WRITING: How to Avoid a Saggy Middle

Saggy Middle Syndrome.

We all know what it is. A novel that starts brilliantly well – vivid, intriguing and compelling – yet somehow, around the middle of the book, you find yourself beginning to yawn. You check the pages to see how many are left before the end of the chapter. You might even put the book down and pick something else up instead.

It happens in series of books too. The first couple of books are great – you rushed out to buy the next one as soon as you finished the first – but then, around Book 3 or 4, you begin to lose interest. The book seems predictable, stale, and far too long.

Yep, that’s Saggy Middle Syndrome.

I always tell my writing students:

The first scene is the most important scene in the book.

The last scene is the second most-important scene in the book.

The middle scene is the third most important.

Yet many, many writers just think of it as just another scene.

I don’t. I think about it very deeply and very carefully.

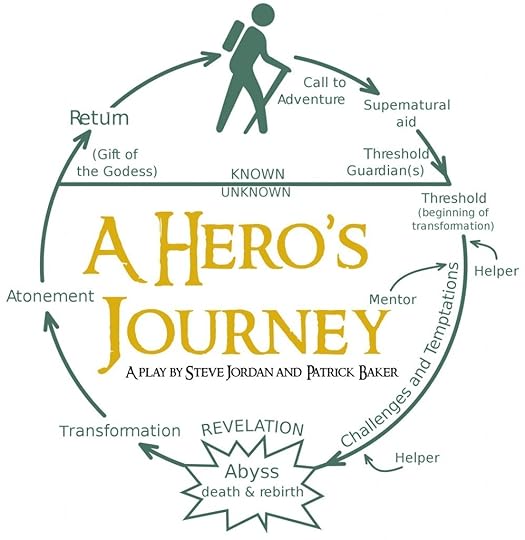

In Campbellian story theory, the midpoint is The Belly of the Whale.

It is the darkest point of the story, a time in which it may seem that all is lost and the hero cannot go on. It is a time of psychological darkness, or emotional despair, a time in which the hero surrenders all hope.

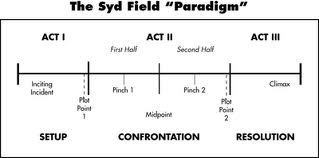

Syd Field, the grandfather of screenwriting theory, calls it the Midpoint Reversal: ‘An important scene in the middle of the script, often a reversal of fortune or revelation that changes the direction of the story.’

I like this term as it expresses something of what I believe about this most significant of turning points, the second major crisis in your story.

The midpoint must be a pivotal moment in the story, a kind of psychic shift, a hinge that joins together the two halves of the book. I believe there should be some kind of epiphany, a moment of clear-sightedness in which the hero realises the cost of the path to which they have committed themselves. The hero must either find the courage to go on in their chosen path, or choose another way. The reversal does not need to be a complete face-about, but it does need to show a change in the hero’s outlook.

I like my midpoint reversal to be set somewhere dark, somewhere claustrophobic, somewhere dangerous, but this does not always need to be the case. It can be high noon in a desert, or dawn in a baby’s bedroom. The Midpoint Reversal is always about the character’s inner journey. Often the Midpoint Reversal is a symbolic gateway to another place, a new direction, a new landscape – either literal or metaphorical – or a new understanding of the truth. It can also foreshadow the final showdown – often the midpoint is where the hero tries to achieve whatever it is he or she wants, but fails. However, in that failure may come the realisation of what needs to be done in order to triumph, even though the cost may be high.

For the reader, it should signal an acceleration of the plot, a raising of the stakes, a deeper understanding of the hero’s dilemma. It should throw the story into another gear, making the reader fear for our hero more intensely than ever before.

I’m writing this writing post today, because I am writing the middle scene of the middle book in a five-book series (ie I’m halfway through writing Book 3). The Midpoint Reversal of this book is also the mid-point of the whole combined narrative arc and so it has to carry a double burden. It needs to be a significant pivotal moment, a crisis of the soul, for the whole five-book series as well as for this particular novel.

So excuse me while I go and exercise all my wit, ingenuity and creative craft to make sure that my novel has strong core muscles and a six-pack to be proud of.

Published on September 03, 2013 18:12

No comments have been added yet.