Why Chesterton Will Be a Saint

Why Chesterton Will Be a Saint | Dale Ahlquist | Catholic World Report

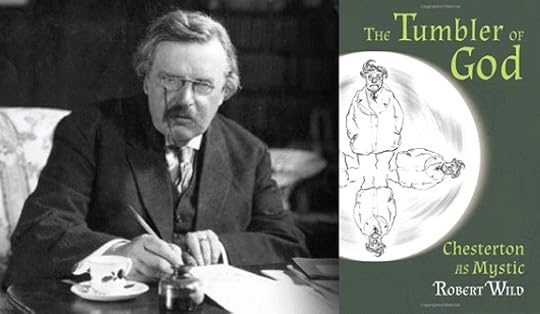

A review of Father Robert Wild’s The Tumbler of God: Chesterton as Mystic

Not every saint is a mystic. Not every mystic is a saint. And not every 300-pound, cigar-smoking journalist is both a saint and a mystic. But I’m quite sure at least one of them is. And I’m not alone in that opinion.

Father Wild’s book is especially well-timed. I was recently taken to task by a reviewer because I had suggested in my book The Complete Thinker that G.K. Chesterton is a mystic. And so it is convenient to have suddenly at my disposal an entire book written in defense of that one statement. But the book is well-timed for another reason. Father Wild not only argues quite convincingly that Chesterton is a mystic, but by the end of the book he also makes the case that Chesterton is a saint. Things appear to be heating up in that regard, too. And Father Wild is not just blowing holy smoke. He knows what the Church requires for sainthood. He is the postulator in the cause for Catherine de Houck Dougherty, who, incidentally, was also a mystic.

Like any good writer, including like Chesterton himself, Father Wild takes the trouble to define his terms. He surveys the work of the leading writers on mysticism and shows how they converge but also where they part ways. Mysticism has to do with a direct experience of the divine truth, an “acute awareness” not only of the Creator but of his creation. Certainly the mistake about mysticism is that we associate it with remoteness from the rest of us, a hermit in a cave, or a prophet on a mountain top. Mysticism may make a stop there, but it does not stay there. For almost every reason, Chesterton damages most of our preconceptions about mysticism, even going so far as to say that the common man is a mystic, because mysticism is sane. It grasps reality. It rejoices in the sunlight. It knows the balance and proportion of things, including the importance of important things and the unimportance of unimportant things. Or to put it in Chesterton’s own words (in a passage which unfortunately does not appear in the book):

The common man is a mystic. Mysticism is only a transcendent form of common sense. Mysticism and common sense alike consist in a sense of the dominance of certain truths and tendencies which cannot be formally demonstrated or even formally named. Mysticism and common sense are like appeals to realities that we all know to be real, but which have no place in argument except as postulates.

Chesterton tells us the things we already know, only we did not know that we knew them. The difference between him and us is that he is trying to give us the same vision he has, what Father Wild calls his “contagious happiness and inner peace…he was imbued with a kind of unpretentious beatitude that tended to convey itself to those around him.” He is trying to share his sense of wonder, his thankfulness, his joy. And the source of all these things is God.

Indeed, Robert Hugh Benson, whose too-short life and writing career just overlapped with Chesterton’s, perceived as early as 1905 that Chesterton was a mystic because of his joy, his confidence, and his common sense.

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers