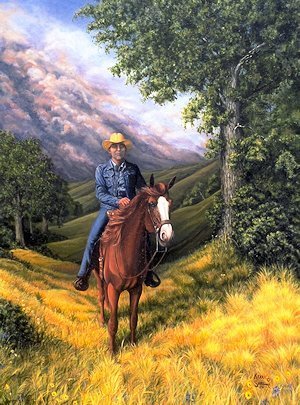

On Horseback. Oil on canvas original. Copyright ©1990 Carolyn M. Shiel. All Rights Reserved.

I poured some water from the bag into my Stetson and let Charcoal suck it up. He got most of it before it leaked through. I put the wet hat back on my head, the cooling dampness felt damn good, and swung back into the saddle. Resigning myself to a long, unpleasant ride through this god-awful country in the worst heat and drought we’d had in west Texas in many years, I clicked softly. “Let’s go, Charc.”

Charcoal, a 16-hand Tennessee Walker, set out at his easy, running walk, a gait he could keep up for a long time thanks to careful breeding by those plantation owners decades past. I was in no real hurry since I figured Hutchins was no more than two hours ahead and would soon be on foot. I just kept Charc headed generally northwest and kept watching the ground ahead of us, hoping to pick up some more tracks.

Something just above the northern horizon caught my attention out of the corner of my eye. I jerked my head around and pulled Charc to a stop, expecting to spot a circling hawk or buzzard. I could never help but stop and watch them. But whatever it was wasn’t circling. It seemed to be making beeline for me and Charc.

As it steadily came closer, it grew and grew until finally I could make out a double pair of wings. One of those newfangled flying machines. It had to be. I’d heard tell of them and even seen a faded photo of one from an old newspaper somebody’d drug in to Texas Rangers headquarters in Austin a while back.

Soon I was able to make out the head of the guy driving the machine. He wore some kind of goggles and leather helmet.

And it did make a racket. A heart-stopping, whirring, roaring, thundering noise that got louder and louder as it approached us and passed right over my head. I craned my head back to get a better look. It was mostly just tubes and wires and some material stretched tight over the wings, showing off the structure underneath like a half-starved man’s skin showed off his ribcage. And a spinning contraption out front that looked as though it might have blades like a windmill.

Charcoal snorted, shied a bit, and pawed. I patted his neck to calm him down.

The contraption couldn’t have been more than a hundred feet above us. The guy leaned the thing over to the left and circled clockwise around us. A long, white scarf flapped in the wind his speed had made. There sure was no wind down there on the ground where I was.

He waved, so I waved back. Friendly cuss, I thought with a shrug.

He shouted something at me, but I couldn’t figure it out what with the commotion of his engine. He shouted again, and I could almost make out his words. But not quite.

I shook my head and cupped my hands behind my ears. Charcoal set back a bit on his haunches, getting ready to bolt, and I had to snatch up the reins and stroke his neck to settle him down. Although he’d been around plenty of locomotives, none of them had ever flown over his head.

The guy in the flying machine leaned over the side and slowed his motor so it quieted down a bit. He cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted, “Which way to Abilene?”

Abilene is where I’d been day before yesterday, and it sure as hell wasn’t south the way he had been headed. Rather than try to shout back at him, I twisted around in the saddle and pointed to the southwest.

The fellow nodded, waved again, and made the machine rock side to side a couple of times, then just turned west southwest and flew off. I turned Charc around, and we watched that machine get smaller and smaller until we couldn’t see it anymore.

I bet I sat there in the saddle without moving for five full minutes. Flabbergasted, that’s what I was. It looked as if that flying fellow could cover in an hour or so about the same distance Charc and I had taken all morning to cover. And I was sure he was a lot cooler up there with that wind blowing in his face than I was down on the windless, sun-baked plains.

Slowly, reluctantly, I turned Charc back to the northwest and clicked him into his running walk again. He snorted a couple of times before settling down. Although I kept watching for Hutchins’s tracks, my mind was somewhere else. I couldn’t stop wondering what it would take to trade places with that flying fellow. What would it be like to soar up there with the hawks?

We rode on through the heat and dust. I spotted enough tracks from Hutchins’s horse to confirm we were still closing in on them. In mid-afternoon, we came across Hutchins’s saddle tossed in a low spot behind a some sagebrush. Later, as the sun dipped low to the west horizon, we came across the aging gelding Hutchins had stolen, limping slowly towards Abilene, back where Hutchins had stolen him.

I swung down and looped a rope around his neck to hold him still. I lifted his right front foot and examined the crack. The crack had widened and stretched farther upwards. I pulled my hoof rasp from my saddle bag and rasped a flat spot across the crack, hoping to relieve some of the pressure on it. Then, with the edge of the rasp, I etched a groove across the top of the crack, which at least would slow down its growth. I removed the rope and watched the horse for a bit. He seemed to be walking a little better. I poured as much water as I dared risk into my hat and let him drink it. He wanted more, but I couldn’t take the chance this far from water.

The gelding must have felt better, since he flopped down and rolled happily back and forth for a few seconds. He lunged back to his feet, shook the dust off, and began looking for whatever forage he could find.

I mounted Charcoal again, and we resumed our northwest journey, with the gelding walking slowly behind us. Worn out and with a split hoof, he couldn’t keep up, but he trailed along anyway. The last time I had been out this way, there’d been a small river maybe five miles or so farther along. I hoped it hadn’t gone bone dry this summer.

An hour and a half later, in the dim light of dusk, I could just make out a man stretched out beside the rocky riverbed … either dead, unconscious, or just lapping up water. Hutchins? Probably.

Copyright ©2012. Walter P. Shiel. All Rights Reserved.

Drop in tomorrow for the rest of the story, which will soon be published in a collection of Everett Ross short stories, prequels to Once A Knight.

Writing from the Woods

- Walt Shiel's profile

- 22 followers