Hip-Hop’s Anxiety: Inhering Influence, Testimony, & the Test of Time by Wilfredo Gomez

Hip-Hop’s Anxiety: Inhering Influence, Testimony, & the Test of Time

by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Hip-Hop’s Anxiety: Inhering Influence, Testimony, & the Test of Time

by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)Yo too many songs/weak rhymes that’s mad long/make it brief son/half short and twice strong—GZA “As High as Wu-Tang Get”

Not this time/but next time/I’mma name names/LL shittin’ from on top of the game/I shot ya—LL Cool J “I Shot Ya”

I throw some ice for the nicest MC/But you can tell Kendrick Lamar/the King of New York is me/Bloomberg—Jasiri X “Mayor Bloomberg Responds to Kendrick Lamar’s Control Verse

“You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become a villain”—Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight

Before getting into the meat of this piece, take a moment and think about your favorite “diss” song. Do you have some hip-hop quotables? Do they stand the test of time? Which MC’s were at the center of that beef and why? The last quote serving as an epigraph to this piece is poignant on a number of levels, the most obvious one being that Harvey Dent, a symbolic marker of justice in fictitious Gotham City, died as Two-Face, a villain, whose purity and belief in democracy was proof that even the most well-intentioned of individuals was not beyond being corrupted. The line (in the film) that directly proceeds the one cited above tells a tale: one about the presence of enemies at the Roman gates. As Dent narrates, democracy was suspended, thereafter, one man appointed by the people to protect the city, heeds that call, not as an act of valor or honor, but as a public service, a duty.

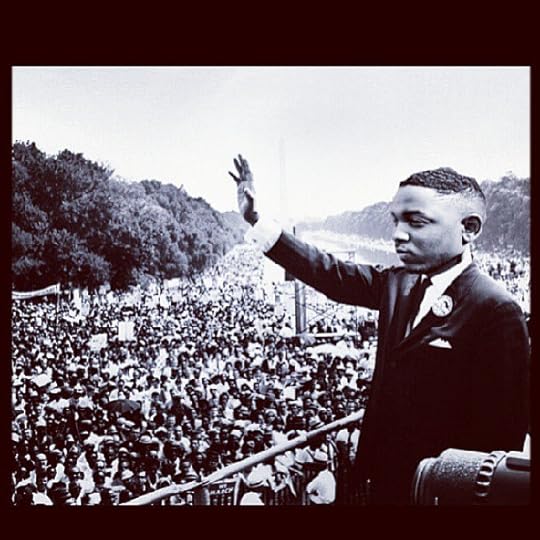

While Gotham City may just as well be the most famous city in the world, the city that birthed this thing called hip-hop, Harvey Dent is no Kendrick Lamar or Mayor Bloomberg, nor for that matter is Two-Face. It’s been over a week since Hot 97’s resident DJ, Funkmaster Flex debuted the song “Control” by Big Sean featuring Kendrick Lamar and Jay Electronica. The song lasting well over seven minutes, features some pretty sick lines that somehow got lost in the three-minute barrage that was Kendrick Lamar. A title wave of sorts, the verse took hip-hop to task for its lack of creativity and lyrical substance, short-lived lifestyles, fantasies, and images. In the process, Kendrick paid homage to his predecessors and peers, while being critical of the contemporary landscape of hip-hop culture at large.

While debates continue to swirl about those mentioned, implied, and flat out ignored, the likes of J Cole, Big Krit, Wale, Pusha T, Meek Mills, A$AP Rocky, Drake, Big Sean, Jay Electronica, Tyler the Creator, and Mac Miller, were mentioned by name. Since the outing of Lamar's fellow peers, a plethora of artists have countered with their answer via twitter, the blogsphere, and music outlets. Freestyles and reactions have staked their claims and place in hip-hop, while attempting to establish the artist’s lyrical prowess.

The responses read like a who’s who list in the hip-hop game with rejoinders coming from the likes of Joell Ortiz, B.O.B., Joe Budden, Meek Mills, Mac Miller, Iman Shumpert, Ransom, Astro, JR Writer, Lupe Fiasco, Cassidy, Jasiri X, Raekwon, Los, the Mad Rapper, Maino, and Papoose, amongst others, including Kevin Hart and Phil Jackson. The retorts hit a spectrum, from those that applauded Kendrick’s critique as something known to be true, yet gone unspoken, to the flat-out scorn that is deserving of a lyrical uppercut.

Kendrick’s verse, while overshadowing the responses of his peers, in some ways solidifies his rise to prominence as an MC more than capable of flexing some lyrical muscle. However, the verse and its subsequent comeback tracks should serve as a reminder that these intertextual exchanges in direct response to the sonic and poetic canvass(es) crafted by Kendrick are indicative of a much larger issue, an aural signaling of yet another anxious moment in hip-hop culture. To this effect we must ask ourselves as consumers and fans of the culture whether or not these symptomatic expressions of hip-hop’s anxiety are properly situated and contextualized.

Furthermore, do these claims, rooted in and through braggadocio and competition, take hip-hop in any particular direction? Are these responses merely manifestations of play, or are they significant disruptions in the hip-hop arena, more specifically within the stage that is the United States? In what ways do we process, analyze, and critically respond and where might the aftershock be found? Where does hip-hop go from here? What will the context of the next anxious ridden moment? Is there a performance of self and one’s artistic abilities in (mis)regognizing and (mis) reading Kendrick? What might we conclude and find from these questions? In what ways might Kendrick Lamar’s “Control” verse and others serve to reinscribe norms and expectations within hip-hop? These are precisely the kinds of questions that artists, fans, and consumers must answer.

This moment of anxiety, hip-hop’s anxiety is yet another iteration of Nas’ famous, if not controversial claim, announcing the death of hip-hop (side note: other artists such as GP Wu, Outkast, and Talib Kweli, amongst others made similar claims prior to Nas’ album). More broadly the dialogue across the coasts seems to have very little to do with name dropping or claiming allegiances to one’s home coast. The debate is hip-hop’s strawman put out for public show-and-tell, a critical lyrical dialogue about the commercialization of sounds, the pressures of conforming to that sound, how sounds become canonized, and the mass appeal of how sound travels, is imitated, disrupts, and goes ignored.

It is yet again, the anxiety of influence rearing its ugly head in the realm of popular culture, specifically hip-hop. These collective anxieties of influence, propel both fan and artist forward in generating excitement, while (un)intentionally harping back to a nostalgia that cultivates, reinforces, and ultimately fails at constructing a narrative of the authentic vis-à-vis the homage and the newest crop of artists. This unspoken, yet readily acknowledged nostalgia lies dormant in between rhymes as it exposes further arguments about the tangible and intangible qualities that separate hip-hop artists from rappers. A sequel to the Hip Hop is Dead aftermath, Kendrick’s verse is a clarion call to “carry on tradition,” proving still, that MCs are capable of throwing on the suit and mask in bearing the responsibility of being the Dark Knight when the occasion merits it.

***

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent researcher and scholar who can reached via Twitter at @BazookaGomez84 or via email atgomez.wilfredo@gmail.com

Published on August 25, 2013 04:49

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.