Meet the Guantánamo Prisoner Who Wants to be Prosecuted Rather than Rot in Legal Limbo

Throughout the spring and summer, while the prison-wide hunger strike at Guantánamo raged, taking up most of my attention, as I reported prisoners’ accounts, and campaigned to get President Obama to release the 86 prisoners cleared for release in January 2010 by his own inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, I missed some other developments, which I intend to revisit over the next few weeks, beginning with an article by Jess Bravin for the Wall Street Journal in July.

Throughout the spring and summer, while the prison-wide hunger strike at Guantánamo raged, taking up most of my attention, as I reported prisoners’ accounts, and campaigned to get President Obama to release the 86 prisoners cleared for release in January 2010 by his own inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, I missed some other developments, which I intend to revisit over the next few weeks, beginning with an article by Jess Bravin for the Wall Street Journal in July.

Bravin, the Supreme Court correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and the author of the acclaimed book The Terror Courts: Rough Justice at Guantanamo Bay, wrote an article entitled, “Guantánamo Detainee Begs to Be Charged as Legal Limbo Worsens,” which perfectly captured the Alice in Wonderland-style absurdity of the prison, eleven and half years after it opened, with the remaining 164 prisoners no closer to securing justice than they were when George W. Bush set up the prison, which, at the time, was intended to be a place where they could be held without any rights whatsoever.

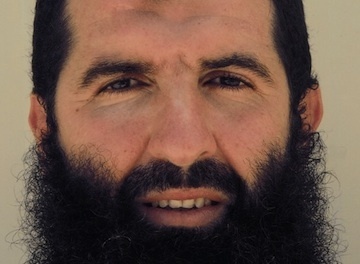

Highlighting one aspect of this ongoing injustice, Bravin looked at the case of Sufyian Barhoumi, identified in his article as Sufiyan Barhoumi, who, as he described it, “has decided to plead guilty to war crimes, throw himself on the mercy of the court and serve whatever sentence a US military commission deems just.” As Bravin added, however, “There’s just one problem: The Pentagon refuses to charge him.”

Barhoumi is one of 63 prisoners who have had their cases ruled on by judges in the District Court in Washington D.C. since the Supreme Court ruled in June 2008 that they had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights, and is one of 25 whose habeas petitions were not granted by the judges involved — although the appeals court later intervened to reverse or vacate some of the 38 victories for the prisoners, eventually rewriting the rules so that no more prisoners could have their habeas petitions granted.

Barhoumi’s habeas petition was turned down in September 2009, and his appeal was denied in June 2010, which I reported at length in an article at the time, entitled, “In Abu Zubaydah’s Case, Court Relies on Propaganda and Lies.” An Algerian, he was seized on March 28, 2002, in a house raid in Faisalabad, Pakistan, that led to the capture of Abu Zubaydah, the gatekeeper of a training camp in Afghanistan who was mistakenly regarded as a senior figure in al-Qaeda and was the first victim of the Bush administration’s torture program for so-called “high-value detainees,” even though he was not a member of al-Qaeda at all.

Bravin’s focus on Barhoumi’s case was timely, because of two recent — and surprising — decisions in the appeals court in Washington D.C., overturning two of the only convictions secured in the military commission trials at Guantánamo since they were revived by Vice President Dick Cheney in the wake of the 9/11 attacks (of Salim Hamdan, a Yemeni who had worked as one of Osama bin Laden’s drivers in Afghanistan, and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, a Yemeni who had made a propaganda video for al-Qaeda). As Bravin explained, “Federal judges in Washington reversed the military commissions’ convictions of detainees Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul because the charges prosecutors filed — conspiracy and material support for terrorism — weren’t war crimes.”

As Bravin continued to explain, “Those two charges were the only ones prosecutors believed they could prove against more than a dozen detainees, including Mr. Barhoumi.” The Obama administration has appealed, but as Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, the chief prosecutor of the military commissions, explained in June, “the maximum number of prisoners that the US military intends to prosecute, or has already prosecuted, is 20 — or just 2.5 percent of the 779 men held at the prison since it opened in January 2002,” as I stated in an article at the time — down from the 36 recommended for trials by Obama’s task force, plus the three prosecuted under George W. Bush.

With seven men already prosecuted, and eight currently charged or facing trials, that leaves a maximum of five other men who can conceivably be tried, and it is uncertain if one of those five will be Sufyian Barhoumi. Highlighting the absurdity of the predicament facing the men recommended for prosecution by the task force, Barhoumi is one of 23 men not charged, but listed as being recommended for prosecution, in an official document that was released, through FOIA legislation, in June this year, meaning that 18 of those men are likely to find themselves in the same limbo as Barhoumi.

As Bravin proceeded to explain, “Guantánamo prosecutors routinely filed conspiracy and material support charges because they are easier to prove than tying suspects to a particular attack.”

Capt. Justin Swick, Barhoumi’s military defense attorney, told Bravin, “For years, your ticket out of Guantánamo was being found guilty,” noting that Salim Hamdan was repatriated five months after his conviction for material support in August 2008. Capt. Swick added, “Now there’s nothing to be found guilty of.”

Analyzing this disgraceful situation, Bravin noted, “Elsewhere in the American justice system, suspects go free unless prosecutors file charges. In Guantánamo, the opposite is true: Detainees who aren’t charged and are presumed innocent under the Military Commissions Act of specific war crimes nevertheless face indefinite detention because the Pentagon has classified them as enemy combatants.”

He also stated that Barhoumi’s lawyers had explained to him that prosecutors “won’t file charges unless Mr. Barhoumi first testifies against other detainees.” Another military defense lawyer, Lt. Col. Richard Reiter, said, “They are going to exploit their ability to hold him under indefinite detention and try and force him into cooperation. I would classify it as an abuse of prosecutorial discretion.”

Defense lawyers also stated, as Bravin put it, that “they believe prosecutors are desperate for live courtroom testimony against Mr. Zubaydah — something considered far more credible than hearsay statements taken by interrogators and other evidence that could be undermined by controversial CIA practices.”

Through his attorneys, Barhoumi himself responded to questions posed by Brevin. “I want to tell my story, but they put up obstacles,” he said, adding, “I don’t have a black heart against America.”

Capt. Swick, telling Barhoumi’s back story, told Bravin that, “like many North Africans, Mr. Barhoumi crossed the Mediterranean in the 1990s to seek his fortune in Europe. Opportunities were elusive, and in 1999 he left Britain for Chechnya, intending to join the Muslim insurgency against Russian rule.” He then “followed the jihadist trail to Afghanistan to attend training camps, where he lost four fingers and mangled his left thumb while practicing with explosives.”

Barhoumi explained the circumstances to a military review board during the Bush administration. “It was a small bomb buried, a mine,” he said. “While digging, I pressed it accidentally.”

After the 9/11 attacks, and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, Barhoumi fled to Pakistan. He said that “he had been in Faisalabad around 10 days when the safe house was raided by Pakistani authorities, who captured about 20 Arabs and turned them over to the US,” as the Wall Street Journal explained. Barhoumi said that he “was in the wrong place” at the wrong time, adding that “he had never seen Mr. Zubaydah before arriving at the safe house, and barely after that.”

Under George W. Bush, Barhoumi was accused of conspiracy, allegedly for “training two other occupants of the Faisalabad house in remote-control explosive triggers,” but that case collapsed when, in June 2006, the Supreme Court ruled that the commissions were illegal.

When they were ill-advisedly revived under President Obama, Barhoumi almost secured a plea deal that would have led to him receiving a 20-year sentence, defense lawyers explained, but the deal “fell apart on a dispute over whether Mr. Barhoumi should get credit for the years he has already spent in prison.”

In the wake of the appeals court rulings dismissing the convictions of Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, the charges against Barhoumi were dropped. As noted previously, the Obama administration has appealed, but, as Bravin pointed out, “it could be years before the issue is ultimately resolved.” Capt. Swick explained that Barhoumi’s defense team was informed on January 31 that the charges had been dropped.

He added that the news “dismayed” Barhoumi, who, after meeting with his lawyers, “decided to invite the prosecutors to file any charge they wished, and he would plead guilty. At sentencing, prosecutors could argue for any sentence up to life imprisonment, and Mr. Barhoumi could seek a lesser penalty.”

Capt. Swick also explained, “He would address them directly in English, which he’s learned since he has been here, explain the mistakes that he made and his plans for the future.”

Capt. Swick also explained that, in February, the defense team met with prosecutors to propose the plan. However, just eleven days later, the disappointing response was delivered. There would be “no charges unless Mr. Barhoumi testified in court against other detainees.”

On Barhoumi’s behalf, Capt. Swick refused. As he explained, his client is “willing to work with this system and plead guilty because it is his only alternative to indefinite detention without trial, but he won’t help convict someone else in a system he believes is illegitimate.”

Responding to the realization that he was trapped, with no apparent way to get out of Guantánamo at all, Barhoumi, who has been described as “highly compliant” by the authorities, joined the hunger strike that has been raging since February. Capt. Swick said that when he had visited Barhoumi in May, he “had lost about 50 pounds,” and was “subsisting on honey, tea and liquid supplements.” Like the other hunger strikers, he had been “placed in solitary confinement” and was allowed just “two hours a day outside his cell.”

And like all the prisoners, whether the 84 cleared for release but still held, or the others recommended for trials that are not happening, or for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, Barhoumi evidently concluded that, whatever category he was supposed to be in, the reality is that everyone still held at Guantánamo is actually trapped in a living tomb, a disgraceful situation that must be brought to an end.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers