Guns and cruising boats

Copra boat at the dock in Taiohae Bay, Nuku Hiva, Marquesas with gendarme’s post on the hill behind

by Christine Kling

Much has changed in the world of cruising sailboats between 1975 and today, but one thing that hasn’t changed is the question that all the non-sailors always ask: “Aren’t you afraid of pirates?” And it is that fear primarily that leads sailors to make a basic decision: whether or not to carry firearms aboard.

Guns can be a big problem for cruisers because most countries of the world have strict gun control laws. This means that when you arrive, if you carry guns, you must declare them to customs. Customs will then take them and hold them until you clear out. Once you get the guns back, you must leave immediately. This means that when you are cruising in the waters of that country, close to land, the time when you are most likely to need your guns, you can’t have them aboard, and you need to return to the same port where you entered to pick up your guns to depart. All that leads many cruisers to either not carry guns at all — or to find a very good hiding place on their boats and choose to not declare their guns to customs. The problem is that if they are found out, the penalty can be fines, confiscation of the boat and/or jail.

When we arrived in Taiohae Bay at Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas in May of 1975, we had no guns aboard because Jim didn’t want to have the hassle with customs. Every cruiser has to make that basic decision, and that was where Jim fell on the gun question. During the next couple of years that we cruised the South Pacific, we never felt threatened by local population of the islands and we never encountered pirates of any sort.

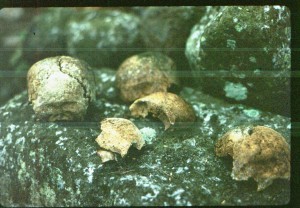

Skulls we found between the stones of a Marquesan marai remind us of how recently they were cannibals

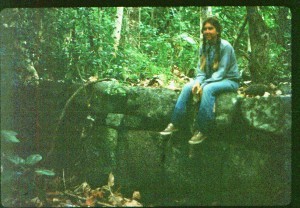

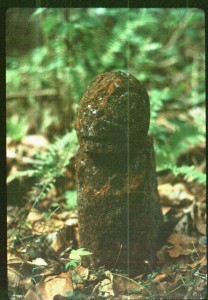

In fact, the people of the Marquesas were extremely friendly. The main drag in the village was a dirt road and the gathering spot was at Rui, the baker’s house/shop where one could buy lovely French baguettes and cold beer, and since I spoke fluent French from having spent a year in France as a foreign exchange student, I could get us caught up on the local gossip. We were having a terrific time visiting with the locals. Two kids offered to take us up to swim at the base of the waterfall high up in the valley and when they showed up, they had a horse for me to ride. What I found so amazing about this trip was there seemed to be archeological treasures just lying around the jungle everywhere. We saw numerous stone tikis scattered throughout the jungle. On this long hike, the kids stopped and showed us a marai, a large rectangular stone platform that as recently as 100 years before had been used as a sort of temple for meetings, ceremonies, rituals and sacrifices. Before the arrival of Christian missionaries put a stop to it, the Marquesans had been cannibals, and the kids pulled out skulls from the stones of the marai to prove it.

It was one afternoon when we were sitting outside Rui’s having a beer that Mark, the other crew aboard the Kathi II met the skipper of the big motorsailor I’ll call the Other Boat. They hit it off and the fellow invited Mark to go goat hunting with him. It seems that the north coast of Nuku Hiva is very steep and mountain goats clamber around on the cliffs. The locals go around in their open wood skiffs and shoot from their boats. The cliffs are so steep that once shot, the goats tumble into the sea.

It was one afternoon when we were sitting outside Rui’s having a beer that Mark, the other crew aboard the Kathi II met the skipper of the big motorsailor I’ll call the Other Boat. They hit it off and the fellow invited Mark to go goat hunting with him. It seems that the north coast of Nuku Hiva is very steep and mountain goats clamber around on the cliffs. The locals go around in their open wood skiffs and shoot from their boats. The cliffs are so steep that once shot, the goats tumble into the sea.

The next morning, the skipper of the Other Boat arrived at daybreak in his fancy dinghy to pick up Mark. He handed Mark a rifle and a burlap copra sack. He told Mark to keep the rifle hidden because he had not declared the guns. Off they went to meet the locals on the beach and transfer into the hunting boat. We couldn’t help but notice that about three inches of barrel was sticking out of Mark’s copra sack.

I don’t know if it has changed since we were there, but we noticed an odd relationship between the native Marquesans and the French. The locals who were former cannibals and fierce fighters resented their colonizers and held no love for them. The few French gendarmes were obviously nervous about their tenuous hold on islands where they were grossly outnumbered and not beloved. On the other hand, the locals were also quick to tattle to the authorities on both their neighbors and on the yachts.

So it was later that afternoon when Jim and I were sitting on the steps of the baker’s house drinking our cold beers that we saw the triumphant hunters return. They had bagged a goat and the Marquesan men were all smiles. There was only one man on the island who was permitted to own a gun and ammunition was scarce. Thanks to some sailors who just wanted to go on the hunt, they were taking home meat for their families. The skipper of the Other Boat collected his guns and disappeared in his dinghy while Mark joined us for a beer. Just as he started to regale us with stories of the hunt, we heard the distant high-pitched wee-hoo, wee-hoo, wee-hoo of a European police siren. The gendarme truck (the only motor vehicle on the island) pulled up in a cloud of dust. The gendarmes climbed out, grabbed Mark, threw him in the back of the truck and took off back up the hill.

So it was later that afternoon when Jim and I were sitting on the steps of the baker’s house drinking our cold beers that we saw the triumphant hunters return. They had bagged a goat and the Marquesan men were all smiles. There was only one man on the island who was permitted to own a gun and ammunition was scarce. Thanks to some sailors who just wanted to go on the hunt, they were taking home meat for their families. The skipper of the Other Boat collected his guns and disappeared in his dinghy while Mark joined us for a beer. Just as he started to regale us with stories of the hunt, we heard the distant high-pitched wee-hoo, wee-hoo, wee-hoo of a European police siren. The gendarme truck (the only motor vehicle on the island) pulled up in a cloud of dust. The gendarmes climbed out, grabbed Mark, threw him in the back of the truck and took off back up the hill.

Jim and I each took a gulp of beer and he said, “Hmmm, now isn’t that interesting.” But before we even finished our beers, we heard that siren start up again, and down swooped the truck. This time they were looking for the captain of the Kathi II. In both encounters I had translated what the gendarmes wanted, so I was invited to join Jim in the back of the truck.

Moments later, I found myself in the stifling hot police station sitting on a chair with Jim on one side and Mark on the other. The head honcho gendarme was sitting behind the desk in front of us. He wore a Peter Sellers Pink Panther mustache and that high hat that looked a bit like an upturned saucepan on his head.

“Mademoiselle,” he would say to me. “This man,” he indicated Mark, “was observed with a rifle in the village and he says it belongs to him. The captain of your vessel did not declare any guns. What does your captain say to this.”

I would turn to Jim and translate. Jim stated, “I do not carry any guns aboard my boat and I have never seen that gun before today.”

Then Mark would say it was his gun, and Jim would lean around me and glare at him.

I would translate and the gendarme would say something like, “C’est pas possible,” and throw his hands into the air. “Do you expect me to believe that it is possible this man hid a gun aboard your boat?”

I’d throw my hands into the air and say in French, “I’m just the translator here.”

After nearly two hours of sweating us through this interrogation with Jim and Mark each repeating his line over and over and the gendarme threatening to arrest Jim as a gun smuggler, they finally let us go. We were told to return the following afternoon with the boat papers and our passports.

Once outside the office, we got the real story from Mark. The skipper on the Other Boat had offered him a paid crew position on the luxurious motor sailor, and Mark didn’t want to get him in trouble.

The next afternoon we took our documents in, but earlier in the day Mark had gone to the gendarme’s office with the skipper of the Other Boat and applied to change from our crew list to his. When Jim and I arrived, the officer was much nicer. The guys still stuck to their paradoxical stories, but the gendarme seemed to have figured things out. We were instructed to attend a court hearing in Papeete, the capitol of French Polynesia, on a particular date and set free.

A month later when we finally got to Papeete, the Other Boat had beat us there. His boat had been searched from stem to stern on arrival and they discovered not only guns, but also two small dirtbike motorcycles that were undeclared. The last we heard, the incident was going to cost him a small fortune just to stay out of jail. When we went to court, we were cleared of all wrongdoing and we got our papers back.

When we returned to the boat med-moored to quay on the Tahiti waterfront, we ran into the famous sailor/author Bernard Moitessier wearing a sarong, and I saw my old friend Jack who had sailed his folk boat down from Maui. I was beginning to feel a part of the cruising community, and we were now free to sail the rest of the Society Islands.

Fair winds!

Christine

Share on Facebook