Science fiction vs. fantasy: what’s the difference?

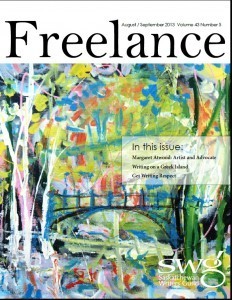

My column for the latest issue of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild magazine

Freelance.

..

My column for the latest issue of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild magazine

Freelance.

..

Although science fiction and fantasy often overlap in both bookshelves and readership, they aren’t actually the same genre.

Exactly where you draw the line between them, of course, is a matter of some debate. (Because, well, what isn’t?)

Just do a Google search on “difference between science fiction and fantasy” and see how many hits turn up. (As of this morning, using that exact search term, 88,400. And that’s just one way of phrasing the question.)

Bestselling author Orson Scott Card famously said that “fantasy has trees, science fiction has rivets.” But that’s less true than it used to be: my own fantasy novel Magebane has rivets (or at least airships) and trees, and there are plenty of metaphorical rivets in the very popular sub-genre of urban fantasy, where computers, cars and commuting magically mingle with witches and wizards and wands.

In truth, the line between the genres is blurred, not bright: and yet there is a line, and although many writers step across it with abandon, they always know where it is.

I should know, because I’ve been leapfrogging that line myself all year.

I’ve got two new novels coming out this year. One is science fiction, and one is fantasy. I’ve been working on them concurrently. The science fiction novel, Right to Know, happened very quickly: Bundoran Press underwent an ownership change, the new publisher, Hayden Trenholm, asked me if I had anything I could send him, I sent him Right to Know, he bought it, and it’s out now.

That meant some pretty fast-paced rewriting…and rewriting that overlapped my final rewrites for Masks, my new fantasy novel, first in a trilogy, coming out in hardcover under the pseudonym E.C. Blake from my New York publisher, DAW Books, in November.

Working on both at the same time meant constantly switching my brain from science fiction to fantasy mode, which rather crystallized for me the differences between the genres.

It’s not an original insight, by any means—lots of people have made this point—but in brief, the difference between science fiction and fantasy is that the events in science fiction could plausibly take place in the real universe: the events in fantasy could not.

I know, I know, that sounds like a bright line, but of course it’s immediately smudged by the many liberties liberties science fiction writers take with reality as we know it. Case in point: Right to Know is about an enormous starship, the Mayflower II, packed with 10,000 people, fleeing Earth at a constant .3 g acceleration, which gets it close to the speed of light in remarkably short order. So far so good: there’s nothing inherently impossible about that. And the time dilation effects of such travel are also established scientific fact: while aboard the ship some 30 years pass, back on Earth 400 years fly by—time enough for humans to develop faster-than-light travel (a la Star Trek), leapfrog the Mayflower II, and be waiting for it when it arrives at its destination. And there I blur the line, for faster-than-light travel may very well be impossible, no matter how well-established it is in science fiction, so the moment you introduce it you’re already edging toward fantasy.

But—and here’s the big but—science fiction authors have this ace in their authorial poker hand: it’s undeniable that scientific process has resulted in many things once thought to be impossible in fact becoming possible. So science fiction is still based on our understanding of the universe as a place that obeys certain physical laws that, through the scientific process, humans can learn to understand and manipulate.

Now consider my fantasy novel, Masks. It’s about a world where, at age 15, everyone has to don, whenever they go out, a Mask that reveals, via magic, any seditious thoughts or antisocial attitudes to the omnipresent Watchers of the monarch. Magic is something that can be mined and distilled, a potent power that only a few Gifted can use. The heroine is more Gifted than anyone knows—but her Masking fails and she is sent into horrific exile.

You can’t get from our world to that world. No amount of scientific advancement will give you magic.

And that is the ultimate bright line. Science fictional worlds are contiguous with the real world: you can imagine getting there from here (or, in the case of alternate history, you can imagine we could have gotten there instead of here). Fantasy worlds are worlds made up out of whole cloth. They may look like our world (a la urban fantasy), they may borrow from our world (all those feudal kingdoms), but you can never get from here to there…

Except, of course, through books.