The Ordinary Weather (Part II)

8-23

ECONOMY: At the second joint funeral—my mother couldn’t leave the hospital for the first, so we had two (times two)—the preacher offered re my father and grandmother: “I can sum up each of their lives in three words: they cared, they shared, and they loved.”

That’s 1.5 words per life, less than a word per eulogy. Fuck that guy for letting what he wanted to say prevent him from saying anything at all.

—

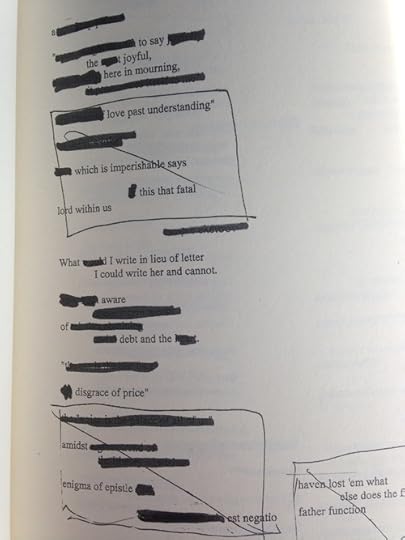

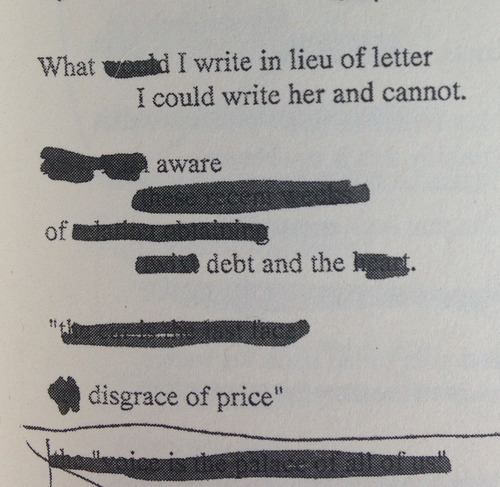

In “Election,” the second section of The Ordinary, both “debt and the disgrace of price” are problems of the letter, of the attendant risks of offering your two cents. (My dad calling back: don’t let your mouth write a check your ass can’t cash.) One elects to get legible, to chime in or sum up (in however many words), or one elects to abstain, to keep quiet. Both are arguably just as risky, but Brazil’s book deploys a third strategy. Seen here as a kind of textual self-scarification, the blacked-out and crossed-out text reads less and less (to me) like facsimile or erasure. Instead, redaction here seems to want a critique of the effort to get legible in the first place, seems even to offer a kind of apology.

Letter turns to coin, but what if I shred the bill as I hand it over?

So, this writing “in lieu” of what could (but can’t) be written: a text that questions its own rationale for being here to begin with, its presumption to make an account. Am I doing the right things (i.e.—are my own accounts in order)? (& “what can they have meant?” XXXI)

8-24

Like Spicer’s Gwenivere in The Holy Grail: “I am sick of the invisible world and all its efforts to be visible” (Collected, 342). The complaint runs directly counter to the urge to say it aloud, and the poem happens somewhere in the interim.

8-25

I don’t think David’s drafts are included here in the interest of transparency, but rather, of immediacy. We’re shown the material, the poem-as-drafts, so that we can (hopefully) engage an event, so that we can get at some part of working that exceeds ‘the work.’

My grandfather died six years ago, and one of the upsets of the storm in May was that virtually none of his carpentry survived intact. The relief workers collected chunks of splintered wood (keep anything, we told them, that looks handmade), and much of it sits now in storage, will likely end up in the trash.

Seeing what the storm didn’t destroy beyond recognition was almost always a punch in the gut: like the hope chest my grandfather built for my grandmother, which I could precisely locate at the moment when the storm hit—it was between where my father sat on my grandmother’s bed and where my mother stood in the doorway to the room. In the hospital, my mother recounted the story compulsively whenever anyone new came to visit. What they’d done in the hour before, where they were when the entire house and its contents were tossed 300 yards. The chest probably isn’t repairable, but that it was still legible as itself in the aftermath took the wind out of me.

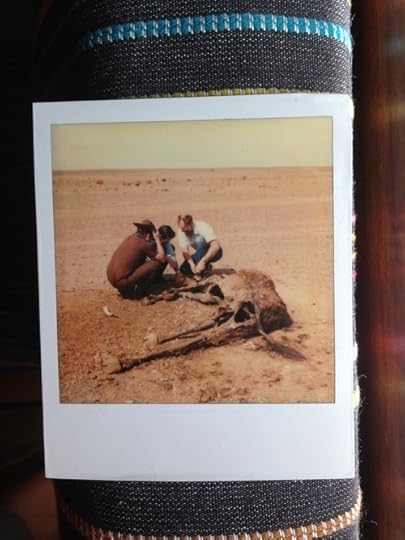

Other items surfaced that didn’t hurt as much to confront, but that still had the effect of making a story I received second-hand somehow suddenly immediate. My grandmother used to tell of a group date that got interrupted when my grandfather stopped the car to pull teeth from a dead camel. Working for El Paso Products (natural gas) had taken them to Algeria in the late seventies, and one evening my grandparents were out with other couples from the gas plant when grampa saw a camel carcass, and thus potentially unclaimed ivory (the teeth). It was one of my favorite (because most perverse) stories about their time abroad, and she always swore there was a photo but could never find it.

I was at the debris site helping my uncle sift through some of what had been recovered when I saw what remained of the wooden chest. Immediately after, I picked this up from a pile of photos, and felt like my grandmother was finishing the story (grampa’s the pompadour in the middle):

8-26

In The Ordinary, there are blacked-out passages, but there are also chunks of text that have been more hastily circled and slashed through. As a drafting gesture, this would seem to suggest complete elision, but included as such, as the poem, these passages remain almost entirely visible. A reader has a choice: read these still legible passages or move on. If this were a more sustained critical engagement, I think it’d be useful to examine the distinction between redaction and circle/slash, if only to complicate this notion I’m nursing that “immediacy” is what this poem’s after—an immediate, if not unmediated, experience of event. There’s staging in David’s book, but I don’t think the book presumes to be the thing it’s a facsimile of, nor is it simply an effort to put indeterminacy in play (though it’s in a tradition of like efforts).

My take: there’s what we elect (what we keep and discard, what we protect or raise up, what we ignore), and then there’s weather (undemocratic). Subject to weather, our elections (in writing, in reading) are readily overturned. There are moments in David’s book when I feel myself exposed to the elements:

Read Part I of this piece here.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers