The Curious Other: Confronting Racism In Our Work

Here’s the plot summary of Date Night, as provided by the film’s official website: Phil (Steve Carell) and Claire Foster (Tina Fey) are a sensible, loving couple with two kids and a house in suburban New Jersey…In an attempt to take date-night off auto-pilot, and hopefully inject a little spice into their lives [they go to Manhattan’s] hottest new restaurant and steal a couple’s no-show reservations. The real [couple], it turns out, are [thieves] who are being hunted down by pair of corrupt cops….Phil and Claire realize their [date] has gone hilariously awry, as they embark on a wild and dangerous series of adventures to save their lives…and their marriage.

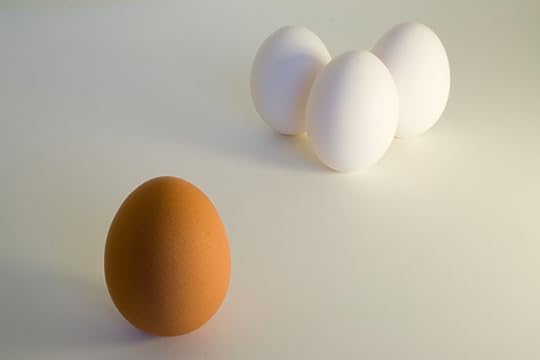

Here’s the plot summary, provided by me: Two sheltered white people venture into the city for the night, see a lot of non-white people and get scared.

To me, this movie is about race. Not consciously. Not directly. But what else do you call a story where the heroes are white, all their friends are white, and the people in their book club are white. It is only when the heroes leave their comfy suburb to go into New York City that they encounter other races, namely a handful of African-Americans and one Italian guy (who eats spaghetti while bossing around his hit men.) When you enter the city, the movie seems to be saying, you meet The Ethnic Other. And the world of the Ethnic Other is filled with violence, danger, and corruption.

When, at the end of the film, a newly loving Phil and Claire return to their clean suburb unscathed, the viewer is expected to exhale a sigh of relief. Oh, thank God! They’re safely back among rich, white people!

What interests me about this problem is not only the issue of racism itself, but how screenwriter may not have seen the racism. And, for that matter, none of its editors, sound mixers, producers or actors may have seen either. This led me to wonder: To what degree does a writer need to set her own moral and ideological cards in order before crafting a story?

I was once in a writing workshop with a man who wrote stuff that I found downright offensive. All the poor people toted guns. They drove pick-up trucks. They didn’t read and they drank cheap beer. When I suggested that this writer flesh out his “working-class” characters a little more, he looked at me with a shocked stare that all but said, “But that’s how these people are.”

The funny thing was, apart from his ignorance, he was actually a fine writer. He perceived the nuances of human interaction, the drama of daily life, and articulated these things beautifully. Yet he had a particularly narrow-minded view in regard to the working poor. He could not see anything wrong with his portrayal of these “simple folk.”

At the time I thought he needed to go out and get himself a social education. But I also turned the question onto myself—what beliefs might I harbor unwittingly? What sorts of –isms might I be promulgating through my work? Not because I believe them necessarily, but because I’ve absorbed cultural ideas without properly challenging them. A black boy playing basketball. A gay man wearing designer clothes. A liberal going to a museum.

The list goes on. The stereotypes go on. The commercials we see embodying these stereotypes go on and it can be frightening to realize how frequently these stereotypes, and the dangerous ideologies behind them, can appear in one’s work. Equally frightening is to see how potential plot points might hinge on the very –isms we are trying to avoid. (See Judith Butler’s brilliant feminist critiques of Hemingway for more on this topic.)

Perhaps the only way to avoid narrow thinking in our writing is to avoid narrow thinking in our lives. And maybe, as writers, when confronted with cultural difference, it’s in our best interest to get closer, rather than run away.

Originally appeared on Beyond the Margins May 3, 2010

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers