Demon of Eclipses & Illusions – Part 1/9

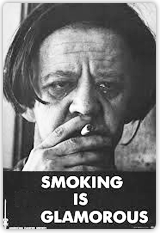

Strolling down Manhattan’s Broadway in the early 1990s, I stopped to stare at a dramatic hoarding, the elements of which I shall attempt to recapitulate for you: a smoldering cigarette hangs out the corner of the mouth of an older woman with a halo of frizzy gray hair; her heavily made-up face barely masks a mesh of wrinkles and furrows, her cunning eyes are narrowed as a shield against the rising smoke, her cracked smoker’s lips are painted a bright red; as for the ironic caption below, it reads: Smoking Is Glamorous.

Strolling down Manhattan’s Broadway in the early 1990s, I stopped to stare at a dramatic hoarding, the elements of which I shall attempt to recapitulate for you: a smoldering cigarette hangs out the corner of the mouth of an older woman with a halo of frizzy gray hair; her heavily made-up face barely masks a mesh of wrinkles and furrows, her cunning eyes are narrowed as a shield against the rising smoke, her cracked smoker’s lips are painted a bright red; as for the ironic caption below, it reads: Smoking Is Glamorous.

Oh what a powerful message! I thought, even as I dragged deeply on the fragrant Nat Sherman cigarette hanging, Bohemian style, out of the side of my own mouth. But despite the irony of that moment, that harsh image continued to hover on the fringes of my insubordinate mind, warning me how I might end up if I didn’t quit smoking.

Back in India, two upper-class women of my mother’s generation had ended their lives looking pretty similar to the hag on the hoarding. Both had thumbed their noses at convention and taken up smoking and drinking with a vengeance. Both had died heavily burdened by the circumstances of their lives, their striking beauty a sad memory; despite medical warnings, the mounting concern of their respective families, and their own fierce wills, neither had ever been able to quit either ciggies or booze.

Given their disinterest in consciousness-raising the eastern way, I could see why it would be easy to end up like that. But what about me, driven by a passion for yoga, meditation and mysticism? Why couldn’t I put a halt to a nauseating and expensive habit that was literally choking the prana out of me? Oh yes, I’d stop for months at a stretch — because I felt like a hypocrite for raving about yoga in public while destroying my lungs in private, or because of the horrid effects of nicotine poisoning on my sensitive body and mind; then some event or feeling would trigger my next binge, and I’d be off to the races.

What eerie grasp did smoking have on the human psyche? And why had so many celebrities — particularly in the days before the barrage of nicotine warnings hit the international scene — clung to smoking as part of their public image? Jean-Paul Sartre chain-smoked Gauloises, Albert Einstein, Douglas MacArthur and Bertrand Russell were rarely seen minus their pipes, and Sigmund Freud committed doctor-assisted suicide on account of oral cancer caused by heavy smoking. Writers seem ultra susceptible to the demon of smoke — Richard Klein’s book Cigarettes are Sublime addresses the grip of tobacco over the French literary world, while Kurt Vonnegut wrote about his ciggie addiction. None of these men could be accused of possessing low IQs — so why did none of them jettison this destructive habit?

What eerie grasp did smoking have on the human psyche? And why had so many celebrities — particularly in the days before the barrage of nicotine warnings hit the international scene — clung to smoking as part of their public image? Jean-Paul Sartre chain-smoked Gauloises, Albert Einstein, Douglas MacArthur and Bertrand Russell were rarely seen minus their pipes, and Sigmund Freud committed doctor-assisted suicide on account of oral cancer caused by heavy smoking. Writers seem ultra susceptible to the demon of smoke — Richard Klein’s book Cigarettes are Sublime addresses the grip of tobacco over the French literary world, while Kurt Vonnegut wrote about his ciggie addiction. None of these men could be accused of possessing low IQs — so why did none of them jettison this destructive habit?

Witness to the Fire, an amazing work by Jungian analyst Linda Schierse Leonard, offers one answer: the fascinating link between creativity and addiction. Through the lives of writers such as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Eugene O’Neill, Jean Rhys, and Jack London, as well as the experiences of ordinary folk, Leonard proves that those who shake off the rusty chains of addiction by harnessing the forces of creativity are likely to discover a sweet freedom. Bottom-line, Leonard’s message is that addictions “veil” our creative potential; addicts can reclaim the power that fuels their dependency and create a new life sizzling with joy and creativity.

From my own experience, as well as by studying the lives of a variety of creative folk I’ve had the privilege to encounter, I find Leonard’s conclusions right on the mark: if we are willing to let go of all the myriad ways in which we tamp down on our primal energy, our creativity flares back up, like the phoenix rising from the ashes of defeat, and we are amply rewarded for the apparent sacrifice of our hedonistic pleasures.

From my own experience, as well as by studying the lives of a variety of creative folk I’ve had the privilege to encounter, I find Leonard’s conclusions right on the mark: if we are willing to let go of all the myriad ways in which we tamp down on our primal energy, our creativity flares back up, like the phoenix rising from the ashes of defeat, and we are amply rewarded for the apparent sacrifice of our hedonistic pleasures.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 7

Part 8

Part 9